Richard Turner reflects on five-decade career in polymer chemistry

After working more than three decades in industry, Richard Turner came to Virginia Tech in 2004 to serve as the first director of the Macromolecules and Interfaces Institute, now known as the Macromolecules Innovation Institute (MII).

Now, after 53 years as a polymer chemist, Turner is winding down his career.

Surrounded by colleagues, former students, friends, and family, Turner celebrated his retirement at the Inn at Virginia Tech on July 27. In June, the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors conferred the title of director emeritus of MII to Turner.

Destined for chemistry

Turner grew up in Old Hickory, Tennessee, a small suburb of Nashville originally built by chemical powerhouse DuPont to house workers for a World War I gunpowder plant.

His dad served as the village policeman, and Turner attended DuPont Elementary School and DuPont High School, so he said he was always destined to be a chemist.

At Tennessee Tech, Turner studied chemistry and played centerfield for the baseball team. Nearing graduation, he thought he’d take a job with, of course, DuPont, and play baseball on the side, but a professor persuaded him to stay for his master’s degree.

“He said, ‘I’ve been out to see you play baseball and you have a much better career as a chemist than a baseball player,’” Turner said.

That professor was Vernon Allen, and that conversation served as a pivotal moment to kickstart Turner’s career. Allen frequently collaborated with a polymer professor, George Butler, at the University of Florida. When Turner neared graduation at Tennessee Tech, Allen suggested that his pupil move to Gainesville to earn his Ph.D. under Butler. As a first-generation college student, this was a big new adventure for Turner.

He moved to Florida and started working in polymer synthesis, which he soon discovered to be his professional passion.

“That was really exciting,” Turner said. “Making things people haven’t made and seeing what the properties are is still something I think about at night and in the mornings when I come in.”

"Moving isn’t always easy, but sometimes it’s necessary"

Following his graduation from UF and postdoc work in Germany, Turner started his industry career.

He began at Xerox in Webster, New York, a town outside of Rochester, working on photoconducting polymers. His greatest achievement at Xerox was working out the process to make the Generation 3 organic photoconductor that the company commercialized.

After this project, Xerox started to de-emphasize polymers in its research, so Turner moved to Exxon in New Jersey.

“Exxon was pioneering new kinds of ion-containing polymers with Bob Lundberg, who was an industrial leader,” Turner said. “I worked on that for a year and a half and then worked on enhanced oil recovery. Oil prices were shooting up to unheard of record highs. I worked on water-soluble polymers for enhanced oil recovery, got a lot of patents … and then the price of oil dropped.”

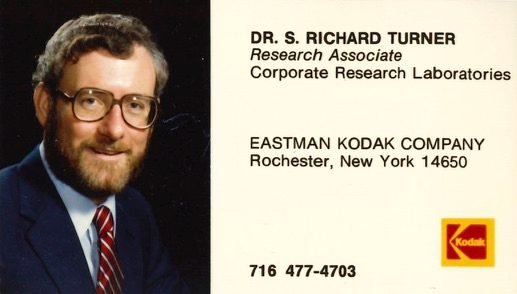

Turner packed up and moved back to Rochester to work for Kodak. Although initially working with a light-sensitive material known as photoresist, Kodak transferred him to a newly-formed corporate research lab. His new responsibilities were to work with dendrimers and hyperbranched polymers, but he also started recruiting on college campuses and began visiting Blacksburg.

But as Turner had learned throughout his career, industry changes quickly. Kodak dissolved the corporate research lab, and Turner transferred to Eastman Chemical Company in Kingsport, Tennessee, where he became an expert in amorphous polyesters.

“Moving isn’t always easy, but sometimes it’s necessary,” Turner said at his retirement celebration.

Teaching was always Turner’s goal, even as he wended his way across the eastern United States in various corporate research labs. He managed to satisfy that goal by teaching polymer chemistry as an adjunct professor at the University of Rochester for a decade. However, there weren’t many full-time polymer positions in academia. But in 2004, the perfect opportunity opened up not too far away in Southwest Virginia.

“A total scholar”

On a trip to Virginia Tech in 1986, Turner successfully recruited a Ph.D. student named Tim Long to work at Kodak. When Kodak dissolved their lab, Turner and Long both moved to Eastman in Kingsport.

Long eventually left Eastman and Turner to return to Virginia Tech as a chemistry professor, but the longtime colleagues would soon reunite.

Virginia Tech has a robust history in polymer science stretching back to the ’70s with faculty such as Jim McGrath, Garth Wilkes, and Tom Ward, who were titans in the polymer science field. But by the early 2000s, many of these efforts had fragmented.

