A prescription for the future

Just over a decade ago, Virginia Tech teamed up with Carilion Clinic in Roanoke to lay the foundation for a medical school that would not only produce new physicians, but ensure that those physicians would become leaders equipped to practice in the changing world of medicine.

How do educators train medical professionals to care for people in a future that is yet unknown?

Just over a decade ago, Virginia Tech teamed up with Carilion Clinic in Roanoke to tackle that challenge, laying the foundation for a medical school that would not only produce new physicians, but ensure that those physicians would become thought leaders, equipped to practice in and lead the changing world of medicine.

In the 14 years since the first class stepped through the doors, the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine has established itself as a prominent destination for medical students seeking proven, innovative, real world learning experiences that incorporate valuable opportunities for research and discovery.

Those experiences have inspired numerous students to return to the region to begin their medical careers, a valuable secondary benefit for the greater Southwest Virginia community.

A brief medical history

In the early 2000s, the idea of a research university partnering with a regional health system to develop a medical school in a primarily rural region seemed unorthodox. No new medical schools had been developed in the U.S. for more than two decades.

But as the plan took shape, the benefits came into focus.

The Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine sprang from a vision inspired by the late Charles W. Steger, Virginia Tech’s 15th president, and the late Ed Murphy, then Carilion Clinic CEO, along with industry and community leaders who were committed to investing in medical education and biomedical research in Roanoke. At its core: serving the growing health care needs in the community and across the commonwealth.

Recognizing the statewide implications for the project, the team steering the process collaborated with Virginia officials from concept to execution. And on Jan. 3, 2007, when they officially announced that Roanoke would indeed become home for a new medical school, they were accompanied by then Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine.

According to Lee Learman, current dean of the medical school, building community remains an integral part of the school.

“When I interviewed for this position, I could tell that something very special was happening in Roanoke. There was so clearly an alignment between Virginia Tech and Carilion Clinic on the importance of building a school and serving the community,” Learman said. “Since arriving, we’ve continued to innovate our curriculum in service of our mission to train future physician leaders who work to improve the health of patients and communities.”

Learman is the second dean of the medical school, following Cynda Johnson, who was named the founding dean in 2008 following a nationwide search.

In 2014, the first class graduated from the new school. And new graduates have joined the ranks of the school’s alumni every year since, taking the skills they’ve acquired to some of the most prestigious health systems in the country, where they are now ambassadors for the school. From 2014-24, more than 99 percent of students matched into residencies with more than 95 percent going to their first-choice specialty. Alumni have matched in 36 states plus Washington, D.C.

But in the early days of planning and organizing, such successes were simply goals without any guarantees.

In 2009, when the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine received preliminary accreditation from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), greenlighting recruitment of the first students, there was a calculated risk for those individuals pinning their dreams of becoming a doctor on the brand-new school.

It was one of four new medical education facilities adding students that year, and Johnson admitted to a great deal of anxiety leading the formation of the school and inviting the first class. Would anyone enroll, she wondered?

“The first thing we did was crystalize what would make the school distinctive and represent the two partners. For Virginia Tech, the most important thing was to be research intensive. For Carilion, it was a community focus with small classes so students could do their clinical rotations locally,” Johnson said. “We wanted to make sure the pillars were in place and that we wouldn’t wander from them as some other medical schools have done. We stuck by them and sought out students who would subscribe to our values.”

Johnson’s fears were assuaged when about 1,100 applied to join the inaugural class of 40 students.

“What you must remember is that we didn’t have full accreditation yet from the LCME or the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. That would come later — before they graduated,” said Dan Harrington, former vice dean. “So those students were pioneers. They were coming in with an incredible amount of trust that we would do what we said we would do and that the school would be successful.”

In succeeding years, the school’s reputation for excellence has grown, attracting applications from the most prestigious undergraduate institutions, nationally and internationally. Just 51 students from a pool of 6,184 applicants were accepted into the Class of 2027, making the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine one of the most selective medical schools in the country.

Differential diagnosis

The 40 alumni who made up the charter class would help pilot a new curriculum, which unlike that at many larger medical schools emphasized problem-based learning.

