Taking 'Ut Prosim' to Africa

Six years ago, Theo Dillaha, a former Virginia Tech professor, and a group of people with Virginia Tech connections started a nonprofit organization to build a school in Tanzania. Today, the Maasai Education Foundation is teaming with Virginia Tech’s student-led Service Without Borders to build the school and make a difference in many children’s lives

A chance encounter between an American granddaughter and a young girl from the Maasai tribe in a remote part of northern Tanzania sparked the forming of a nonprofit organization and the building of a boarding school that is changing lives in this African country.

That encounter also interrupted the retirement plans of Theo Dillaha, a former professor in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering at Virginia Tech.

“I think we’re all a little shocked at what we’ve done,” Dillaha said.

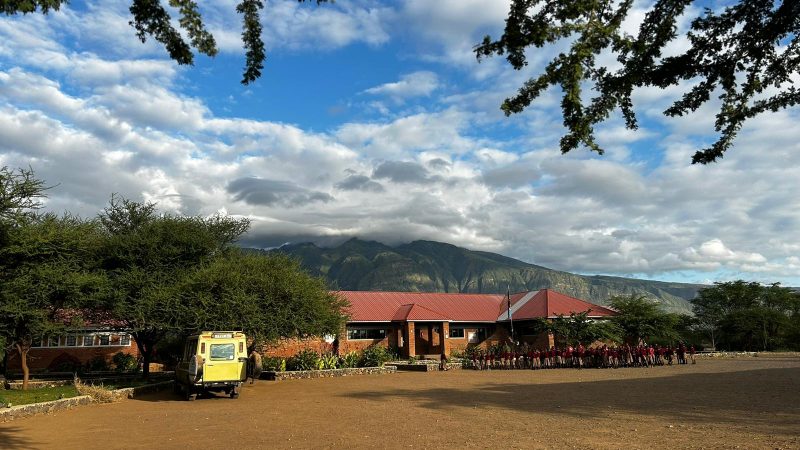

With assistance from many people with Virginia Tech connections, Dillaha, his family, and many of his closest friends have started the Maasai Education Foundation (MEF), which is raising money for the operation of and the building out of the Engaruka English Medium Primary School. This school currently meets the educational needs of approximately 235 Maasai students in the Engaruka region who first attend preschool and then continue taking classes through the seventh grade.

Dillaha retired from Virginia Tech in 2013 fully ready to tackle a long list of projects at his home in Newport, Virginia, roughly 20 minutes from Blacksburg. But Dillaha’s granddaughter, Daphne Kibler, prompted an exciting, albeit challenging, venture.

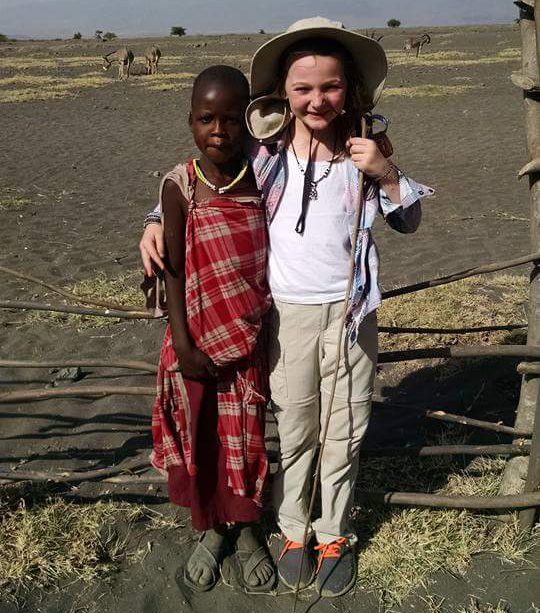

In 2016, Dillaha, his family, and friends traveled through the Engaruka region on a 10-day safari. During one of the group’s stops, Daphne – 7 years old at the time – befriended a Maasai girl of similar age named Maria, who was selling bracelets at the lodge where the group stayed. The group only spent 24 hours there, but the two girls bonded, even though Maria spoke little English.

“There’s not a lot of a language barrier for two kids chasing goats,” Essra Kibler, Daphne’s mom, said, laughing. “Maria was so excited to teach Daphne all she knew about goat herding because that was also one of her responsibilities in the family, and Daphne told me, ‘I'll never forget that. Maria is the bravest girl I've ever met.’”

Maria, though, did not attend a school because few girls in Maasai culture get an education, and Daphne struggled to understand that concept. Upon returning to the United States, her mom decided to become an educational sponsor for Maria. That first meant finding Maria’s family, then getting Maria out of a prearranged marriage at her young age, and finally getting Maria’s family to agree to send her to a school away from the family’s remote home.

“I thought going to school was as simple as us sponsoring the tuition,” Kibler said. “What I didn't know was there were no schools around there. … It was a much bigger ask than I thought I was asking.”

