Optimizing electric vehicles

Virginia Tech researcher Feng Lin is working to develop technology to strengthen the domestic supply chain for advanced batteries that power electric vehicles.

Feng Lin sees a strong connection between batteries and people.

“Not a single person is perfect, and that is the beauty of human imperfection,” Lin said. “Batteries are the same, every battery has its own flaws. You chose the one that does the best job for you and you live with its flaws. Of course, you ought to understand its flaws better, so they don’t bother you.”

And in both cases, finding a match is often simply a matter of chemistry.

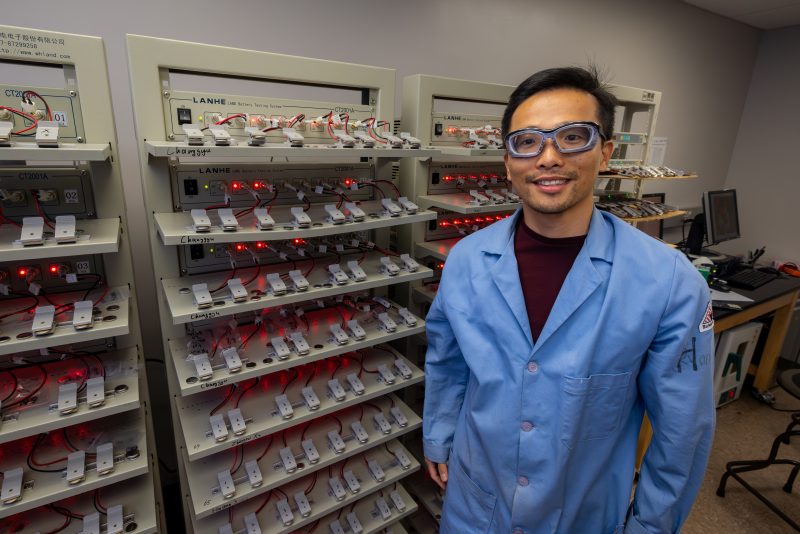

An associate professor in Virginia Tech’s Department of Chemistry, Lin’s work is focused on finding the best combination of materials and chemistries to create more efficient, affordable, and environmentally friendly batteries, especially when it comes to electric vehicles. Inside the Lin Lab, a person would find upwards of 600 different battery cells being tested for multiple uses and in extreme weather on any given day of the year.

“Some of them run for a year or longer, some two months in terms of cycles,” said Lin, the Leo and Melva Harris Faculty Fellow in the College of Science. “We have tested some batteries for tens of thousands of cycles. If you spread that out to real use, that’s decades of use.

During the past five years, this work has drawn the support of both government and industry, including grants from the Department of Energy (DOE), National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Office of Naval Research.

In January, the Lin Lab was awarded a $2.9 million DOE Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy grant to explore cobalt and nickel free batteries, especially for fast charging and cold weather.

And about nine months later, the DOE announced even more support, dedicating $3.4 million to the combination of Virginia Tech, General Motors, American Lithium Energy, Xpertography, and Fermi Energy, a Blacksburg-based startup Lin co-founded with a recent Virginia Tech graduate and former postdoctoral associate, Ray Xu. The new funding will allow the team to develop low-carbon footprint, chemistry-agnostic cathode materials manufacturing technologies. F. Marc Michel, associate professor of nanoscience and geoscience, and Sean McGinnis, as associate professor of practice and director of Virginia Tech’s Green Energy Program, are also key partners in this project.

Lin’s work comes at a time of critical and increasing need for all around better batteries. Electric vehicle sales topped 300,000 from July to September this year, putting the year-end sales on track to reach one million for the first time, according to a report by Cox Automotive.

Lin said it was such opportunities to impact the lives of others that drew him to batteries in the first place.

“Other projects I was involved with didn’t have that near-term impact while batteries impact aspects of almost everyone’s lives, and ultimately, can add to the global effort to combat climate change,” Lin said.

600+

batteries being tested inside the Lin lab for multiple uses in extreme weather

30%

the amount of battery life lost through improper charging

$6.3m

the amount of total funding awarded to explore cobalt and nickle-free batteries and develop low carbon footprint technologies

Sandwich stuff

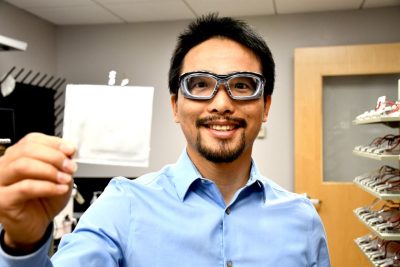

When describing the basics of batteries, Lin often shifts the analogy from relationships to bread and deli meat.

He describes batteries as similar to sandwiches in that they have two ends — the cathode, the positive electrode, and anode, the negative electrode — and have lithium-ion electrolytes working hard in the middle.

“You can think of that as whatever meat or type of sandwich you want to have,” Lin said. “Well, the reality is what you put in between the positive and negative electrodes could greatly impact the safety of your batteries.”

Recently, Lin further broke down battery functions in a column for The Roanoke Times:

“A battery charges when lithium ions and electrons are moved from the positive electrode to the negative electrode. The battery discharges when the opposite happens. At its best, all of these ions and electrons make the round trip.”

Part of the challenge with current batteries is that materials used for most cathodes and anodes include minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and graphite, which are costly and difficult to obtain. Cobalt can be especially troubling because deposits are most available in a handful of countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which has questionable work practices at best.

This challenge is multiplied by the manufacturing process, which typically requires using a large amount of electricity and water, and results in sizable emissions.

