Keep calm and carry on: VTCRI scientists make first serotonin measurements in humans

Read Montague, Ph.D., discusses his work with Rosalyn Moran, Ph.D., and Terry Lohrenz, Ph.D., in a video conference.

Scientists at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute have begun to unravel how serotonin acts, based on data collected in a first-of-its-kind experiment that utilized electrochemical probes implanted into the brain of awake human beings.

The neurotransmitter serotonin is associated with mood and helps shape the decisions we make.

The readings were collected during brain surgery as patients played an investment game before receiving deep brain stimulation as a treatment to attempt to alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

The study, conducted in collaboration with Wake Forest School of Medicine, appears in the May issue of Neuropsychopharmacology, a publication in the Nature family of journals.

The research provides the first ever recordings of simultaneous sub-second fluctuations in dopamine and serotonin during active decision-making in a conscious human subject. The analysis provides new understanding of serotonin’s role in regulating human choice and how it operates alongside dopamine, a neurotransmitter long associated with reward and its reinforcement.

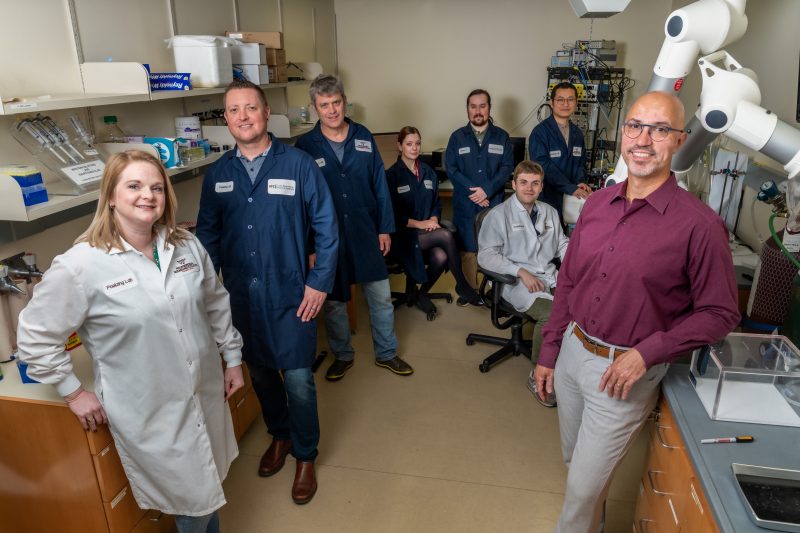

“This is the first clear evidence, in any species, that the serotonergic system acts as an opponent to dopamine signaling,” said Read Montague, the director of the VTCRI Human Neuroimaging Laboratory and the VTCRI Computational Psychiatry Unit and senior author on the paper. “If a person didn’t expect a positive outcome in the game but they received one, dopamine goes up while serotonin goes down.”

Montague is also a professor in the Department of Physics in Virginia Tech’s College of Science and in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine in the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine.

Ken Kishida, co-first author on the paper who was a research scientist at VTCRI at the time of data collection, worked directly with neurosurgeons at Wake Forest School of Medicine to take measurements of patients undergoing deep brain stimulation who volunteered to take part in the study.

Kishida, now an assistant professor in the department of physiology and pharmacology, as well as neurosurgery, at the Wake Forest School of Medicine, is developing this work with larger patient cohorts and increasingly realistic environments.

Subjects played a game related to gambling and, in this context, serotonin appears to act as a caution signal to prevent subjects from overreacting to an outcome. As the neurotransmitter is implicated in prevalent neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression, the researchers aim to uncover how the chemical aids humans in developing adaptive actions.

“We found that serotonin is highly active in the part of the brain that helps us to navigate bad outcomes in a way that ensures we don’t overreact to them,” said Rosalyn Moran, who is now a reader at the Institute for Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience in King’s College London. At the time of the date collection, Moran was an assistant professor at the VTCRI. Prior to her current position, she was a lecturer at the University of Bristol.

“Serotonin acts in a way that reminds us to pay attention and learn from bad things, and to promote behaviors that are less risk seeking but also less risk averse," Moran said. "When there’s an imbalance of serotonin, you might hide in a corner or run towards the fire, when you should really be doing something in between.”

The researchers refer to this middle-of-the-road behavior promotion as a “keep calm and carry on” motif. Here, serotonin appears to temper excitement over positive outcomes while softening the potential disappointment of negative outcomes. This process can go awry when the neurotransmitter levels aren’t in balance.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, more than 10 million adults in the United States suffered at least one major depressive episode. About half of those people take antidepressants, which primarily consist of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The drugs are designed to keep serotonin at elevated levels in a person’s brain by limiting its reabsorption.

“People take drugs to manipulate their serotonin when they have such low levels they can’t work or they may even be a suicide threat,” Montague said, noting that prior to his team’s work, the best measurement tool for serotonin was positron emission tomography (PET) scanning which measures one point every two minutes. “Now, we can measure a point every 100 milliseconds. It’s a completely different ball game in terms of the time regime that we’re in and the implications for understanding human behavior.”

The team will soon begin data collection at Carilion Clinic, through collaboration with Mark Witcher, a functional neurosurgeon. Witcher, who is also an author on the paper, became a collaborator on the project when he was the chief surgery resident at Wake Forest School of Medicine before becoming an attending physician at Carilion Clinic and assistant professor of surgery in the division of neurosurgery at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine.

Other contributors to this paper include Terry Lohrenz, a research assistant professor in the Montague laboratory at the VTCRI; Ignacio Saez, who was a postdoctoral researcher in the Montague laboratory at the VTCRI; Adrian W. Laxton, a neurosurgeon at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center; Stephen B. Tatter, a neurosurgeon at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center; the late Thomas L. Ellis, who was a neurosurgeon at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center; Paul E.M. Philips, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington; and Peter Dayan, director of the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit at University College London.

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship to Montague, as well as by the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and Wake Forest School of Medicine.