Skill with Rubik’s Cubes leads to career switch for Virginia Tech alumnus

A combination of creativity, intelligence, and athleticism has led to Simon Shi making a living as a social media influencer and a professional triathlete

His fingers grasped the 3-by-3 iconic cube, and he subconsciously started searching for any of the puzzle-solving algorithms digitally imprinted in his supercomputer of a mind. Then those fingers, examples of dexterity, nimbly started spinning the movable rows both vertically and horizontally in dizzying fashion.

Twenty seconds later – in the time it takes to tie a shoelace – Simon Shi had solved a Rubik’s Cube.

“I have four steps,” he said. “A beginner’s method is seven steps.”

Shi ’20, a former Virginia Tech swimmer, has taken his ability for solving Rubik’s Cubes of all sizes and shapes and turned that into a thriving social media business. He’s also twisting his natural athleticism honed from years of swimming into an unlikely career as a professional triathlete.

The odd tandem seems counterintuitive for Shi, who graduated from Virginia Tech with a degree in computer science from the College of Engineering and worked as a software engineer for General Motors following graduation. But this Renaissance man, who currently resides in Flagstaff, Arizona, has found that personal revolutions provide a steady, albeit unique, income.

First, his Rubik’s Cube fixation.

Rubik’s Cubes have been around for more than 40 years. Invented by Hungarian sculptor and professor Erno Rubik, the Rubik’s Cube became a craze in the early 1980s. Interest gradually waned, but variations of the cube and the evolving of “speedcubing” tournaments (solving a Rubik’s Cube in the fastest time) led to a revival. Today, according to Forbes, more than 450 million Rubik’s Cubes have been sold worldwide.

As a 12-year-old, Shi found one lying around his parents’ home in Leesburg, Virginia, one day and became fascinated with it. He then later saw someone actually solve it in person.

“First, I took all the pieces apart and put them back together to complete it,” Shi said. “So that was cheating. When I showed my parents, they said, ‘Now you have to learn how to solve it.’ And then, that's when I learned how to solve an actual Rubik's Cube.”

Shi uses a couple of different complicated algorithms to solve the puzzles, some of which he has posted on his personal YouTube channel. His interest in Rubik’s Cubes coincided with the time when YouTube started becoming more mainstream, with amateurs posting videos and both people and organizations using the site to launch original content. In 2009, Shi launched his first YouTube channel, TheSimonShi.

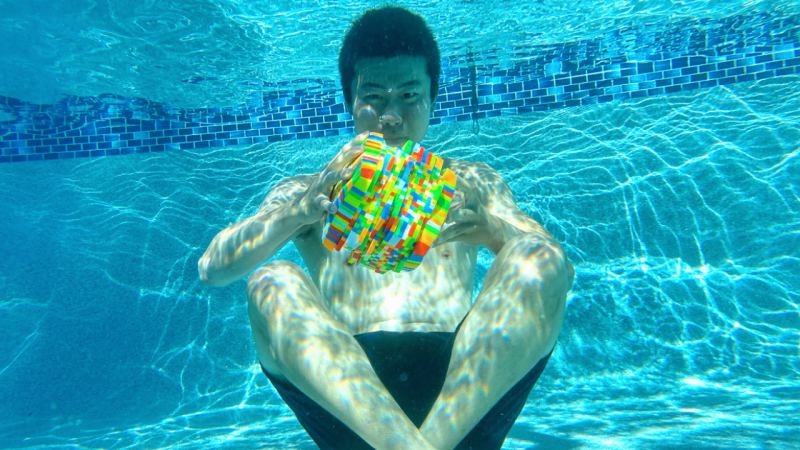

Many of Shi’s earliest videos involved him playing the flute or oboe – two of the seven musical instruments he knows how to play. But within a year, he started posting videos of him solving Rubik’s Cubes of all sizes and shapes in varying environments. A year ago, Shi took on his biggest challenge to date, solving a 17-by-17 Rubik’s Cube with more than 1,700 pieces – underwater.

Wearing a weighted vest to keep him underwater while sitting in a chair in a 3-foot-deep section of a swimming pool and breathing through a snorkel, Shi spent nearly four hours working on the puzzle before finishing it. The subsequent video on YouTube has received more than 2 million views.

“I do insane challenges,” Shi admitted. “I'm trying to get an official Guinness World Record plaque for a Rubik's Cube challenge.”

Shi has 309,000 subscribers to his main YouTube channel. He also has three other YouTube channels, including ones for triathlon training and financial advice and one for YouTube shorts (videos of less than 60 seconds) of him solving Rubik’s Cubes.

The numbers are staggering. A video of him solving a 13-by-13 cube in his living room has registered 16.2 million views. One of his YouTube shorts – him sitting in a chair solving a 17-by-17 Rubik’s Cube – has received more than 73 million views.

