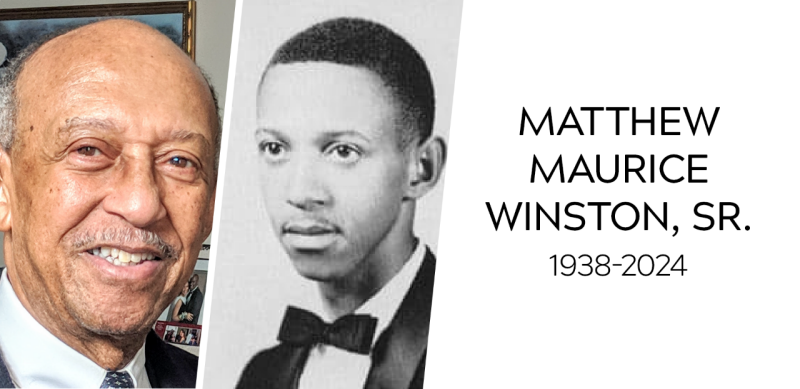

In memoriam: Matthew Maurice Winston Sr. '59

Photos courtesy of Matthew Winston, Jr.

Matthew Maurice Winston, one of the first Black students to attend Virginia Tech and the second Black student to graduate, passed away on May 14.

A Norfolk, Virginia, native, Winston graduated as his class valedictorian from Booker T. Washington High School in 1955. He enrolled at Virginia Tech, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering in 1959. Winston later earned a master’s degree in engineering administration from George Washington University.

Winston retired in 1994 after 35-years as an engineer, researcher, and administrator at NASA-Langley. He was recognized with many agency awards including a medal for his contributions to equal opportunity employment and a special recognition award for service to and management of NASA’s High-Speed Research team. Winston was also recognized with Booker T. Washington High School’s Distinguished Alumni Award.

Winston’s family and friends will remember his sense of humor, his love of jazz, and his ability to make friends wherever he traveled.

“Let us remember the joy he brought into the world and the kindness he showed to all,” Winston’s family wrote in his obituary. “May his legacy inspire us to live with the same passion, compassion, and integrity that defined his remarkable life.”

Winston’s legacy and voice lives on at Virginia Tech. In 1991, Winston and his son, Matthew Winston Jr. ’90, dedicated the mural entitled “Legacy” that sits outside of the Black Cultural Center in Squires Student Center. His story also has a place in University Library’s oral history archives. Ren Harman, oral history project archivist, sat down with Winston in February 2018 to talk about his early life, his time at the university, and his career after graduation.

“It [Virginia Tech] wasn’t nearly as big as it is now,” Winston Sr. told Harman. “It was only like 5,000 students when I started at Tech, and about half of them were GIs who were back from the Korean War.”

Winston remembered those soldiers being more mature and those just out of high school making up a second group, dividing the student body into what felt like two societies: adults with families and kids celebrating new freedom. All students were members of the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets with obligations that took up most of their time.

While Black students could enroll, they could not live on campus. Living off campus meant a 20-minute walk to and from the home of William and Janie Hoge, the Blacksburg family that housed the early group of Black students. Winston said he felt that not living on campus with the other cadets kept him from experiencing many pranks that all cadets at that time dealt with during their first year.

“Most of it happened after class or outside of the class, but there was enough of it that I learned something that served me well throughout my life, and that was how to take a lot of crap,” Winston told Harman.

Living in Blacksburg, Winston said the minority population was very small and his experience was isolating, but the Black community, especially those tied to the Christiansburg Institute, informally adopted and supported him throughout his education. Friends he made at Virginia Tech remained part of his life after graduation.

“After I had graduated and went to work, I ran into a lot of these people because they also worked at NASA,” Winston told Harman. “That was always a helpful situation to me…there were Tech guys coming out of the woodwork, and a lot of them had been there for a while.”

Winston said his experience as a student was difficult. When asked what he first thought of when someone says the words "Virginia Tech," Winston told Harman, “Now it’s pride.

“When I bring it all together about the experience, the early experience, the later experience, and then what it got me, it’s pride,” Winston told Harman. “It makes me proud to be a Hokie.”