What a difference a yearling makes

The foal of a rescued mare with no available history, Picasso is now a spirited yearling, thriving in a small herd. Owner Amiya Veatch turned to Virginia Tech's Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center and its Foaling Out Program for specialized care.

Resting on a cushion of clean hay, the pregnant mare appeared calm. Her glistening black tail, finely braided, was arched. A fan hummed in the corner.

It was spring outside, the height of foaling season at Virginia Tech’s Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center (EMC) in Leesburg, Virginia. And this mare was delivering.

Gathered at the stall door, a handful of technicians in scrubs looked on intently, murmuring in wait.

In one graceful movement, the bay mare shifted her weight and rose. Her tail twitched, swishing from one side to the other, then settled.

A single brown leg, its tiny hoof sheaved in white, protruded from the mare’s birth canal. The delivery wasn’t progressing.

The attending veterinarian, Krista Estell, a clinical assistant professor of equine medicine, gave the word: “Can we get this baby out, kiddo?” The mare remained motionless, her head bowed, as four clinicians entered her stall, the metal door clanking behind them.

Estell walked directly to the mare’s rear. Wearing blue surgical gloves, she planted her feet, bent her knees, and grasped the leg, straight as a string, with both hands. She pulled downward.

Next to her, equine medicine resident Megan Marchitello swiped the mare’s tail aside and grabbed the foal’s other leg, now visible. A technician stood at the mare’s head, a gloved hand lightly on her muzzle.

Leaning back, Estell counted in rhythm as the two women tugged: “One, two, three; one, two, three; one, two, three.” They squatted with each pull. “Down; one, two, three; down; one, two, three.”

“C’mon, Momma,” Estell chirped. The foal’s hindquarters appeared. “Now we’re cooking. Good job, Mommy.”

After a few seconds, Estell gave the command: “Okay, I need someone to catch this foal. Get some towels ready.”

At once, the stall swirled with activity. Two technicians grabbed towels; another three swung open the stall’s door and entered. They circled the mare in a choreographed routine, then crouched around her, holding up towels as if offering gifts.

With a flourish, the foal burst out in one fluid thrust and was lowered to the hay. “Okay, let’s sit baby up. Take Mommy a step forward,” Estell said, directing the technician positioned at the mare’s head.

The team surrounded the new foal and briskly cleared away the translucent birth pouch. With the towels, they formed a soft ledge along the foal’s back, a cradle of support.

“Okay, everyone out,” Estell said. The women moved in unison. “Good job,” one of them whispered before she stepped through the stall’s doorway.

His regal legs folded, the foal shook his head rapidly back and forth, and touched his nose to the hay, discovering its smell.

And then the mare leisurely turned and lowered her head. She sniffed her new foal from head to toe and back again, and began licking his flank, over and over.

His name would be Picasso, and he would become, as Estell later described him, “a strapping weanling.”

The rescue

Named Mona Lisa because a scar beside her lip makes her look as if she’s smiling, the mare belongs to Amiya Veatch, a member of the EMC Advisory Council and the wife of Virginia Tech alumnus Jeffrey Veatch (finance ’93), who currently serves on the university’s board of visitors.

One morning at the couple’s home overlooking the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia, Amiya was drinking coffee and watching the news. A story about some abandoned horses in southeastern Maryland caught her attention.

In March 2018, acting on a report received from operators of a news helicopter for a TV station in nearby Salisbury, the Wicomico County Sheriff's Office and the Wicomico County Animal Control discovered some 100 horses barely alive, roaming among dead horses in varying states of decay, on a 150-acre property on Maryland’s Delmarva Peninsula.

A longtime rider and horse owner, Veatch immediately picked up the phone and called Wicomico County Animal Control. She was told that her help wasn’t needed. About a month later, however, a neighbor forwarded her an email from a rescue organization and urged her to respond.

“I followed up,” Veatch said, “but they were being a little protective … because they were getting so much media attention.” Once the organization agreed to let her visit, she said that her instinct told her to take her horse trailer.

The group was caring for about 35 rescued horses. “I walked around and visited all of them,” Veatch said. She selected a young chestnut first, whom she would name Peanut because of his size.

“Peanut was the most emaciated horse I had ever had contact with, and he was the only one that actually came up to me. He stood right next me, and he was so weak. I have small hands, but when I put my hand on his chest, it was wider than his chest,” Veatch recalled. She turned and told the rescue group, “This one’s coming with me.”

She then visited several pregnant mares in a paddock. “In my mind,” she said, “that was the only way I could get more horses in my two-horse trailer.”

