In memoriam: Irving L. Peddrew III

Irving L. Peddrew III of Hampton, Virginia, who integrated Virginia Tech’s classrooms in 1953, passed away on May 11. He was 88.

While enrolled, Peddrew was forced to live and eat off campus. Decades later, he became a namesake of a residence hall that now houses over 200 students and a Black-culture-themed living-learning community.

Peddrew was the first Black student admitted to a historically white, four-year public institution in any of the 11 former states of the confederacy. He arrived in Blacksburg more than half-a-year before the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, and during his first year was the only African American among the university’s 3,322 students.

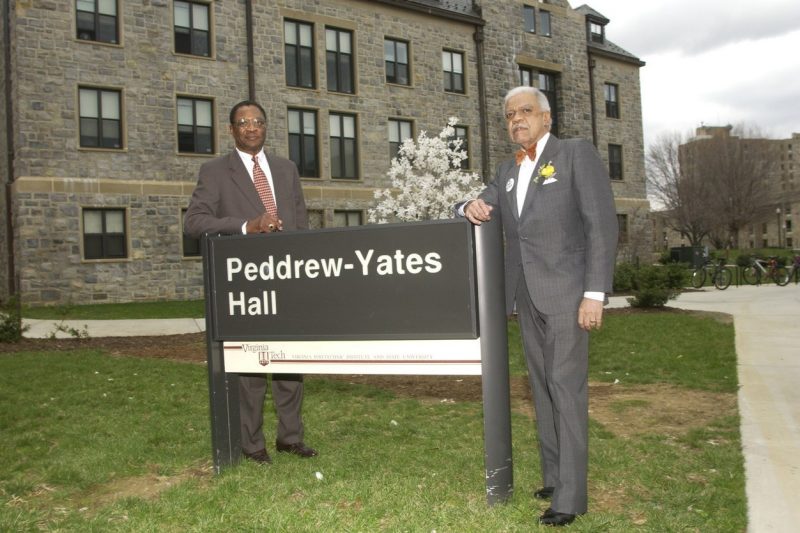

Although Peddrew chose to withdraw from the university before the start of his senior year, his academic performance and character impressed many, helping pave the way for other Black students, including three in 1954. In 2003, Virginia Tech named Peddrew-Yates Hall for him and Charlie L. Yates, who became the university’s first Black graduate in 1958.

In 2016, Peddrew became just the ninth person to receive an honorary degree from Virginia Tech. Virginia Tech President Tim Sands conferred a bachelor’s of engineering to Peddrew during that year’s University Commencement.

“Mr. Peddrew endured unfair and oppressive treatment with dignity and strength, hoping to make a difference for those who would follow him — and he did,” Sands said. “It was an honor to know him and present him with the Virginia Tech degree he earned. He will be remembered as a leader among those who laid the foundation for our growth as a diverse and inclusive institution.”

Ed Baine, rector of the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors, said Peddrew was an inspiring figure for generations of Hokies.

“It takes a special person to be a pioneer,” said Baine, a member of the Class of 1995. “I’m grateful to Irving Peddrew who opened the door for thousands of Black students who followed at Virginia Tech. As a student, he chose to leave after three years, but he came back to Virginia Tech, time-after-time, later in life, to help connect our community. He was a dear member of the Hokie family, and we extend our condolences to his family. We will all miss him."

Peddrew grew up in a family where education was a priority but expectations of acceptance in the Jim Crow South were tempered. Both his parents attended what is now Hampton University. Peddrew excelled academically at George P. Phenix High School, in Hampton. He played saxophone and clarinet, and was a member of the school’s marching and concert bands.

When Peddrew considered where to enroll in college he first leaned toward the University of Southern California. A teacher he admired encouraged him to apply to multiple schools in Virginia that had never admitted Black students.

He listened, and submitted several in-state applications. Only Virginia Tech said “yes,” but it came with a catch that Peddrew discovered after arriving in Blacksburg. He could not live on campus or eat in the dining facilities. He wound up lodging with a Black couple, Janie and William Hoge, at their home on Clay Street.

“I thought I would be a part of the student body all around,” Peddrew said in 2020. “I didn’t know about all the restrictions. But since I was there, I said, ‘Well, let’s make the best of it.’”

Across interviews conducted in 2002, 2020, and 2021, Peddrew described both pleasant and painful moments. He felt like part of a team during Corps of Cadets drills. Multiple classmates told him they would be happy to room with him, if allowed. Johnson Publications, which put out Ebony and Jet magazines, sent a photographer to campus to cover him.

Peddrew recalled Virginia Tech administrators telling him, “Because of my performance and the way I carried myself during my first year, my freshman year, they were convinced that it didn’t necessarily have to be a problem accepting more Black students.”

He also recalled the painful decision he made, under social pressure, not to attend the Ring Dance, an event that celebrates the transition from junior to senior year. Rumors swirled at the time that nearby women’s schools would not allow their students to attend the dance if Peddrew went. While the rumors proved unfounded, Peddrew ultimately decided not to go.

Around that time, through his involvement with the YMCA, Peddrew traveled to the West Coast as part of a project called Students in Vocation, met peers from all over the country, and decided not to return to Virginia Tech.

He continued his education at the University of Southern California and built a career in business, working out of San Francisco, then Los Angeles, in positions that allowed him to travel extensively.

Eventually, he returned to Virginia. He worked at Newport News Shipbuilding and at Hampton University before retiring in 1994.

When Peddrew reconnected with Virginia Tech later in life, he got a very different reception. Fifty years after his pioneering enrollment, more than 500 people attended the ceremony to dedicate Peddrew-Yates Hall, the university’s first building named for African Americans.

“Back then, I wasn’t even allowed to live on campus,” Peddrew said at the ceremony. “So while this is an ironic honor, it is still a great honor and one that my family and I will cherish.”

After moving back to Hampton, Peddrew became close friends with Jim Watkins ’71, a dentist who also lives in that city. Watkins has been involved in Virginia Tech’s Black Alumni Reunion program since its inception, is on the board of the Virginia Tech Black Alumni Society, and often accompanied Peddrew to university events. One such event was the 2016 University Commencement, when Peddrew received his honorary degree.

“I know he appreciated that,” Watkins said. “He was really beaming. I won’t say it felt as good for him as it would have had he gotten it at age 21, but I know he appreciated it. I, as a Black alum, appreciated it. I felt closer to Virginia Tech that day than I did at my own graduation — more than I ever have, except maybe at my grandson’s graduation from Virginia Tech in 2021.”

In 2017, a year after receiving his honorary degree, Peddrew returned to campus to give the keynote address at a conference for students, faculty, and staff hosted by the Virginia Tech Black Male Excellence Network.

“It was almost a full-circle moment,” recalled graduate degree alumnus Tommy Amal ’14, who helped coordinate the event while working for the university’s Student Success Center. “We had all these participants, young Black men, many in the Corps of Cadets or who were actually living in Peddrew-Yates Hall at the time, and were able to see their lives reflected in his story. It’s a tremendous story.”

In another full-circle moment Peddrew, who felt so unwelcome at the 1956 Ring Dance that he skipped it, was chosen by the Class of 2023 to be its ring namesake.

“I wasn’t fully a student,” Peddrew said when the honor was announced. “I wasn’t fully accepted, and now I am. I am. I really feel part of the university, and I can say, ‘That I May Serve.’”

%20Lee%20Header.png.transform/m-medium/image.png)