For Marc Lewis, graduation is more than a degree

“Whether it’s the unimaginable stress of his upbringing, his heroic service to our country in the U.S. Army, or his steadfast determination to get a college degree, Marc has deservedly earned the respect of our players, coaches, and staff," said Virginia Tech Head Football Coach Justin Fuente

“I’m getting my Ph.D. 45 minutes from where I was homeless and from where I was abandoned as a baby in a trailer,” Marc Lewis said. “It’s surreal to be able to do this.”

Editor’s note: This story has been modified and condensed from the original version.

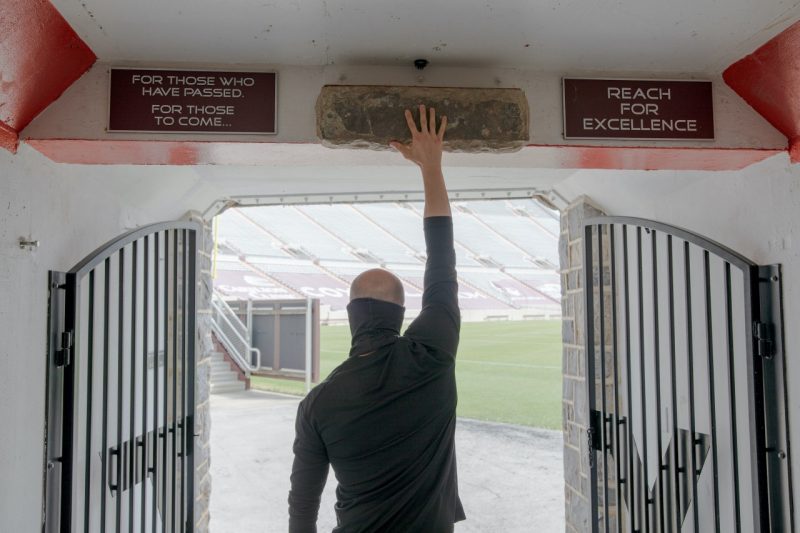

Marc Lewis heard "Enter Sandman" blare and felt Lane Stadium shake. Maroon- and orange-clad football players surrounded the Virginia Tech director of sports science in the moments before the team rushed onto the field.

It was at this moment when Lewis knew he had come full circle. He thought back on his childhood, his challenges in foster care, and being homeless in nearby Roanoke, Virginia. How he served in the U.S. Army in Iraq. How before all of that his grandfather took him to the Virginia Tech football game in which Michael Vick made the ridiculous flip into the endzone against James Madison 20 years earlier.

This was a moment, one of just a handful that a person has in a lifetime, that puts everything into perspective.

“I just couldn’t believe that I was there based on where I was and I couldn’t believe this was real,” Lewis said of the memory of running out of the Lane Stadium tunnel. “I put one foot in front of the other for a very long time to get to that moment.”

On May 15, when Lewis earns his Ph.D. from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences’ Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise, that next moment arrives.

“Just because we may be in a difficult position with how we’re raised or what we experience doesn’t determine where we can end up,” Lewis said. “You can achieve a lot by just being persistent over a long time.”

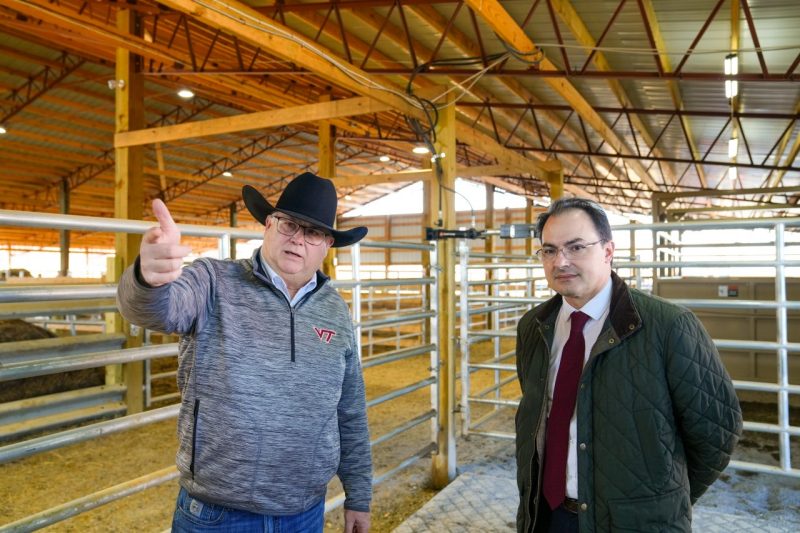

Lewis implemented GPS training monitoring with the Virginia Tech football team, helping players reach their full athletic potential.

Perseverance

Lewis was born in Bluefield, West Virginia, and entered the foster care system at a young age and was in and out of homes throughout his childhood.

As a teenager, he got an under-the-table job at a construction job and a local fast-food restaurant. Lewis saved up some money and, at the advice of a boss, was advised to become an emancipated minor. This opened him up to state assistance as a minor as Lewis would be considered an adult.

Some time went by and Lewis wanted to get some kind of education and started going to an adult education center in Bluefield that would help him study for his GED, as his last formal education was a month of ninth grade. He walked back and forth and caught the eye of a military recruiter.

This piqued Lewis’ interest.