Among the Appaloosas was a lone bay mare. The first Appaloosa that Veatch selected — “probably the most emaciated who needed the most help” — refused to board the trailer for nearly an hour. Veatch returned to the paddock and looked at the bay mare, who had the best conformation of the group. “I called her Momma at the time,” she said. “It took us about 45 minutes to get her in the trailer. Peanut was so small, weak, and emaciated that we literally picked him up and just placed him beside her.”

Sanctuary on the river

On their farm in Fort Washington, Maryland, across the river from their home, the Veatches already had two geldings in a beautifully renovated barn: august Denver’s Davinci, Amiya’s main mount; and an older palomino, Thor, with an impressive white mane. The pair freely roamed the waterfront pasture, accompanied by a lively barn dog, Dex, himself an adopted stray.

Like statesmen, the geldings accepted the newest members of the herd graciously. “It was so rewarding to see them thrive in the pasture, especially Peanut,” Veatch said. “A day after he’d arrived, he collapsed, and I thought he was dying. He was so weak that he could hardly walk. It was weeks before I saw him actually trot.”

In the meantime, Veatch was eager for her rescued mare to deliver.

“I’ll say I had a really big epiphany. At the time, my son was around 6 months old, so I was getting up in the middle of the night to check the baby monitor — and the horse monitor,” Veatch said.

Not knowing when Mona Lisa would give birth, much less if the delivery would go smoothly, she simply couldn’t justify her watch. “I just came to the realization that I was not prepared or equipped to deliver a foal in my barn,” she explained. In short order, Mona Lisa was loaded onto the trailer and driven to Leesburg.

Veatch’s epiphany was on the mark. Under EMC’s watchful eye, Mona Lisa didn’t foal for another three months.

Quality of care

At EMC, Mona Lisa was enrolled in the center’s Foaling Out Program. “It’s a really great program that’s specific to mares, both high-risk mares and normal, healthy mares whose owners just want a little extra TLC and monitoring,” said Estell, an equine internal medicine specialist. “The mares stay here in the hospital, and we monitor them daily. Skilled technicians are present 24 hours a day to keep a close watch on them, particularly as the mares get closer to delivery.”

Mona Lisa’s primary caretakers were Estell and Elizabeth MacDonald, a clinical instructor of equine medicine, who were assisted by the center’s residents and interns, as well as a new shift of technicians every eight hours.

Although all of the mares enrolled in the Foaling Out Program are attended primarily by EMC’s internal medicine service, the center’s theriogenology (reproduction and breeding) service is available for consultation, as is the surgery and anesthesia team, which can assist at a moment’s notice if the mares need help during foaling.

“There are definitely special considerations for mares that have no history available, like Mona Lisa,” noted MacDonald. “She was very skittish and difficult to handle when she first arrived, probably because she wasn’t used to being handled on a regular basis. So, bringing her here was helpful. We were able to work with her every day, get her to start to trust us a little bit more, and get her into a routine that was comfortable for her. She began to realize that things weren’t as scary as she’d thought.”

In the absence of a medical history, the clinicians carefully checked the mare’s body condition and assessed if she was growing appropriately for her stage of gestation. In addition to administering the appropriate vaccines, the team ordered an ultrasound to evaluate if Mona Lisa’s fetus and placenta were healthy.

And then the wait was on.

It's a boy!

As soon as Mona Lisa started showing signs of labor, the entire team was mobilized. Because the mare did require assistance during the birth, her time in the Foaling Out Program proved to be indispensable.

“Her foaling went pretty well,” Estell said, “but the foal got stuck about halfway out of the birth canal. Since we had established that relationship with her, we were able to help her deliver her foal.”

“She trusted us to enter the stall and look after her foal,” added MacDonald. “It was safer for her and safer for us to be able to assist her — and also safer for us to then go and evaluate the foal once it was on the ground.”

Besides delivering, in Estell’s assessment, a “nice, spunky, healthy colt,” Mona Lisa tolerated the birth, along with the swarm of staff in her stall, like an old pro.“You’re never sure what you’re going to get in these rescue situations,” Estell said, “especially when the mares have been neglected or have experienced poor nutrition. But that foal hit the ground just full of fire and has grown to be a strapping weanling.”

Mona Lisa also took to motherhood quite naturally, without incident.

“We never know if mares are going to enjoy being mothers or not, and she seemed to love her foal,” MacDonald said. “She did so well that there was no need for any aftercare, except routine, close monitoring to make sure she started passing manure, she had an appetite, and she continued to drink water and also to ensure that she tolerated her foal and produced enough milk. She did all of those on her own.”