Kibler, a 2002 graduate of the Pamplin College of Business, ultimately connected with Martha Olemisiko, the director of the Engaruka Community Initiative Organization, and Olemisiko found Maria’s family. The family agreed let Maria live with Olemisiko’s family in Arusha, a city located several hours from the family’s home, and attend a school there. Kibler and her mother flew back to Tanzania a few months after their safari trip to meet with Martha and check on Maria.

Olemisiko informed them that she had dreamed of starting an English medium primary school in Engaruka. English medium schools teach in English to better prepare students for secondary schools that teach solely in English. So, after the visit, the Dillahas and Kiblers agreed to help.

Theo Dillaha, assisted by Brian Benham, a biological systems engineering professor and Virginia Cooperative Extension specialist, established a foundation. They put together a board of directors comprised mostly of people who went on the safari, applied for 501(C) (3) status, and the Maasai Education Foundation was officially formed in April 2017.

“We wanted to give donors confidence in what we were doing,” Dillaha said, explaining why the group formed a foundation. “We had to create a vision statement and bylaws. Operating procedures and construction plans to get approval from the IRS. Developing all that really forced us to come together.

“Our first responsibility is to our donors, to be good stewards of their funds. Less than one half of a percent of our donations go to overhead because we are all volunteers. We’ve told our Tanzanian partners that we need to use these funds in the most responsible manner, and we’ve had to work through some challenges, but for the most part, they’re understanding of that.”

Construction begins — and continues

In 2017, the school, with assistance from MEF, had raised enough money to construct a building consisting of two classrooms, two staff rooms, a nurse’s room, a toilet, and showers. One of the classrooms served as a temporary dorm for girls. In February 2018, the school opened, with 48 students starting preschool.

Since then, MEF has raised money to build and complete a dining hall, a six-room classroom building, restrooms, a 120-bed girls’ dormitory, satellite internet, and an improved water supply for the school. Boys are currently housed in an unused classroom. In partnership with MEF, Virginia Tech’s Service Without Borders student organization travels to the school every summer and has funded and constructed a photovoltaic system, a computer laboratory with 20 laptops, a playground, and drip irrigated gardens and orchards.

“It's been an incremental process,” Benham said. “We try to add a class of students every year, and we're getting to the point where space is an issue. We recently completed a girl's dormitory, and the boys now are essentially boarding in the initial classroom, and we need those classrooms to help to expand the classes. The school currently serves preschool and first to sixth grade students. In 2024, we will add seventh grade, the last grade of primary school.

“So the focus of this year’s fundraiser and the focus going forward would be the boys’ dorm. That's a top construction priority. Sponsorships and operating costs are also priorities.”

Fundraising is critical for construction projects, and more importantly, for the success of the school. MEF holds two fundraising campaigns each year, with Dillaha and Benham leading those efforts. They often secure matching funds from businesses, groups, and organizations, and those interested may sponsor a child for $700 a year, which covers tuition, fees, room and board, thus helping with operating costs.

Fundraising also pays for the teachers, a mix of Maasai and non-Maasai people. Olemisiko, her father-in-law, the school board, and a group of teacher representatives oversee the hiring process, which places emphasis on those with the ability to teach English and math.

“The one thing I would point out is we don’t tell the school what to do,” Dillaha said. “We give them advice. We finance much of the operation and all the construction and things like that, but we do not dictate. We may tell them how much money we can provide for a new building or project, but we’re not dictating to them what to do. This is their school. We’re just trying to support them as best we can.”

Virginia Tech students join the efforts

Dillaha has a heart for helping those who live in foreign countries, and a resumé that supports that. He was in the Peace Corps and has worked in places like Morocco, Guam, and Micronesia. During his career at Virginia Tech before he retired, he was on loan to what now is the Center for International Research, Education, and Development, where he managed more than $25 million in United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contracts.

He has been a faculty advisor for Service Without Borders and Engineers Without Borders service-learning programs in Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Haiti, Nepal, and of course, Tanzania, participating in or coordinating projects to better lives in those countries.

In short, he is a Marco Polo of the Virginia Tech professorial family.

As a professor at Virginia Tech, Dillaha was involved with Engineers Without Borders, a national organization of students and professionals who partner with communities around the globe to meet certain needs. He later decided to help when a group of students at Virginia Tech wanted to form a similar club that would include students from all different majors, not just ones from engineering.

In 2016, Service Without Borders was born. This student-led group takes the spirit of Ut Prosim (That I May Serve) across the world, having established partnerships and worked on projects in places like Nepal and India. Virginia Tech students spend the year raising money for their projects, though the group has also received support from the Office of the Vice President for Outreach and International Affairs.

