‘The Land Speaks’ exhibit transformed into virtual experience

The pandemic has forced museums around the world to temporarily close the doors to their exhibits. In keeping with other creative adjustments, the University Libraries pivoted to hosting online exhibitions in place of physical ones.

After the initial design planning stage of a recent exhibit, The Land Speaks: The Monacan Nation and Politics of Memory, Scott Fralin, exhibits program manager and learning environments librarian, was ready to construct the exhibit physically by hand. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. Ralph Northam’s statewide stay-at-home directive, and the university’s transition to essential operations.

On a normal day at Newman Library, Fralin can be found tinkering. With a yellow number-two pencil tucked behind one ear, sleeves rolled up, and a cup of strong coffee in hand, Fralin is the man behind the extraordinary exhibits at the University Libraries.

Fralin has an office that is often the envy of many. Strategically organized yet creatively messy, this maker-space holds treasures, from tools, to spare parts, to prototypes, to playful contraptions — ingredients that build the University Libraries’ unique exhibits.

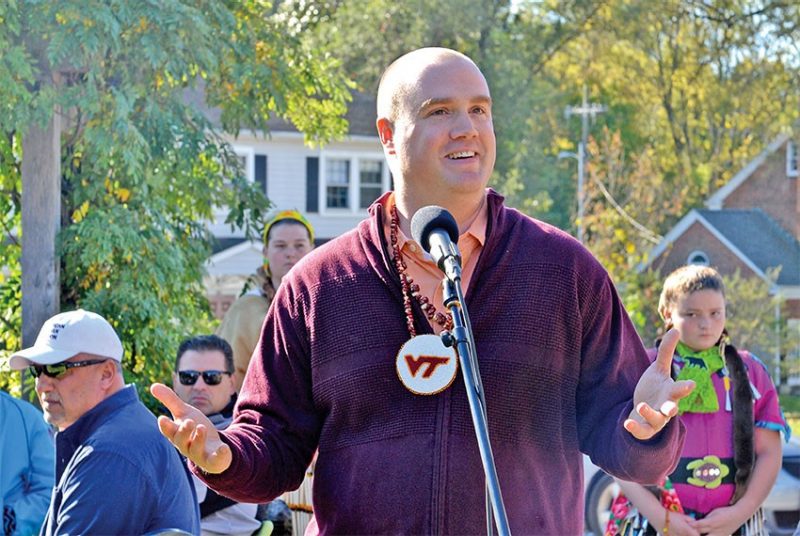

Scott Fralin is the exhibits program manager and learning environments librarian at University Libraries. Photo by Trevor Finney for Virginia Tech.

With “The Land Speaks,” Fralin’s biggest challenge was switching to a digital, rather than physical, exhibit.

“The tools were different, and it’s much harder to create a single experience for all users,” said Fralin. “With an in-person exhibit, every visitor sees the same things arranged in the same way. But when you create a digital exhibit, there is no way to ensure everyone gets the same experience or even sees the exhibit in the same format due to differences in browsers and devices.”

“The Land Speaks” exhibit is a unique product of a transdisciplinary collaboration between Fralin and several faculty members in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences. Desirée Poets and Audrey Reeves, assistant professors of political science, joined Jessica Taylor, an assistant professor of history, in teaching a class, “The Politics of Memory,” under the aegis of the doctoral program ASPECT (Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought).

The main goal of the exhibit is to spread the story of the Monacan Indian Nation. This federally recognized tribe includes more than 2,300 members and has a continuous, thousand-year-old history and presence in the area that is now Amherst County in central Virginia.

Students in “The Politics of Memory” class encountered a number of challenges.

“The students had to learn how to navigate archaeological and historical literature unfamiliar to them, museum exhibit design, and different kinds of sources, from oral history to old photographs and even plant remains from thousands of years ago. They had amazing teamwork and communication skills to navigate these challenges and the COVID-19 pandemic deftly,” said Taylor.

“The course was a great way for us to learn from one another,” said Reeves. “The students brought skills from various backgrounds. A political science student, for example, would be especially sensitive to the political importance of drawing attention to the stories and political campaigns of marginalized groups, as a challenge to attempt to erase or silence these groups.

“Fantastic history students — including those in the interdisciplinary master’s program in material culture and public humanities — were instrumental in identifying precise historical details and expressive artifacts,” Reeves added. “Finally, we were fortunate to have someone with a fine arts background, as artistic sensitivity is also important for designing visual exhibits that should communicate not only facts but also emotions and beauty.”

