Researchers are pulling movements out of microfilm with digital history

Firsthand accounts and images of Black soldiers hold hidden chapters of U.S. history. Historians and computer scientists are harnessing technologies like virtual reality and AI to equip the public to immerse themselves in those perspectives, learn from them, and broaden historical dialogue.

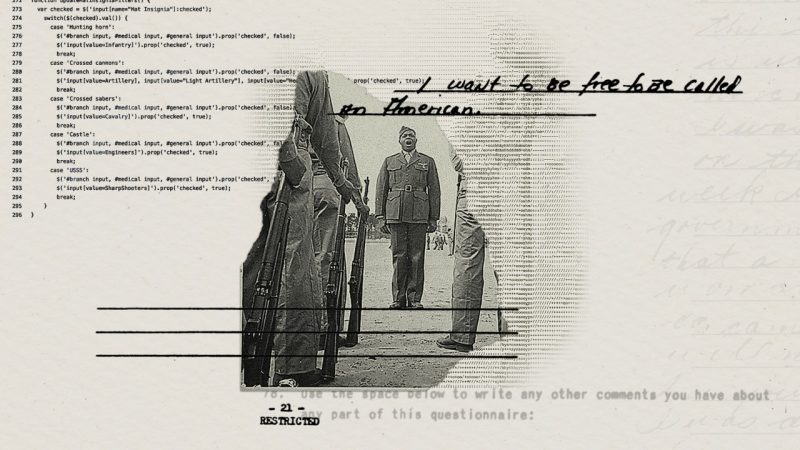

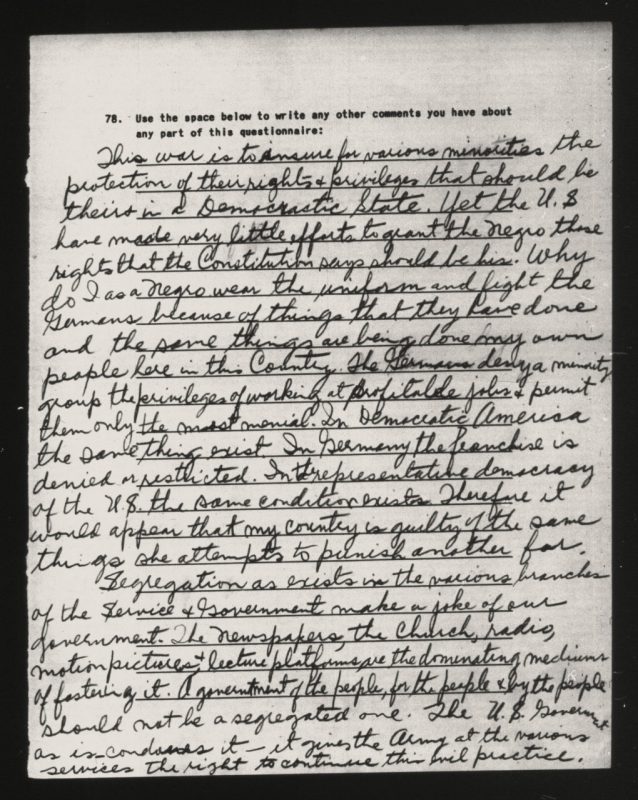

Question 78: Use the space below to write any other comments you have about any part of this questionnaire.

“The Germans deny a minority group the privileges of working at profitable jobs & permit them only the most menial,” one surveyed soldier in the segregated U.S. Army wrote in 1943. “In Democratic America the same thing exist. In Germany the franchise is denied or restricted. In the representative democracy of the U.S. the same conditions exists. Therefore it would appear that my country is guilty of the same things she attempts to punish another for … A government of the people, for the people by the people should not be a segregated one.”