“We really had an incredible class. They kept everyone on their toes. If something wasn’t going right, they would let you know. We had weekly meetings with them from the beginning,” Harrington said. “It was like you were building a plane while you were flying it. You would not be able to change curriculum so quickly now that it is established, but back then, students came to us with suggestions, and we could adjust.”

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered approach to education. Students learn about a specific subject by working together to solve a problem. Understanding and solving the problem drives motivation and learning. At the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, students met weekly in small groups to independently investigate and propose treatment for a medical scenario.

Problem-based learning proved effective in helping students think beyond the textbook and develop a patient-centered approach.

“The PBL classes were unique and immediately impactful. Many medical schools have started doing something similar now because it is very effective in teaching you to think clinically and work within a team to treat a medical issue,” said Raeva Malik, who came to the medical school from a suburb of Washington, D.C. “The part that was the best was getting to meet with the actual patient at the end of the week and having the opportunity to discuss their case.”

Problem-based learning encourages students to analyze a problem, determine what they need to learn and where they can find the tools required to define a solution, and to evaluate possible solutions. Eventually, the students solve the problem — in this case a patient diagnosis and plan for care — and report on their results.

“With the small-group work and the pass-fail grading, it made for a very positive and supportive learning environment,” said alumnus Matt Joy. “We were much more concerned about making sure everyone had the knowledge to succeed rather than worrying about beating out each other for class ranking as happens at some larger medical schools.”

Joy completed an undergraduate degree at the University of Southern California and was pursuing a music career in Los Angeles before changing his path to medicine. As a more experienced and married student, he took on a leadership role, hosting regular get-togethers for classmates. Joy was elected class president, a role he held throughout his time at the school.

Additionally, the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine dedicates more than 1,200 hours of its curriculum to research. The goal: developing scientist physicians.

All students are expected to conduct original, hypothesis-driven research of sufficient scope to span their time at the school. Each student is allotted funding in years two through four for research supplies.

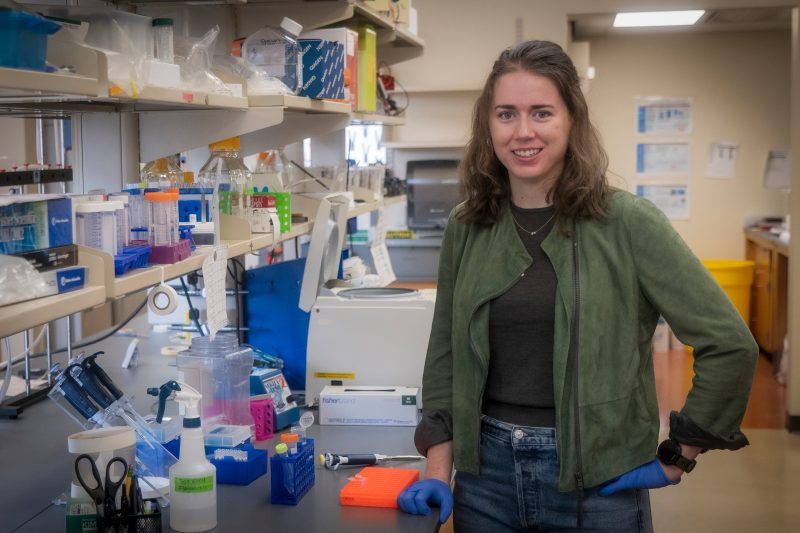

“There are so many skills and mindsets that relate directly to clinical medicine that you develop through research,” said Ellen Shrontz. “Aside from just understanding how to read research articles and approaching scientific topics in a better way, it encourages you to tackle difficult problems, shows you it’s OK to reach out for help and teaches you to persevere through challenges.”

Shrontz was one of nine students to receive a Letter of Distinction for her research in 2023, and she presented it at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine’s annual Medical Student Research Symposium.

“While some schools offer tracks in research or health systems science, we require all our students to successfully complete these curricular domains,” Learman said. “In addition to becoming scientist physicians, we are developing system citizens who understand how health care systems operate and how to improve health equity. Because the knowledge and skills needed for evidence-based practice change rapidly, it’s equally important that our students become master adaptive learners who excel at self-directed lifelong learning.”