Rufus Elliott ’07, the first member of the Monacan Indian Nation to graduate from Virginia Tech, worked as a tribal consultant on the exhibit.

“I am grateful I had the opportunity to work with Dr. Taylor and her students to produce an outstanding, one-of-a-kind exhibit,” said Elliott. “It is extremely important that institutions of higher learning take the time to have a collaborative approach when exploring the history of the Indigenous people of Virginia, and Dr. Taylor and her team did exactly that.”

The exhibit team had been working with state archaeologist Tom Klatka to feature real-life Monacan Indian artifacts on loan from the Virginia Department of Historical Resources and a 3D scanning interactive component. Artifacts included beautiful fragments of pots handmade by Indigenous women that had been recovered from archaeological sites.

The original plan called for exhibit visitors to see for themselves the textures and scale and the skill and care put into the artifacts. Those plans had to be discarded because of the pandemic, and Fralin went to work constructing a new virtual experience.

“More than words, objects connect us to their place of origin and in this case, they deepen our understanding of why respecting archaeological sites is crucial to respecting the dead and their living descendants,” said Taylor. “Nothing replaces seeing objects in person, but we are so grateful to Scott Fralin for creating a gorgeous site and adding those elements in virtually.”

Melissa Faircloth, director of Virginia Tech’s American Indian and Indigenous Community Center, weighed in on the online exhibit.

“I especially appreciated the digital models of housing and burial mounds for those visual learners,” said Faircloth, an enrolled member of the Coharie Tribe of Eastern North Carolina. “I think the project is so rich in the value it brings as a learning tool because it intersects with so many areas, from history to art, American Indian studies, and culture, just to name a few.”

“We sought to showcase the political savvy, poetry, art, medical knowledge, family relationships, and all kinds of successes that characterize Eastern Siouan life over a thousand years. Native people past and present have shaped everyday life for themselves and for all Virginians today. The tie between Native custodians and this place is still there,” said Taylor.

“Southwest Virginia has a long and dizzying diverse human history, with thousands of archaeological sites and dozens of descendant communities to prove it,” Taylor added. “The exhibit examines just one piece, the Monacans, to show how over hundreds of years this Indian nation thrived and survived colonialism and racism. It also provides context for their successful pursuit of federal recognition, and the problem that started our exhibit: the fight to save their 17th-century capital of Rassawek from a water station supporting real estate development.”

“Virginia Tech community members should know the very long human history of the place where they live. It’s a central discomfort in U.S. history that the homes, schools, and businesses we love occupy land that has long-standing Native custodians,” said Taylor. “We know that Native people had their land stolen, but we don’t often think about the place we sit at this very moment as stolen. By focusing on this area, we are asking people to think about their own small role in colonialism. The process continues elsewhere, and many sites important to Native people across North America are currently under threat.”

Frailin admits that before working on this exhibit, he had only limited knowledge of the Monacan Indian Nation. “My hope is that this online exhibit will help more people become aware of the Monacan Indian Nation, learn about their past in our region, and become aware of their current struggles trying to save their historic capital, Rassawek, from development,” he said.

The exhibit team wants the community to know that the campaign to save Rassawek is ongoing, even while the Monacan Indian Nation deals with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The great thing about an online exhibit is that more information is just a click away,” said Taylor.

“I think what is so amazing about the virtual exhibit — aside from the amount of detail, context, and history — is how relevant the medium is to our current situation,” said Faircloth, who is also a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology. “This is beautifully done, and it’s sure to be an amazing teaching tool as professors deliver online content this fall.”

Fralin is working on exhibit plans for the fall semester. “I’m taking the lessons I learned crafting this digital exhibit to help plan for the fall,” he said. “My main goal for future exhibits is to ensure they do not present COVID-19 public health risks. And so I’m looking at how to integrate digital interactive components so people can safely leave feedback, write comments, and answer questions posed by future exhibits.” Fralin is looking forward to collaborations with other campus departments on upcoming exhibits.

“I adored working with Scott Fralin, from talking big ideas to design to content,” said Taylor. “I didn’t know that much about design, and he made the process transparent for a novice like me. More people should know what a gem he is.”

Written by Elise Monsour Puckett.