Such a following makes Shi attractive to advertisers. Shi participates in the Google AdSense program, which matches advertisers to channels based on content and visitors. Advertisers bid to show ads in the ad spaces on Shi’s videos, and the highest-paying ads get shown. Shi then gets paid based on how many visitors click on those ads.

Most advertisers find this a cheaper way to advertise than through traditional broadcast networks, according to Mike Horning, an associate professor in Virginia Tech’s School of Communication. Also, this way of advertising allows advertisers to get their ads in front of specific audiences.

“One of the innovative things about social media is that it delivers what we call micro-targeted content,” Horning said. “I'm a fly fisherman, so I can watch fly fishing videos all day long, but I can't do that on a television network. On a platform like YouTube, I can not only watch them, but I can also pick the ones that I like. … If you can find a niche where you can deliver content that audiences really engage with, it makes you valuable to advertising sponsors that are relevant to that content.”

In addition to securing sponsorships for his YouTube channel, Shi also has sponsorships through social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook. As a professional triathlete with a high-volume social media presence, he finds himself in demand from companies with products related to athletics.

That makes Shi’s foray into triathlons a lucrative side hustle and something he never expected. Shi never even dreamed of becoming a triathlete, but decided to reach for something beyond swimming while at home after the COVID-19 pandemic ended his senior season in 2020. Looking to stay active, he added biking and running to his daily exercise regimen.

“I didn’t want to just swim because it was kind of boring, looking at a black line at the bottom of the pool all the time,” Shi said.

Shi’s first competition as a triathlete was in a half Ironman – 1.2 miles of swimming, 56 miles of biking, and a 13.1-mile run – in St. George, Utah, in May of last year. He finished in the top 200, completing the course in five hours.

Shi learned, though, that he needed to pick up his training to be as successful as he wanted to be.

“It was tougher than what I was expecting,” Shi said of his first event. “It was very hot. I was cramping up on the run, and so, I learned that I was not drinking enough or taking enough electrolytes during the race. Sovthat was just a good experience. Doing a half Ironman for my first triathlon is kind of like a big step. People do the shorter races to start out, but I wanted to do a big race. … It was a cool learning experience.”

Shi’s increased training paid off in early July when he won the TriWaco Triathlon in Waco, Texas, beating his personal record by nine minutes and winning by eight minutes over his nearest competitor. Earning his professional license in less than a year, Shi plans to test himself again at a half Ironman in Waco on Oct. 16, and he ultimately aspires to be an Olympian in the sport either in 2024 in Paris or 2028 in Los Angeles.

This past March, Shi bet on himself in a big way, quitting his job with General Motors to pursue his interests on a full-time basis. In many respects, Shi lives the life that many 24-year-olds dream of: He makes videos for his YouTube channels and works out.

Yet there are inherent risks; big ones.

“A lot of people don't realize that it is a full-time job,” Horning said. “It’s not like you just make a YouTube channel and a 30-minute show or whatever it might be. You also have to know how to promote yourself through a variety of social media in order to direct audiences back to you. So that means you're probably going to need a channel on Facebook or Twitter or Instagram. It also means that you're going to have to write scripts for your content, work on good lighting, and that you've got to think about how to edit your video. It's not something you do in five seconds. It’s a real job.

Horning continued, “I think there are there are demographic concerns that a person probably has to think about, too. Twenty-somethings probably want to watch 20-somethings things, and so if people want to make a career out of this, they're probably going to have to think about how they might shift their content over time, because they may find that they have aged out of a certain kind of content. They may have an opportunity to do a different kind of content, but places like YouTube are still enough that we don't know that for sure if people can make a lifetime career of it.”

Shi, who had multiple conversations with his parents, his colleagues, and his friends, said he was aware of the risks.

“Every big entrepreneur would say that they took some risk at some point in their life, and that's how they became successful,” Shi said.

Shi certainly appears to be well on his way toward future success. Success can be defined in many ways, even through the unique combination of social media influencing and being a professional triathlete.

One thing is for sure, Shi’s successes will be well documented – by him. And the world will know.

“Some people, they're like, ‘Wow, that's amazing,’” Shi said. “Some people are like, ‘Oh, but is that really what you do?’

“I think, for some people, they don't really know that type of lifestyle, but it exists. They're so used to people who are like, ‘Oh, like I'm a this at Google. I work at this company.’ But doing the thing that I've done, there's definitely a ton of people, hundreds of thousands of people, doing this lifestyle — YouTubers and pro athletes, basketball players, football players – that people watch all the time. That’s their lifestyle, so I think it's pretty cool to give them more information about mine.”