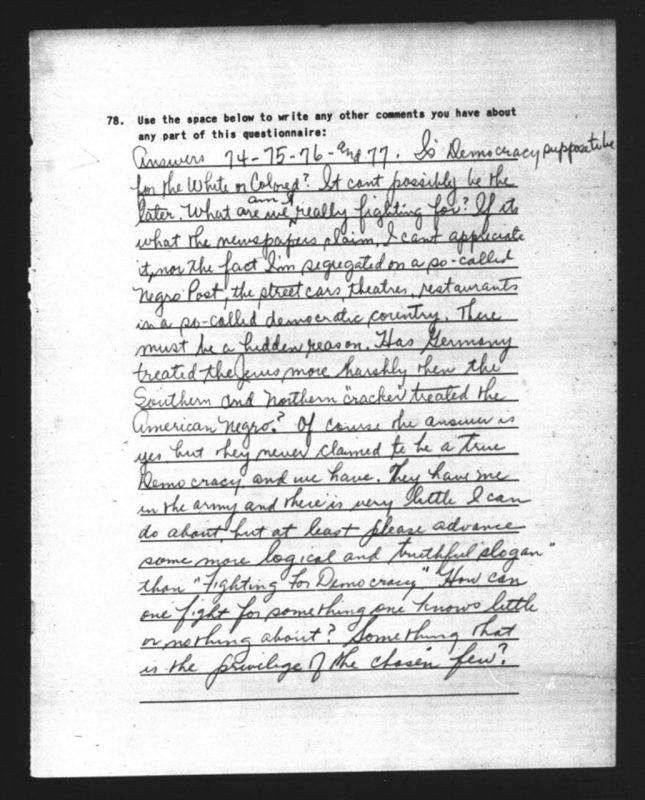

Four years into World War II, 7,434 Black soldiers from 60 domestic units sat down to Survey 32. It was one of over 200 surveys administered by social and behavioral scientists assigned to gather feedback on morale and the efficiency of the Army, for the organization’s research branch. But Survey 32 was focused primarily on race relations.

The soldiers anonymously ticked boxes and gave short-answer responses to its questions: Did the soldier feel he would have better or worse job prospects after the war? Did he foresee having more rights and privileges, or less? Did he feel he had a fair chance to support the U.S. in winning the war?

The final question, No. 78, was the only free-response prompt of Survey 32. Soldiers could use the full, ruled page to discuss anything the survey had covered. Thousands of surveyed soldiers answered, and spilling into the margins were words of anger, anguish, hope, resignation, resolve, and recounting of mistreatment of Black soldiers stationed in U.S. towns, as they rode segregated buses, sat in segregated theaters, and served in segregated units.

Eventually, the responses to No. 78 and the survey’s additional data ended up in microfilm rolls and ASCII text files at the National Archives. When history professor Ed Gitre came across the microfilm and its contents in 2009, he felt that his students and members of the general public needed to be able to see each of the responses for themselves. He began a project to transcribe and bring online a total of 65,000 pages touching on the topics of Survey 32, plus dozens of other subjects that to him expose the very human sides of the American soldier in World War II. “The ability to get these individual stories out and to preserve them, and to make them accessible to as broad of a public as possible, I think is what drives me ultimately,” Gitre said.

At Virginia Tech, historians and computer scientists are working together to enable that kind of broad public access to history using tools like immersive visualization, artificial intelligence, and crowdsourcing. They've applied these technologies to tasks like sifting through piles of documents and making sense of them or leafing through countless pages of reference books for an image — tasks that in traditional modes of study can overwhelm inquiring minds. The aim is to create technology-enhanced experiences for human users, putting them in control of platforms that make historical study more approachable and interactive.

“These researchers represent what is especially critical today: civic-minded, human-centered approaches to technology,” said Sylvester Johnson, executive director of the Tech for Humanity initiative and a humanities scholar who studies technology, race, religion, and national security. Gitre and others working in digital history at Virginia Tech serve as Tech for Humanity scholars.

“Their projects, which leverage digital technology to generate a positive social impact, exemplify the larger aims of our universitywide Tech for Humanity initiative,” Johnson said. “It’s now clear that the most difficult problems we will need to solve are at the human frontier. That is exactly why it’s exciting to see the scholars advancing this direction in research and public impact.”

Space to think

At the Moss Arts Center, 17 history students took turns moving through the open space of the Sandbox, wearing virtual reality goggles and wielding hand-held controllers. Inside Immersive Space to Think, a 3D virtual workspace system, the students could face a display wall, walk its length, pull up documents, move them, and cluster them in space as they studied the contents.