“I thought it was a way out and it seemed almost too good to be true,” he said. “You sign up and get a paycheck? I know it wasn’t much, but to me, I had no idea what to do with all the money. Plus, they paid for my GED.”

Lewis hadn’t been taking classes for long, but the military wanted him to take the GED anyway to see how much more studying he had to do before passing.

Lewis passed on the first try, just weeks after taking classes at the adult education center.

Earning his GED opened the door to the military, which, in turn, would open the door to collegiate courses.

Lewis started in the infantry, excelled in boot camp, and was promoted to airborne infantry in short order.

The entire reason Lewis joined the military was to get a college degree and when he returned to the United States after serving his country, he made that his top priority.

Near the end of his time in the military, he got into physical conditioning and physical training. It came naturally and was how he differentiated himself in the military.

An old squad leader had briefly gone to college to major in exercise science and lent some old textbooks to Lewis.

“I thought ‘you can go to school for this? This is amazing!” Lewis said. He knew he was hooked.

He took remedial courses at West Virginia University to build a foundational education to make up for not having a formal high school experience.

After admittance to the exercise physiology program at West Virginia University, Lewis soaked up everything he could. One of the professors, Jean McCrory, noticed Lewis and his continual effort to learn. She recommended that he transfer to another university to get more hands-on research as an undergraduate.

Based on his transcripts, she told Lewis he could go anywhere. He applied to the University of North Carolina, Wake Forest University, and the University of Virginia. He was admitted to all of the schools and got scholarships to each one. Lewis accepted a full academic ride to Wake Forest.

“You can imagine that a tattooed 20 something-year-old, as an undergrad at Wake Forest, a traditional school and a great school, and you're going to class with like people that are 17 and graduated early. It was an interesting dichotomy,” Lewis said. “I got to experience what I wanted which was to be an undergraduate engulfed in research.”

In addition to the research, Lewis worked with Wake Forest’s strength and condition coach for the women’s soccer team and did personal training outside of his other responsibilities to keep one foot in research and one in application. Lewis graduated in 2014.

His desire to continue his education didn’t stop, and he earned his master’s from the University of South Carolina to bring full-time sports scientists to collegiate and professional sports.

"I’d suggest that perhaps no one else currently associated with Virginia Tech football has overcome bigger odds in life to achieve what Marc Lewis has done,” said Virginia Tech Head Football Coach Justin Fuente.

Coming full circle

When Lewis’ biological grandmother was diagnosed with colon cancer, it changed everything.

“She had no money, nothing,” Lewis said. “I decided to come to Virginia Tech to pursue my Ph.D. to be close to her.”

Before he started his Ph.D., Lewis earned two master’s degrees, one in public health and another in higher education at Virginia Tech. It took a little time, and Lewis got his mentor and into the program.

"Marc sets a high bar for himself and doesn’t let obstacles distract him from his goals. He is a highly motivated individual focused on generating high-quality work," said Kevin Davy, a professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise and Lewis' Ph.D. mentor. "It has been a privilege to work with Dr. Lewis at Virginia Tech and to see the impact he’s had in the classroom and on the athletic field."

Lewis interned with Greg Werner and the Virginia Tech women’s basketball team, which in turn introduced him to the Virginia Tech football team.

“Grit and perseverance are two of the qualities we emphasize frequently in our football program. There’s no shortage of guys on our team who have rebounded from injuries, hardships, or other obstacles to enjoy success on the football field. However, I’d suggest that perhaps no one else currently associated with Virginia Tech Football has overcome bigger odds in life to achieve what Marc Lewis has done,” said Virginia Tech head Football Coach Justin Fuente.

“Marc is an incredibly valuable member of our team who incorporates science and technology to maximize the potential of our student-athletes,” Coach Fuente continued. “But even more importantly, Marc serves as a real-life example of someone who embodies the traits we value the most as a football team. Whether it’s the unimaginable stress of upbringing, his heroic service to our country in the U.S. Army, or his steadfast determination to get a college degree, Marc has deservedly earned the respect of our players, coaches, and staff. He’s a remarkable man with a remarkable story. I’m extremely grateful to have someone who possesses his talent and character working with our young men on a daily basis.”

The team had just gotten some new GPS training equipment, which allows detailed information about practice performance to be viewed and analyzed by coaches.

Lewis focused his dissertation on this same topic – athlete monitoring in American collegiate football.

Lewis implemented this monitoring with the football team, helping players reach their full athletic potential. Equipped with a GPS monitoring device and heart rate monitor, he’s able to download a set of 125 variables for each player after practice.

As the assistant director of strength and conditioning and director of sports science, Lewis narrows those variables down to a handful of important ones that can be tracked daily.

This not only helps the players reach their on-field potential, but also helps them safely return from an injury, prevent injuries, and helped with the return to play COVID-19 protocols in 2020.

“We can use technology and make it a part of how we do things,” Lewis said. “We can take the data and use it intelligently while being tough on the field.”

While he loves working in college athletics, he couldn’t work with another school’s football team after working with the Hokies. He turned down the head applied sport scientist position for the University of Texas football team.

After earning his Ph.D. from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Lewis will become a tenure-track professor at Valdosta State University in Georgia.

“I’m getting my Ph.D. 45 minutes from where I was homeless and from where I was abandoned as a baby in a trailer,” Lewis said. “It’s surreal to be able to do this.”

— Photos and story by Max Esterhuizen