Veterinary college alumni at forefront of effort to contain avian flu and its impacts

From personally escorting a sample on a flight from Virginia to Iowa for testing, to joining a delegation on a trans-Pacific flight to Japan to convince trading partners the U.S. poultry supply is safe, alumni from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine are on the front lines in the battle to control the impacts of the highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak.

Two highly ranking officials working on the outbreak in the U.S. Department of Agriculture — Fidelis Hegngi and Christina Loiacono — graduated in the same Doctor of Veterinary Medicine class at Virginia Tech in 1994.

“The 2015 [avian flu] outbreak is what we used to say was the worst,” said Hegngi, a senior staff veterinarian in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) who has been at work on national avian flu policy for almost two decades “Now, ’22-'23 is the largest highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak ever recorded in the United States and arguably the most significant animal health event in U.S. history, ever.”

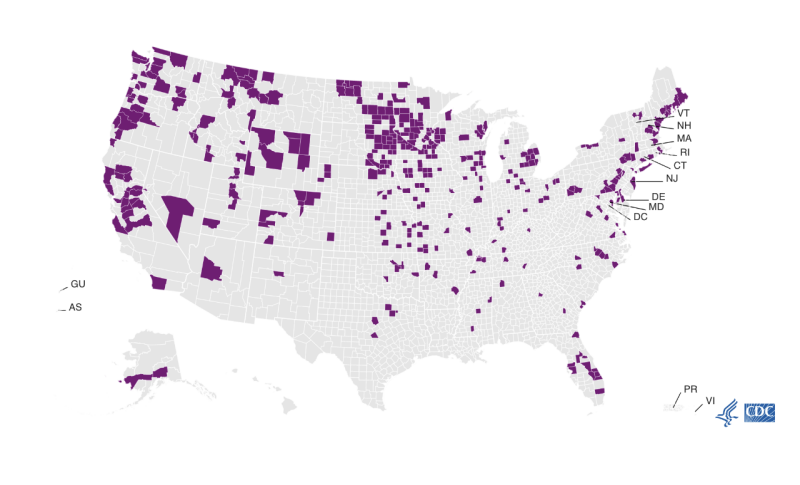

More than 58 million birds have died in the U.S. from highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), spread by a strain of the H5N1 virus, since the first case was discovered in February 2022. The outbreak previously took a firm hold in Europe and spread to the U.S. by migrating waterfowl.

Many Americans have noticed the outbreak’s impact most with egg prices, which went up nearly 60 percent from December 2021 to December 2022 and may go up another 23 percent in 2023, according to the USDA.

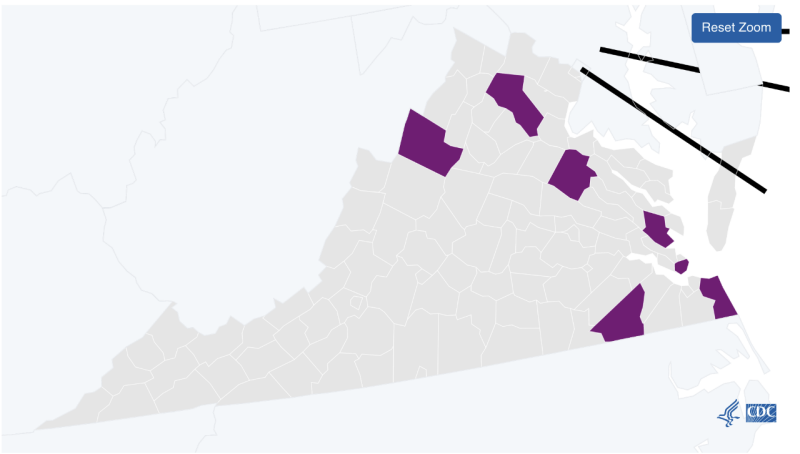

After a handful of scattered confirmed cases in small flocks in 2021, Virginia saw its first confirmed case at a commercial turkey flock on Jan. 19 in Rockingham County, followed by another case three miles to the southwest in a second commercial turkey farm eight days later.

More than 36,000 birds were euthanized and 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) surveillance zones were set up around each positive case to test birds on approximately 200 poultry farms.

Confirming that first case of avian flu in a Virginia commercial poultry farm required some quick action far beyond the call of normal duty for one veterinary college alum.

“One of my favorite stories about this outbreak is the first case in Virginia, was diagnosed at the Harrisonburg laboratory,” said Loiacono ’90, DVM ’94, coordinator of the USDA’s National Animal Health Laboratory Network. “Jessica Walters is the director there. She had a non-negative result in her laboratory. It needed to come to Ames, Iowa, for confirmation. Well, she got on a plane on a Sunday and hand-carried that sample to Ames, Iowa, for testing, dropped it off, got back on the plane, and went home so that they could get the sample to us as fast as possible to get the confirmation.”

Walters ’09, Ph.D. ’14, DVM ‘16, the Harrisonburg-based program manager for the Office of Laboratory Services with the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Service (VDACS), was uncertain commercial delivery services would be able to get the sample to Iowa in time.