The documents loaded into the system at the moment contained transcribed responses to Survey 32. After asking the National Archives to digitize 44 microfilm rolls containing the survey data, Gitre had recruited students in his undergraduate World War II history course and more than 7,000 volunteers crowdsourced on Zooniverse to transcribe each of the responses four times.

They received an AI boost from computer scientist Kurt Luther, whose Crowd Intelligence Lab contributed Incite, an open-sourced software transcription plug-in they developed for another U.S. history crowdsourcing project led by Paul Quigley, the James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor in Civil War Studies.

As transcription went on, Gitre wanted to give his students immersive ways to work with the data set. He learned from Luther that other researchers were creating a virtual workspace for document sensemaking at the Center for Human-Computer Interaction, led by Doug Bowman, the center’s director and the Frank J. Maher Professor of Computer Science. In 2019, Gitre and Bowman saw an opportunity for symbiosis between their two projects: Gitre’s students could work in the system, Immersive Space to Think, and take advantage of its features as they studied survey responses, while Bowman’s team could learn from their use of the workspace.

Bowman sees historical inquiry as a natural fit for a type of study to inform the development of Immersive Space to Think. Historians wrestle with overwhelming amounts of document-based information from myriad sources and sift through them with attention to detail. The system could allow them to streamline what can be a physically and cognitively exhausting pursuit, he said.

“We’re replicating what someone might do with a whiteboard,” Bowman said. “But with virtual reality, we can enhance that interaction to make it more powerful and expressive.”

Soon, the system itself will learn from the students to support their sensemaking experience, in efforts led by Chris North, a professor of computer science and the associate director of the Sanghani Center for Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics.

As users cluster documents, pull them in closer or push them away, and look between them, the system will track their behavior — rapid gaze, for instance, could signal information overload, while certain clusters could indicate content priorities. That data will inform a machine learning algorithm that can identify clusters and suggest relevant documents to the user. “We’re not getting in the user’s way, but can give them really helpful shortcuts so that they don't have to do everything manually, in terms of searching, reading, and organizing,” Bowman said.

As Gitre works to make the full collection of survey responses accessible online in a website launching this summer, he plans to work with Bowman’s team to bring the experience of reading Survey 32 responses in Immersive Space to Think to members of the general public. This year, they received funding from the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology to design a World War II museum exhibit that will enable museumgoers to enter the virtual system and read the survey responses, while also viewing artifacts like service badges, medical kits, and photos.

Encounters with the firsthand soldier accounts could reveal for readers the sentiments that were building among Black soldiers in a galvanizing moment for activism, Gitre said. “The soldiers’ experiences really propelled the civil rights movement, precisely because of the fact that you had a military that had its army fighting fascism and authoritarianism abroad, while maintaining segregation and racial discrimination,” he said. “I want to bring these thousands of voices into that history, and wrestle with the idea of what makes a movement. We’re trying to learn the story of many thousands of African Americans who spoke up about Jim Crow and segregation.”

The first 209

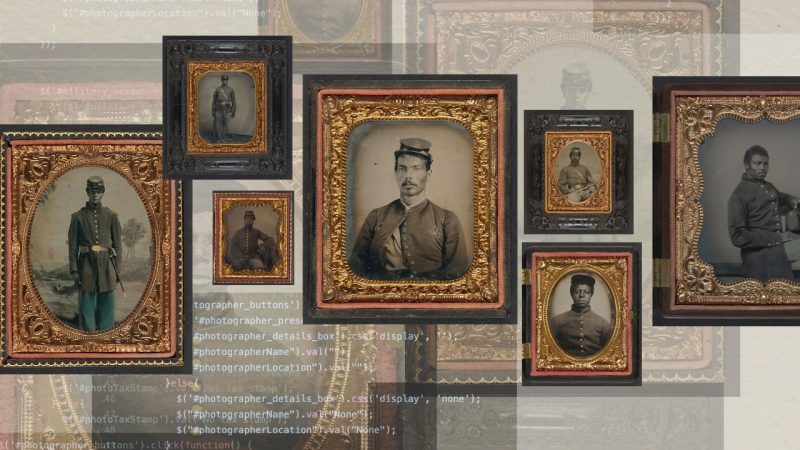

The soldiers sit for the portraits with their hands in their laps and their fingers interlocked. They stand with their arms folded or resting at their sides, or holding their bayonets with the sharp end up. There is Abraham, Charles, and Louis. Solomon, Octavius, and Wilson. They’re the subjects of 209 photos, representing a handful of the Civil War’s nearly 200,000 Black soldiers.

