Augmented reality brings museum exhibits to life

A Virginia Tech team is bringing museum exhibits to life by creating a complete digital skeleton of a Teleocrater rhadinus — an animal that predates the dinosaurs — to serve as the centerpiece of an immersive educational experience.

This interactive learning environment will include digital replicas of all individual bones as well as a mounted 3D-printed skeleton. The related educational materials will be accessible worldwide, filling in the holes between what our scientists know today and the Earth's history.

The Modern Skeleton: Translating Natural History into Interactive and Immersive Experiences project was made possible by a $25,000 Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology Major SEAD Grant. Led by paleontologists Sterling Nesbitt and Michelle Stocker in the Department of Geosciences, the team aims to close the gap between static skeleton displays in museums and digital access to the wealth of information they possess.

“Right now, there’s only static skeletons in museums around the world, so most of the interaction is passive,” said Nesbitt. “You can look at a specimen or a skeleton and see its physical structure, but the only information about that animal is on a small panel in front of the exhibit. So what we're doing is making that panel more integrative to the animal itself. You can literally scan the bones with your phone and transport into a digital environment.”

The project’s digital skeleton of the Teleocrater rhadinus was created from original fossils and will be 3D-printed as a freestanding skeleton that participants can interact with through an augmented reality app. Through this app, visitors can learn about the importance of the animal, how and when the animal was found, relationships between skeletons, and how the virtual experience was created.

Living over 245 million years ago during the Triassic Period and predating dinosaurs, Teleocrater was unearthed in Tanzania, East Africa, and named by Virginia Tech and other paleontologists in 2017. This creature is a cousin to dinosaurs, has a long neck and tail, walked on four crocodylian-like legs, and was approximately 6 to 7 feet long. Carnivorous Teleocrater is one of the oldest relatives of dinosaurs that has ever been discovered, and its bones are temporarily housed on Virginia Tech's campus.

“The paleontology itself is a big deal,” said Todd Ogle, executive director of Applied Research in Immersive Experiences and Simulations (ARIES) at University Libraries. “With refinement, these ideas and approaches developed in the project might just find their way into larger places like the Field Museum in Chicago or internationally known museums like the National History Museum in London. That is a big deal.”

Theoretically, this augmented reality experience can be created for any fossils, including 3D-printed ones, with a digital scan.

“It’s a way to bring these animals back to life in a way that we haven’t been able to because of technological barriers,” said Nesbitt. “It’s getting easier and cheaper to be able to tell these stories, and now viewers can actually interact with these animals that are hundreds of millions of years old.”

ARIES is responsible for developing the augmented reality app as well as the preparation and optimization of the 3D models of the bones that University Libraries’ 3D Scanning Studio, led by Max Ofsa, Prototyping Studio manager, scanned from original fossils. University Libraries’ 3D scanning technology is highly accurate and captures not only the shape of the bones but also the texture and color. The project will make engaging experiences for Virginia Tech Museum of Geosciences visitors. The group also is working with partners in Tanzania to also translate the app into Swahili.

“I got to digitally sculpt the skull, which was fun,” said Nesbitt. “The ribs, however, were challenging. If the ribs don’t look right, the whole animal doesn’t look right. The ribs alone have taken months and months.”

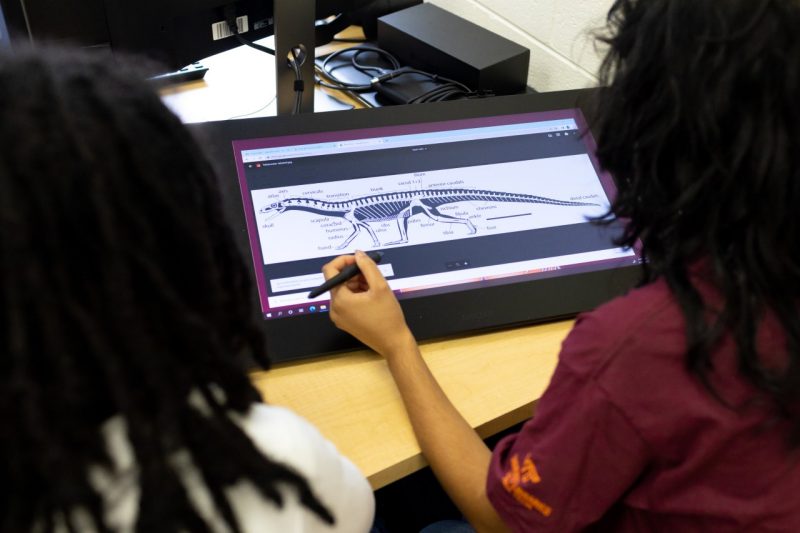

A team of library student employees are assisting with this project. “Our students are not only interested and engaged but capable of developing the immersive experiences,” said Ogle. “Student artists and programmers, when working directly with subject matter experts, can make immersive experiences that are meaningful and impactful for others while gaining valuable experiential learning opportunities.”

“This is a highly integrative project,” said Nesbitt. “It’s augmented reality people talking with education people, talking with scientists. Just locally, the collaboration has been amazing. What’s flown out of that is a bunch of students interacting too. Showing undergraduate students how a process like this works and how much goes into reconstructing a skeleton was one of our ultimate goals.”

“It’s really exciting to see collaborations across fields with this project and to see so many people learning about new ways to work on their topics of research,” said Stocker. “Working with the library and TLOS [Technology-enhanced Learning and Online Strategies] is helping us understand the paleobiology of these extinct creatures better and that all plays into how we can share what we know with the public.”

The use of augmented reality to enhance museum experiences has been mainly in the hands of large institutions, working with corporate partners such as Google and Framestore. This team’s approach is intended to make these experiences more accessible with a higher impact.

So far access to the Teleocrater skeleton has only been from one place - Tanzania. “Since we are scanning the bones, we will be able to send the files to anyone in the world instantaneously,” said Nesbitt. “It’s like an open source dinosaur relative. That’s the way I like to think about it. It’s not like anyone has been hiding these specimens, but there’s only a few bones of many of these and they are only in one place in the world. So even for scientists, a lot of the information about Earth history is not easily accessible, which is a shame. Digitally though, it could be looked at anywhere in the world with an internet connection, and that’s what we are trying to achieve.”

Stocker is working with Phyllis Newbill, associate director of educational networks in the Center for Educational Networks and Impacts, part of the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology, to make sure the educational products they produce will help learners meet instructional goals, including both knowledge-based goals and attitude-based ones.

“The project will impact the richness of experience for museum visitors who have in the past simply looked at reconstructed skeletons in three dimensions,” said Newbill. “This project will allow learners to access just-in-time information about the skeleton in context. Because the 3D model will be so accurate, other educational organizations can 3D-print a copy of the skeleton. The accessibility of the information reaches new levels and improves the educational experience while making the information more accessible.”

“We are stubbornly sticking to our goal of accessibility, which means delivery via the web,” said Ogle. “That poses challenges for augmented reality development today, but we believe that it is the direction we must head for the future.”

Ogle said he has been passionate about augmented reality for 20 years and museums his entire life. “Bringing the two together and working with world renowned experts in paleontology, while making such experiences accessible to our own students at Virginia Tech, is a career highlight for me.”