Beyond the classroom, every milestone established new traditions. The White Coat Ceremony, Match Day, and graduation all set the standard for future classes. Johnson fondly remembered picking out the colors for the graduation hoods: maroon for Virginia Tech, blue for Carilion Clinic, and green for medicine. Even the required national testing for medical students took on added importance.

“One significant moment when I knew we had something special was during the [United States Medical Licensing Examination] STEP 1 process. It is the first major standardized testing in medical school at the end of the second year, and it goes a long way to determining if you will become a doctor and how you will do in the residency match process,” said Don Vile, who attended Harvard University for his undergraduate degree and worked in software engineering before attending the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. “We performed extremely well as a class with one of the highest average scores in the country. It served as confirmation that we were on the right path and was one of the early signs the class and the school were going to be successful.”

A positive prognosis

As the members of the Class of 2014 matriculated to residencies and fellowships and continued into their specialties, the school where they had begun their medical training also evolved.

On July 1, 2018, it became an official college of Virginia Tech, and a year later, Learman joined the school as the second dean.

Increasing enrollment among Virginia residents and expanding graduate medical education positions, also known as residencies and fellowships, in the region in response to growing physician shortages, are the top priorities for the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine (VTCSOM).

A 2020 study by the Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association found that about 32 percent of physicians attending medical school in the commonwealth remain in Virginia to work, while more than 64 percent who attend medical school and their graduate medical education positions in Virginia stay.

“We are seeking support from the commonwealth to lower financial barriers for in-state students attending VTCSOM” Learman said. “Right now, many Virginians who get accepted into medical schools must leave the state for that education. As we grow our enrollment and seek support for in-state students, we expect more of them will stay in Virginia and serve our communities as physicians.”

Carter Gottschalk, the Class of 2026 president, grew up close to Roanoke, graduating from Staunton River High School in 2016. He attended Virginia Western Community College and completed his bachelor’s degree at Virginia Tech before entering medical school.

“I remember hearing about a medical school opening in Roanoke, and I thought how amazing it was that we were getting a center for medical education and research,” he said. “I would have picked VTCSOM even if it wasn’t in Roanoke. The mission of the school truly resonated with me, and I appreciated how well-supported the students I met with were. The fact that VTCSOM was local was just the cherry on top of what appealed to me here.”

As the school develops enrollment growth proposals, it also is planning an expansion that will more than double its physical size with a new building in Roanoke’s Innovation District. Currently, the school shares a building with Virginia Tech’s Fralin Biomedical Institute at VTC, and the proposed building site is nearby. The Virginia General Assembly recently approved $9 million in initial planning funds for the new facility and renovation of the vacated space to support further growth for the institute.

“The new building will be an essential component to increasing our class sizes and recruiting more faculty to instruct the students. The new space will be built to accommodate up to 100 students per class, with an expected opening in 2028,” Learman said. “We see this as a critical evolution but will not forget what has made us distinct. The special connection our students make with faculty and with each other in small groups is a hallmark of what we do. When we think about growth, we are being very deliberate in making sure we maintain what makes us great.”

Back to where it began

“When I was giving talks about the new medical school in the early years, community members would always ask if the students would all stay,” said Cynda Johnson, founding dean of the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. “I had to explain how residencies and fellowships work and that most would leave. I said some will come back and others will go elsewhere, but they will all carry our message. My real dream, though, was that the next generation of faculty at our school would be our graduates. And that is coming true.”

One of the returning physicians hailed from the inaugural class. Matt Joy was the first plastic surgery residency graduate from the Carilion Clinic-Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine program and, following a fellowship in reconstructive microsurgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he returned to practice at Carilion. Joy also teaches as an assistant professor of surgery. His feelings about the community were cemented early in his time at the school and stuck with him as he developed career plans.

“I remember we had a reception where dozens of well-known and involved members of the community came to introduce us to Roanoke and help us and our spouses make important connections. The mayor of Roanoke also visited and passed out certificates welcoming us,” he said. “To have that kind of roll out to medical school students was exceptional. It was very telling of the interest and gratitude the community had for us to come here and to see us succeed.”