Over the many weeks of Mona Lisa’s stay and the additional weeks after the foal’s birth, the EMC team kept Veatch apprised of each day’s progress.

“Mona Lisa’s owner trusted us,” MacDonald said. “She loved and appreciated our daily phone calls and the text messages we would send intermittently with photos so that she could see how her mare was doing.”

The happy, healthy herd

Mona Lisa and her foal remained at EMC for about six weeks, and Veatch first met the foal when he was 3 weeks old. In all the excitement, she admitted that naming him was a little difficult.

“In my mind, I just knew the foal would be an Appaloosa because the majority of the rescued horses were Appaloosas,” Veatch said. “And for some reason, the name Picasso fit. But when he was born, he had only the tiniest white spot on his rump. Now, though, in true Appaloosa form, he has spots all over, so Picasso is fitting.”

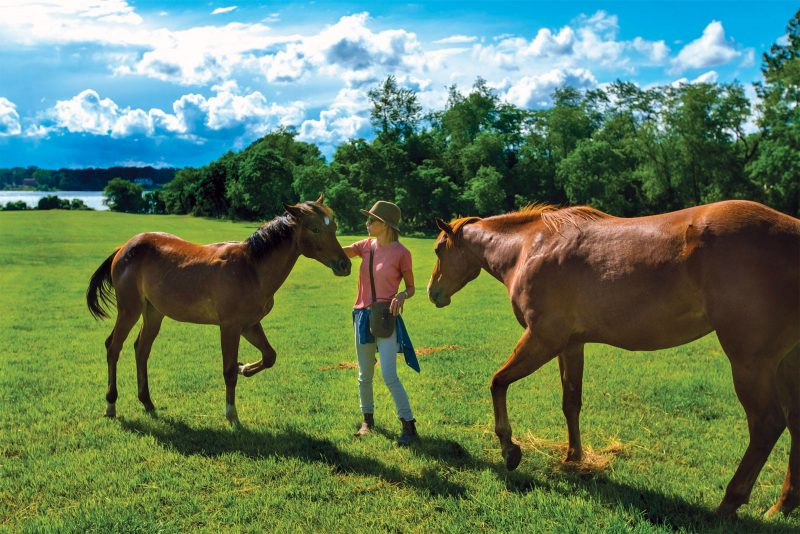

And Picasso is fitting in well with the herd at the riverside farm.

“It’s four boys now, with the addition of Picasso,” Veatch said. “Peanut is like his brother. Davinci plays the dad role, and there’s Uncle Thor. And Mona, well, we call her Queen.

“It’s fun watching Picasso; I feel like he brings a youthfulness. Peanut was a little quieter, more reserved with the older guys, but now Picasso and Peanut are constantly playing, running around. He has the elders to keep him in line, and it’s wonderful for me as a horse person. I can watch the herd teaching him. It’s great fun watching a horse mature and develop in a natural setting, so to speak, with large turnout and herd buddies to graze with through the days.”

With the herd safe and healthy, Veatch said that her husband has asked about her plans for both Mona Lisa and Picasso.

“I just want to give them a beautiful life, really,” she said. “When I first saw them in such horrid condition, I made up my mind that they would have a great life once I had rescued them. But I don't really have any plans. Mona is not able to be ridden, so she'll always just enjoy turnout and grooming. But Picasso, who knows? He may have a future ahead of him as far as competing, but I won’t be putting much pressure on him. I like just watching the guys enjoy being horses out there in the pasture.”

Not surprisingly, Veatch has more certainty about the health care her horses will receive. “It’s reassuring to know that when I take my horses to EMC, they are receiving the best care available,” she said. “Had I not gotten EMC involved with Mona’s delivery, I am certain that things would not have turned out as well as they have for either Mona or Picasso.”

Upon meeting Veatch at EMC, Estell remembered that she was struck by her generosity of spirit. “Not everyone is equipped or able to rescue a horse,” she said, “and it takes a special person who will adopt a mare who’s in foal, particularly when that foal might have problems and the mare is skittish.”

It’s precisely that generosity that prompts Veatch’s memories — and adds a sense of perspective. “I have to constantly stop myself from thinking about all the other horses. I just try to put my attention on these three that I was able to help. I feel really fortunate that I was able to save these horses. For me, it's very rewarding. I tell my husband all the time, ‘I promise they give me something back.’”

Epilogue: According to the Office of the State’s Attorney for Wicomico County, Maryland, the owner of the farm where the neglected horses were discovered was indicted on 16 felony counts of aggravated animal cruelty and 48 misdemeanor counts of animal abuse and neglect.

— Written by Juliet Crichton