In 2016, the group teamed with MEF to help with the Tanzanian school, and except for 2020 and 2021 – the pandemic years – approximately six to eight Virginia Tech students have traveled to Tanzania each year. This past year, students raised money for 10 laptop computers and fruit trees that were planted in the school’s orchard. In the past, the group raised money for a playground and other construction-related projects.

Jarek Campbell ’21, M.S. ’22, who graduated with undergraduate and master’s degrees in geography from the College of Natural Resources and Environment, joined the organization as a freshman and went to Tanzania in 2019.

While there, Campbell – who now works as assistant director of recruitment for the college – helped to build a playground. On two subsequent visits since then, including a trip earlier this summer, he helped to build the computer lab, teaching the students programs such as PowerPoint and Microsoft Word, and he dug holes for fruit trees and ditches for irrigation.

“The first trip, I would categorize as an adventure,” Campbell said. “The second year I went, I really learned about the people and connected my life to their lives. I kind of closed the gap, I think, between myself and the people in that community.

“This third year, my travel turned from a window to a mirror. Because I had this experience and it wasn't new and I knew what to expect, I was really able to look at this third trip and spend a lot of time to reflect on my life and think about what was important in my life.”

Isabella Munson ’23 echoed similar thoughts. The Bristow, Virginia, native, who is working on a master’s degree in biological systems engineering, spent much of her first three years helping with fundraising and communications efforts for Service Without Borders.

She served as the Tanzania team lead this past year, continuing with those same efforts, but also helping to plan the trip. She wanted to strengthen the organization’s relationship with the Tanzanian students, so she started a pen pal program and managed a reading club in which Virginia Tech students read to the Tanzanian students over Zoom.

Munson, who will be the president of Service Without Borders this year, made her first trip to Tanzania thanks in part to the financial resources provided by the Julia Pryde Memorial Travel Grant and the Pratt Scholarship that supports biological systems engineering students interested in international activities and sustainability. Pryde tragically passed away on April 16, 2007, and her family established the grant in her honor.

“The trip really gave me a perspective on the impact of what we do,” Munson said. “It's given me so many ideas and so much inspiration going into this next year about how to make the club even better and get even more people involved.

“From a life perspective, it obviously gives you a great appreciation for what you come from and the opportunities you have, especially in education. This is a very education-based project. It was a lot easier for me to go through school to get a good education, and I'm planning to come out with two degrees — and it’s a lot harder for those kids, especially in that rural area, to get to that level. I have a much more immense appreciation for that and just life in general.”

University students aren’t the only ones with Virginia Tech ties aiding the cause in Tanzania. Most of the MEF board consists of Virginia Tech alumni:

- Steve Conner, who earned a degree in civil engineering in 1983 and mechanical engineering in 1986 and is the principal engineer for Schnabel Engineering, LLC in Blacksburg

- Margie Lee, who earned a degree in biology in 1982 and a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine in 1986 and is the associate dean for research and graduate studies at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

- Randy Stith, who retired as the director of visual and broadcast communications at Virginia Tech

- Nina Tarr, who earned a degree in human development in 2020 and is the program coordinator at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

In addition, Colin Kibler, who earned a degree in accounting and information systems in 2002 and is the vice president of information security and compliance for Performance Food Group, serves as MEF’s information technology lead.

Figuring out the future

Two years ago, the first class of fourth grade students at the school took a national exam required of fourth graders in Tanzania, and the class ranked in the top 2 percent nationally for schools with less than 40 students per class. The second fourth grade class took the exam last year, and it ranked No. 4 out of 85 schools district wide.

Obviously, the efforts of the Maasai Education Foundation and Service Without Borders are making an impact.

“We’re obviously pleased,” Dillaha said. “We’ve got that feedback now to validate what we’re doing.”

Dillaha said that the foundation’s goals consist of finishing the buildout of the school. That means building the boys’ dormitory, two more classrooms, a small administration building, and teacher/staff housing. Getting that done figures to take two more years.

Longer term, the plans aren’t as solidified. Though her father is more cautious about this, Essra Kibler wants to expand into a secondary school – the American version of high school.

“That’s because the quality of education for these kids is so much higher than even the education that they could get, by knowing English, to get into the Tanzania public schools,” she said. “They [the Engaruka community] think we'll get so many more kids into colleges. That was not in our original vision, and it's a big commitment. We think about four or five more grades, so a lot of dorms and classrooms. I think over time it'll happen, but I think we need to feel more confident in having sustainable income for this goal before we take on another big build.”

They’re exploring ideas for additional income, and the Dillaha and Kibler families and MEF board hope that the foundation and the school can find a model that allows the school to be self-supporting – no small task in a developing nation of 63 million.

Regardless of what eventually happens, though, Dillaha takes pride in what has been accomplished. And even though his retirement hasn’t been exactly what he originally envisioned; it actually has been more gratifying.

“There are two rewards for me,” he said. “I feel good about the impact it has on the students that are going to school – and I feel great about the impact that it has on the Tech students.”