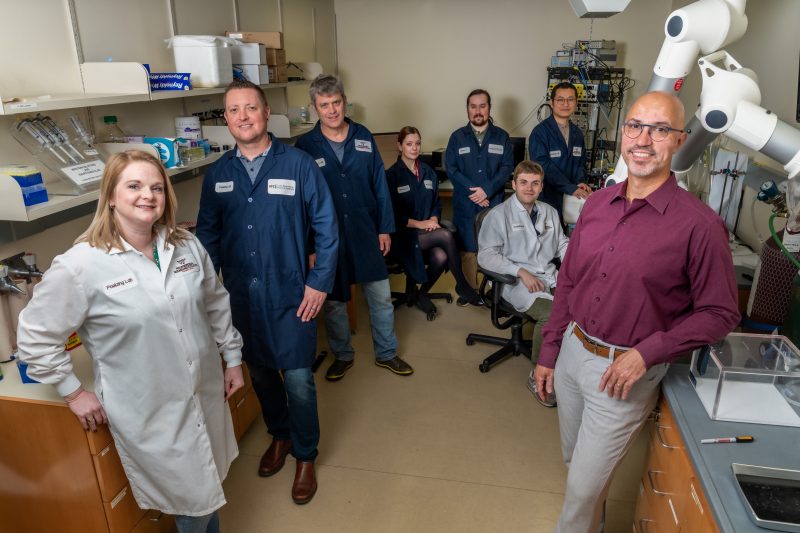

The university decided to coalesce five polymer groups into one, then known as the Macromolecules and Interfaces Institute. The five groups included: the Macromolecular Science and Engineering (MACR) Ph.D. program, the Center for Adhesion and Sealants Sciences, the Polymeric and Interfaces Laboratory, the Center for Composite Materials, and the Materials Research Institute.

Turner had interacted with faculty like McGrath, Wilkes, and Ward over the years at conferences, and he knew Virginia Tech from his recruiting trips. In 2004, Ward and Long came to Eastman to teach a short course and asked Turner to become the director of the new MII.

With his youngest child finishing high school and an itch to return to academia, Turner said yes and moved to Blacksburg.

Turner brought a fresh mindset from industry and got to work infusing the polymer programs with new ideas.

“The fun part about industry is that you work in teams,” Turner said. “They’re very multidisciplinary. You might have a chemical engineer, mechanical engineer, polymer chemist, lawyer, marketing person – all driving to get something into the marketplace from a discovery to development to customer sampling.”

Turner worked hard to bring in different perspectives from industry and universities to help diversify the discourse on polymers. Under his tenure, the MACR Ph.D. program grew and became an Interdisciplinary Graduate Education Program at Virginia Tech.

In 2012, Turner and Long brought the World Polymer Congress for the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, the largest polymer conference in the world, to Blacksburg. The conference was a huge success, bringing in upwards of 1,500 delegates from around the world.

But despite all the change during his 10-year run as director, perhaps his greatest accomplishment was keeping the status quo. Although MII had a growing reputation internationally, it was not widely recognized on campus.

“Two of the assistant vice presidents in the Office of VP of Research came down to see me and said we have these seven major institutes and you guys have to become a department center now,” Turner said. “I spent six months to get buy-in from deans to continue as a university institute.”

Long, who took over from Turner as director of MII in 2015, said this was no small feat.

“He was really steadfast at being present and pounding on the desk and saying how good MII is,” Long said. “He kept the ship running smoothly and reinforced the value of remaining focused on fundamental polymer science and engineering.

“Because of him, I’ve been able to take MII and look at opportunities in architecture, food science, 3D printing, and mechanical engineering, and it’s really paid big dividends. My job has been easy because I inherited a well-respected institute.”

Although Turner celebrated his retirement on July 27, he’s been winding down professional activities since ending his term as director of MII. He’s continued to work on grants and has a contract that runs until February, and his tenure as an editor of the journal Polymer will end later this year. But now that he’s director emeritus, he wants to stay involved on campus.

“It’s hard to quit,” Turner said. “If I could hit a golf ball straight, I’d probably do that, but I can’t. I’ll probably be skiing, golfing, and traveling a little more, but I don’t think I’ll quit reading the literature.”

For Long, his career has been entangled with Turner for the last three decades, so he’s known him in different capacities as an industry polymer scientist and director of MII.

“He worked on a lot of new polymer systems in industry that are still today being investigated and reported in the literature,” Long said. “He’s an absolutely great man in all respects and his passion is second to none. He’s a vocal, enthusiastic advocate for polymer science and engineering. When we brought him on as director of MII, it was a no brainer because he’s a total scholar.”