The images were tracked down by Natalie Robinson in 2018, when she was a history student at the University of Georgia and worked as an intern with the Crowd Intelligence Lab led by Kurt Luther, an associate professor of computer science at Virginia Tech and a faculty affiliate of the Department of History. That summer, Luther had tasked Robinson with combing museum and library collections, online government archives, and his own copies of reference books for images of Black Civil War soldiers and civilians to add to the Civil War Photo Sleuth database.

Civil War Photo Sleuth is an online platform that uses crowdsourcing and a combination of human and artificial intelligence to identify unknown soldiers and civilians in Civil War-era portraits. The platform allows users to upload photos and tag them with metadata such as photo inscriptions and formats, as well as visual clues like military rank insignia and uniform color. Users then try to connect the photos to identified soldier profiles, with military records attached.

The platform relies on its 15,000-plus users to help build the database. Before launching the site, Luther’s team pulled in nearly 20,000 photos from sources like the U.S. Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the U.S. Army Military History Institute to seed the site with identified reference images. The more users contribute to the platform’s store of images, Luther explained, the closer Photo Sleuth members can get to finding matches for their uploads.

As users upload photos and try to find a match, Photo Sleuth enables them to narrow down the possible matches among the database’s identified photos with the platform’s search filters, which are based on the visual clues tagged to each photo during upload. The platform then uses facial recognition to further whittle the selection down. In the last leg, it’s up to the user to look for a match. If users find one, they can propose it and indicate their confidence in it.

Luther said he’s been driven to create and improve upon Photo Sleuth by the role photos can play in our understanding of the past. “There's incredible visual power in these images,” he said. “They make the history come alive, they make it feel much more real — seeing the details of a person's face, the clothing that they're wearing, the equipment that they have with them.”

Photographic windows into the past of Black soldiers and civilians from the Civil War era, however, have always been difficult to find, Luther said. That disparity, one that reflects a wider pattern of erasure, exclusion, and destruction of records of Black U.S. history, was the reason for Robinson’s work trolling more collections for photos to add to the database as reference images. She remembers seeing signs of it during her search for identified images. Robinson kept running into the same photos as she went from one collection to the next. Early on, most of the photos the team had found to build the database were of white Union soldiers.

“There was a huge number of African American soldiers in the Union Army,” Luther said. “They were really instrumental to winning the war, some of them received medals of honor, but few of those photos survive today. You have Black soldiers composing 10 percent of the Union Army by the end of the Civil War, and on the other hand, it’s hard to find 100 identified photos today.”

Challenges on the technological side, in the field of artificial intelligence, have also shaped the team’s work. They use licensed facial recognition technology to support users’ sleuthing, but they avoid using a fully automated system to make the ID, Luther explained, because facial recognition alone is imperfect at identifying faces. It’s even been proven to fall prey to racial and gender bias, performing worse for people of color and women — and requiring many companies licensing out the technologies to revisit the inclusivity of the data used to train their algorithms.

That’s why it’s important not to lean too heavily on these licensed technologies, Luther said, and to instead allow human users to ultimately try to identify images — as genealogists, collectors, and family members tracking down their ancestors have long done in traditional photo sleuthing. “Facial recognition’s real strength is narrowing down possibilities,” he said. “It's not very good at comparing two photographs and telling you if it's the same person or not. Humans are much better at that. They’re able to look at all these details and think about the broader context.”

Robinson’s additions to the Photo Sleuth database have made it one of the largest collections of photos of Black Civil War soldiers found online. But the project was just a start, Luther said. He believes there are more images out there, in yet untapped contributions that he hopes Photo Sleuth users will continue to upload. “These users are bringing in photos from sources we would never have known about,” Luther said. “They’re coming from their attics, from their basements.”

As a home for these finds, Photo Sleuth has enabled users to go after projects they once figured as impossible, Luther said. “There are investigations happening that wouldn't have happened at all in the past,” he said. “The platform has allowed people to explore investigative threads that otherwise seemed too overwhelming to pursue. Suddenly, now they’re not.”