Where are they now?

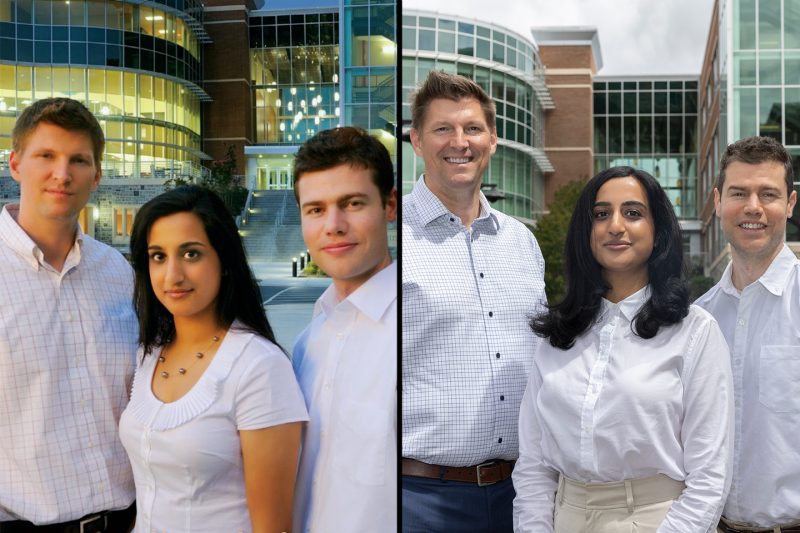

When the new Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine opened in 2010, Virginia Tech Magazine celebrated the addition with a story about the school. The cover featured three of the first students: Don Vile, Raeva Malik, and Robert Brown.

Vile returned to Roanoke in 2020 after a residency in internal medicine and a fellowship in hematology and oncology from Wake Forest Medical School. He now is an oncologist at Blue Ridge Cancer Care, where as a student he performed clinical studies with many of the physicians he now calls colleagues. He also serves as an assistant professor of internal medicine.

“More than anything, I feel a great deal of gratitude for the investment the school and the community made in the charter class. I think all my classmates have gone on to become great successes,” he said. “The reason many of us have returned is so that we can give back to the community and the school that helped get us where we are today.”

While Malik has not come back to work in Roanoke, she has maintained close relationships with many of her charter classmates—one in particular. Malik and Shervin Mirshahi started dating near the end of their medical school education and continued through their residencies, Malik in internal medicine at George Washington University and Mirshahi in radiology at Virginia Commonwealth University.

They were married in 2018 and have a son who is nearly a year old. Both now practice and teach at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, where Malik is a hospitalist and Mirshahi is an interventional/endovascular surgical neuroradiologist.

“Roanoke and the school hold a special place in our hearts,” Malik said. “We love to come back when we can to see the places where we first started dating. It’s also great to be able to catch up with classmates who have returned.”

Brown is one of the first eight members of the charter class who are practicing in Roanoke. He completed a combined residency in internal and emergency medicine as well as a fellowship in critical care at the University of Maryland Medical School in Baltimore. He said that seeing his classmates and friends return and support the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine was the best recruitment tool possible.

“There are outstanding schools and medical centers across the country, but many of them are very established and in metropolitan areas, where it is hard to see your impact. It’s unique here because we are developing something in an area where there is a clear need,” Brown said. “As graduates, we are in that lucky position that we can stay and be part of building something amazing.”

Defining moment

Sadly, a defining moment for the first class at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine involved the loss of one of its own. Caroline Osborne was diagnosed with cancer during her third year of medical school and died in 2014.

Osborne’s classmates contributed patches from their white coats to create a memorial quilt that is a centerpiece for a remembrance wall in the school. Also, they have supported a memorial scholarship in her name.

“Caroline wasn’t just anyone. She was among the smartest in the class and a true leader. It was heartbreaking to all of us when she was diagnosed,” classmate Robert Brown said. “To the end, she gave of herself to help advance medical knowledge. Caroline really represents the spirit of this class.”