“Not every single electric vehicle coming out is clean and green from day one,” Lin said. “It usually takes them tens of thousands of miles before they can compensate for the environmental impact that was created due to manufacturing of the battery.”

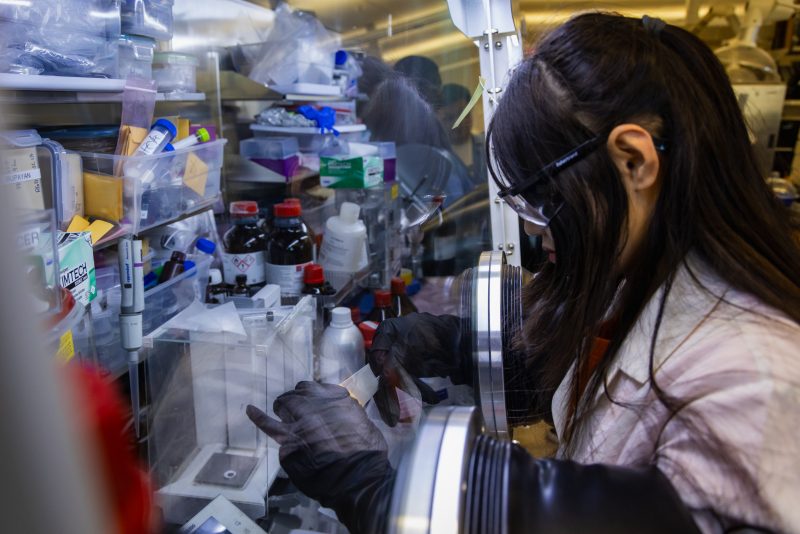

Lin’s lab is working to find alternative materials and develop an alternative manufacturing process that is kinder to the environment, as well as the user’s wallet and overall experience.

A better battery for all conditions

Charging an electric vehicle takes much longer than adding gasoline to a combustion engine car and battery performance can be greatly impacted by hot and cold weather.

The DOE has charged Lin and his team with finding solutions to these challenges. According to the DOE press release about the $2.9 million grant, the Virginia Tech team will use “will develop fundamentally disruptive electric vehicle (EV) batteries that combine cobalt- and nickel-free cathodes, electrolytes that enable fast-charging and all-weather operation.”

As part of the project, the team will incorporate coal-derived carbon materials into advanced silicon anodes. Lin said his lab is working to identify the ideal carbon properties for this particular use. Then they will develop a process to transform coal to provide these properties.

“Fast-charging and low-temperature performance remain significant technical challenges in current battery technologies,” said Lei Tao, a research scientist in the Lin Lab. “Our group has recently developed some solutions, including redesigning battery materials and electrolyte compositions, to successfully achieve fast-charging and low-temperature performance of the battery.”

Tao’s background is in forestry engineering, but after a postdoctoral fellowship at Virginia Tech, he is now leading the Lin Lab’s effort related to faster-charging and more extreme condition durable batteries.

“Our research has become very interdisciplinary, where we need chemistry, materials science, and engineering to come together,” said Lin, who is also a member of Virginia Tech’s Macromolecules Innovation Institute and an affiliated faculty member of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

“If we can figure out how to combine all those great things in one battery, that would be making a tremendous contribution,” Lin said.

Once the lab finds workable solutions, it will work with its industry partners to scale it up for commercial use. One of those partners is Fermi Energy, which was founded in 2022 with the help of Virginia Tech’s Innovation and Partnerships team.

“The idea is that we develop something and make the materials at a smaller quantity then they [private companies] will help us scale it up to the very large quantity so we can make larger size batteries to be tested and validated,” Lin said.

Charging up the battery workforce

While the Lin Lab’s goal is the development of better batteries, it’s also focused on developing the talent needed to continue and expand this work into the future.

“For me, this is in a weird way the fulfillment of my childhood goal to solve climate change,” said Katelyn Meyer, a graduate student studying chemistry.

Meyer is one of more than a combined two dozen graduate and undergraduate researchers working in the Lin Lab. She said the practical applications of the concepts they work on are extremely motivating and she believes the experience will accelerate her own career as a researcher.

“I know this will give me the ability to go forward with the tools to not only accurately characterize problems that are happening, but to also actively work to find solutions to those things,” Meyer said.

Afolabi Olayiwola, who is also a graduate student studying chemistry, said he sees the lab’s research is similar to the cycle of existence and growth.

“We make new battery materials from the particle level to the industrial scale after several developmental stages,” Olayiwola said.

Olayiwola’s work focuses on developing anode materials and exploring the possibility of coal-based alternatives.

“Like making lemonade out of lemons, coal can be a pathway to clean energy via conversion to a battery material, Olayiwola said.

Along with helping grow the future workforce, Lin said including a wide diversity of ages, genders, and backgrounds in the scientific processes also serves to enhance the research itself.

“If you bring all these different people together then somehow, great ideas tend to happen,” he said. “Being around great people is really the key, and in a lab like mine, everyone is motivated to make a positive change. Over time, they become better than me.”

And Lin is careful to always remind the student researchers that they may never know the true size of the positive ripple from their hard work.

Feng Lin

Associate professor

Learn more about the research.

Feng Lin is a chemistry professor in the College of Science His research focuses on EV batteries with a goal to to create batteries that are both cost effective and can hold a charge over thousands of power cycles.

Virginia Tech offers a full range of ways to engage. Let's build a comprehensive relationship that helps your company meet its strategic goals.

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)