“I jokingly said, ‘I’ll just look up flights from Charlottesville, and I can have it in Ames, Iowa, by 11 a.m. tomorrow,” Walters said. “And the response I got was, ‘Well, that might be the best option.’ I called my husband and said, ‘Well, it looks like I'm flying to Iowa in the morning.’

“So I got up at 5 a.m. and boarded a plane and took the sample to Ames, Iowa. Someone from the lab met me at the airport. I handed off the sample, and they had confirmatory results by the time I got back to the Charlottesville airport.”

Two detections of avian flu and the overlapping 10-kilometer surveillance zones around each in the heart of Virginia’s poultry production epicenter resulted in a steep increase in the workload for Walters’ lab, which shifted its more routine testing to other state facilities so the Harrisonburg lab could focus on the outbreak.

“In what I call peacetime, we average about 150 to 200 samples a week,” Walters said. “Since the first detection, we have run close to, if not a little bit more than, about 3,000 samples.

“We have enhanced all of our processing for any of those samples that are coming in, they go through a decontamination process. We’ve had to ramp up our facilities.”

All over the U.S., labs like the one Walters oversees analyze local samples, beginning a process that culminates in monitoring and policy at the state and national level, also overseen in part by veterinary college alums.

Hegngi, originally from Cameroon, is the senior staff veterinarian for Aquaculture, Swine, Equine & Poultry Health Center strategy and policy with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Veterinary Services.

As national coordinator of the live bird marketing system, avian influenza program, Hegngi was on the ground floor as the United States began developing its avian influenza strategy, policies, and procedures in 2004. Currently, he is part of a situation unit within an incident command group focused on the ongoing avian flu outbreak.

“My big role in my own subgroup now is the situation report,” Hegngi said. “So there is a report that is put together that starts at the state level. It goes to our district offices level, then it comes to me and two of my colleagues. We review that document that is then sent out, that goes through all the different governmental agencies that are involved, right up to the secretary of agriculture, to see what is happening every day.”

Part of Hegngi’s role is also to help assure trade partners that the U.S. poultry supply is safe and available, such as on a mid-February visit to Japan. Hegngi said only 12 percent of U.S. annual egg-laying poultry are affected by avian flu, just 4.5 percent of U.S. annual turkey production, and less than 0.1 percent of broiler chickens, by far the largest segment of the U.S. poultry industry.

“They're taking me to Japan as the poultry expert, to be able to explain to Japan what is happening in the U.S. with the outbreak,” Hegngi said, “so Japan can calm down and not be scared that they're not going to get poultry and poultry products from us, or that they can get product that might bring the disease to them.”

Loiacono oversees an intricate network of laboratory facilities where animal samples are tested for a variety of diseases. The veterinary college has one of the labs in the network, Virginia Tech Animal Laboratory Services, overseen by Tanya LeRoith DVM ’99.

“I get to work with directors in laboratories around the country and diagnosticians around the country,” Loiacono said. “It’s just great to be supporting the work that they do, because they're doing all the hard work. I'm just trying to help keep all the wheels going in the same direction.”

At a state level, it is Carrie Bissett DVM ’04, who keeps the wheels rolling in unison as incident commander for the response to the two cases in Virginia.

“I'm like the master chess player, moving people around and telling them what to do,” Bissett said. “We’ve got about 30 responders, between my staff here at VDACS and the USDA, and a few federal contractors. That’s the breadth of the response with what we're looking at right now with the commercial turkey detections that that we're responding to currently.”

In her regular role as director of veterinary services within the state agriculture department, Bissett supervises other veterinary college alums in her office. Graduating from the veterinary college provides a common point of reference within Bissett’s office, she said.

“I think that once you kind of have that common ground, you can even now talk about professors that everybody had, or, when I was there, the commons room didn't look like it does now,” Bissett said. “There's that common ground that you have, and you know, I've got six or seven vets that work for me, and majority of them are Virginia Tech grads, and that’s sort of the immediate bonding that you have.”

The tangled web of connections also breeds familiarity between veterinary college grads in different agencies.

The lab Walters oversees in Harrisonburg is a member of the national network supervised by Loiacono, who Walters describes as “my subject matter expert when it comes to testing requirements.”

Walters also enjoys collegiality with fellow alum Bissett, based in Richmond, who is her counterpart in state agriculture and consumer services as a program manager of a different office.

“So basically, my laboratory testing is the foundation for the decisions that she makes,” Walters said of Bissett. “And so we work very, very closely together. And, our two entities really kind of combine in order to get the full response for this entire outbreak. ... I think both of us just truly have a passion for Virginia agriculture.”

Common veterinary college ties can also help bridge the distance with Hgengi at the federal policy level, Walters said.

“I will say it is very nice to be able to go to someone like Fidel at meetings, even though he's much higher up in the USDA,” Walters said. “Since he is a Virginia Tech alum, I feel a lot more comfortable being able to go have conversations with him because of that link.”

