Graduate student preaches message of hope on Appalachian prosperity

Crystal Cook Marshall horizontal

Born in West Virginia and descended from coal miners, Crystal Cook Marshall knows all too well the stereotype of Appalachians as clannish and feuding, poor, and uneducated — the image of a region filled with moonshining hillbillies.

While working on a Ph.D. in the Department of Science and Technology in Society in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, Cook Marshall has amassed materials that give her hope. She said she believes Appalachia has untapped assets that can propel its “towns, people, and landscapes left for dead” into a new prosperity.

How did she come to believe in small towns' talents as a way to rise from Appalachia's history of "exploitation, labor uprisings, internal imperialism, externalized environmental costs, sacrifice zones," as she writes in a web essay?

By diving into more than a half-dozen years of research where she rubbed shoulders with mining engineers, nanotechnology researchers, organic farmers, welders, energy-sector executives, and others.

"You think Bavarians worry about being seen as the hillbillies of Germany when they cash the checks for Oktoberfest or liquor tourism?" she asked. "Our culture is part of our opportunity."

She recently stirred up comment as a guest on Craig Hammond’s "Radio Active" on WHIS radio in Bluefield, West Virginia, a weekday show named Best Talk Show in the state, with her ideas to spur economic development by focusing inward.

"How do you get innovation?" she asked the morning audience. "It’s not as complicated as people think. The reason that Silicon Valley has all this innovation is, first they do a tremendous amount of knowledge-sharing, and a lot of that is informal. Go into whatever coffeehouse is popular and you’ll run into someone who works at this other place, and we share ideas – it’s this rich culture and diversity."

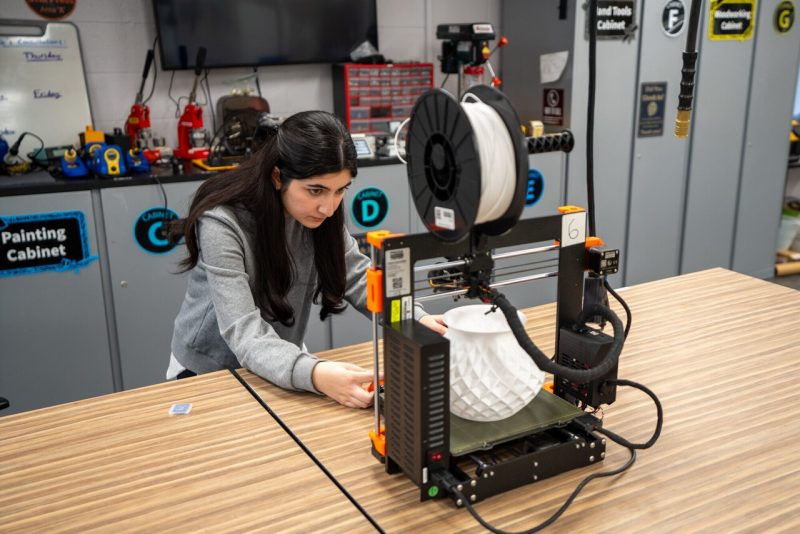

Take people with "heritage skills," such as logging with horses, together with those who know their way around a machine shop or a welder’s arc, and join them in the same room with university high-tech researchers. Then step back and watch the magic happen, she said.

Along with preparing to devote this summer to writing her dissertation, Cook Marshall is trying to get a project up and running in Bluefield, where she grew up. Teamed with two ex-military veterans running an organic farming cooperative in the heart of coal country, they have developed a plan.

They envision a bricks-and-mortar project involving an 88,000-square-foot former school building near downtown, which a local carpenter and woodworker, Lawrence Calfee, owns. They're looking for investors to fund an operation that will include the production of mead and moonshine.

"I’ve had a chance to work with my husband, who was one of the first sustainable organic farmers in the I-77 corridor of North Carolina," she said, referring to the couple's property in Union Grove. "I’ve immersed myself in it and walked the walk. The Bluefield project would give a shot in the arm to agricultural economic-sector growth in the region."

She preaches a message of prosperity based on economic sectors "where the jobs can’t be automated away," which she discusses in-depth in an interview with Virginia Tech's web series Save Our Towns. (The transcript is posted on the web, and her "expert tip" can be seen starting at marker 6:34 in the episode of Save Our Towns below.)

In her usual lyrically complex phrasing, she writes of her hometown Bluefield's identity as “a hamlet that exploded during the reign of King Coal,” with a population that included “white mountain folk and sharecropper, African American and southern and Eastern European immigrant music, houses of worship, foods, businesses, socialites, strong bosses, organized crime, union organizers, and workers” – so much so that it was once deemed “Little New York.” The town’s fall into economic decline in the decades that followed was especially poignant.

So how did the Bluefield morning-show audience react to her ideas?

“Crystal not only identified the challenges facing our region, she clearly outlined strategies to meet those challenges,” said Hammond, the radio host who is also a former mayor. “The solutions to our problems were hiding in plain sight.”