Experiences while at theveterinary college helped guide each of the four toward their current positions, often with unexpected turns from their mindsets as students.

“I started veterinary school to be an equine practitioner,” Loiacono said. “I grew up with horses and intended to spend my life working with horses. I met a pathologist in my senior year.” It was the late Bob Duncan, who worked in a state lab before joining the veterinary college faculty, who Loiacono said “turned me on to pathology.”

Loiacono worked two years in private practice but said she “did not enjoy it very much.” She went into a pathology residence at the University of Missouri and then was hired by the USDA as a technologist, ultimately leading to her roles as assistant director and then director of the national laboratory network.

“I never, ever thought I would be in the position I am today, but I had the opportunity and it's become, I would say, my dream job,” Loiacono said. “I feel like it's the niche that I was waiting for.”

Bissett also entered private practice, mostly small animal, after graduating from the veterinary college but decided to get a degree in public health through the University of Iowa – Virginia Tech had not yet launched its public health program. She started working in animal welfare for the Virginia Department of Agriculture, working up to her current program manager role over a decade.

“Some of my favorite teachers have nothing to do with what I'm doing now,” Bissett said. “But they were still a great influence on just learning how to think. I think that's a skill that we don't often think about, but there's that logical problem solving, learning how to think your way through something.”

Walters started out to be a company veterinarian in poultry, but along the way of her DVM, discovered an affinity for laboratory work.

“I wasn't a huge fan of the lab work. I really liked being out in the field,” Walters said. “But my fourth year when I was doing my rotations, I actually did a rotation with the poultry diagnostician here, and I really, really liked it.”

Walters eventually moved into that same poultry diagnostician role with the commonwealth, later entering management at the Harrisonburg lab as she and her husband decided to relocate to the Shenandoah Valley.

Hegngi, a recent recipient of the U.S. Poultry & Egg Association’s Lamplighter Award for “sustained and exemplary service” to the poultry and egg industry, said he quickly learned at veterinary school that he wasn’t that interested in working with dogs and cats, and getting kicked by a cow discouraged him from going the large animal route.

His mentor at the veterinary college was Bill Pierson DVM ’84, Ph.D ’93, professor emeritus of biosecurity and infection control and clinical specialist in poultry health and 2022 recipient of the Bruce W. Calnek Applied Poultry Research Achievement Award. Hegngi continued to work with Pierson at commercial poultry operations in the Shenandoah Valley for three years after graduating with his DVM.

Hegngi said he often counsels students not to box themselves in to one type of veterinary medicine and to consider his own journey.

“I try to always convince them to come my route,” Hegngi said. “When you look at your training, you've been given an unbelievable education. I still think that a vet has to be smarter than anybody, because we deal with so many multiple species and patients who cannot talk to us that it is unbelievable."

“I always tell them, 'Don't have tunnel vision. Don’t sit there and think you can only practice medicine with dogs or cats or cattle,'” Hegngi said. “Diversify your knowledge. Every country in the world, every religion in the world, eats poultry, so think about it, you’re going to make a good living, you’re going to make good money.”

Veterinary college connections in the avian flu response stretch even farther than Walters, Bissett, Loiacono, and Hegngi.

At the Virginia Veterinary Medical Association conference in Roanoke on Feb. 17, Sarah Firebaugh ’09, DVM ’13, a veterinary medical officer and poultry specialist with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, co-presented a session on the response in Virginia with Bissett. Firebaugh has been involved with avian flu response in several different states.

“It doesn’t pick them off one at a time. You’re going to see mass mortality,” Firebaugh told the session about how the highly pathogenic avian flu acts in susceptible flocks.

Among other veterinary college alums assisting with the avian flu response in Virginia are Dan Hadacek, VDACS regional veterinary supervisor and operations chief for the incident; Bruce Bowman, subject matter expert for composting; Tabitha Moore, VDACS field veterinarian serving as oversight for permitting in the flu response; and Tom Lavelle, VCADS regional veterinary supervisor overseeing composting and decontamination

The highly pathogenic avian flu outbreak continues with no firm ending date. A spring uptick is expected as migrating waterfowl return north from wintering sites, spreading the virus through droppings and mingling with other birds.

“The biggest challenge is that, unfortunately, it doesn't look like it's going away,” Bissett said. “It’s spread by wild waterfowl. So as long as we have waterfowl migrating north and south to their breeding grounds and vacationing grounds, then you know, we've got the risk of avian influenza flying over our heads constantly.”

Experts stress that avian flu shows no current evidence of transmitting among people and that it cannot be transmitted by eating poultry or poultry products like eggs. They urge farmers and producers to keep poultry separated from waterfowl as much as possible and to use different footwear to access coops and poultry houses than that used around ponds and lakes.

Veterinarians trained in Blacksburg will continue making extraordinary efforts to keep the food supply safe and whatever else it takes to keep the outbreak from worsening.

“The poultry industry is near and dear to my heart,” Walters said. “And I will pretty much do whatever I need to do to protect it.”