'Hidden in Plain Sight' exhibit shines a light on the history of slavery in Charleston

An exhibit highlights research into the hidden history behind the romanticized representation and perception of Charleston, South Carolina.

The sweeping porches, immaculate grounds, and luxurious spaces of historic mansions and plantations in Charleston, South Carolina, are popular backdrops for modern weddings and vacations. But behind this beauty and romanticized history of plantation life hides the fact that Charleston, once the wealthiest city in the 13 American colonies, was built on the profits from trading enslaved people and from the cotton, indigo, and rice enslaved workers produced.

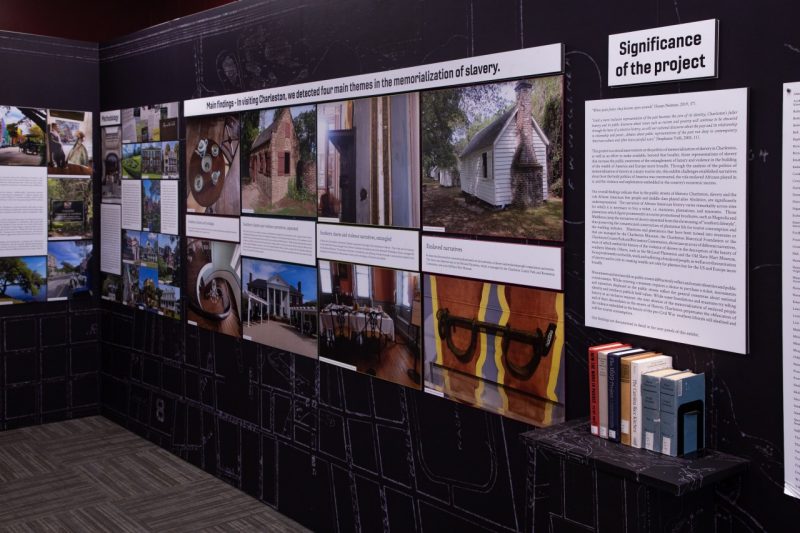

The exhibit "Hidden in Plain Sight: The Politics of Memorialization of Slavery in Charleston, S.C.," on the second floor of Newman Library, shines a light on the history of slavery in Charleston. The interactive exhibit, based on research by Laura Zanotti, political science professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, and Zuleka Woods, graduate research assistant for the Center for Refugee, Migrant, and Displacement Studies, examines themes in the memorialization and representations of slavery in Charleston’s public spaces including Southern charm and nostalgia, Southern charm and violence, and enslaved narratives.

“This project started as a result of a casual conversation with my Ph.D. student Zuleka Woods,” said Zanotti. “We had both independently visited Charleston as tourists, and we both were puzzled by how the memory of slavery is almost absent in the streets of historic Charleston and by how plantations are still marketed as wedding venues. We decided to dig deeper.”

With the support from Dean Emeritus Jerry Niles of Virginia Tech’s College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences and the college’s Juneteenth Scholars Program, Woods and Zanotti spent four days visiting mansions, museums, and plantations in Charleston — much like a tourist would but with a different lens.

“Because this research started as the result of our discomfort about how the story of slavery is told, or not told, in public spaces, we felt that its findings should first and foremost be an intervention in public memory,” said Zanotti. “Also, we felt that our message needed to be documented through pictures, showing the contrast between the beauty of the mansions and the luxurious lifestyles of their owners, and the toiling and sufferings of those who made that lifestyle possible.”

Woods and Zanotti partnered with Scott Fralin, University Libraries’ exhibit curator and learning environments librarian, to shape the research into a free standing visually and intellectually striking exhibit.

“I knew it was an important story that should be told, but it took a while to process and synthesize the raw data they collected on their research trip,” said Fralin. “The researchers and I had many meetings where we talked about the content and how to best tell the story they were trying to present. I made suggestions on how to shape it into a story more suitable for an exhibit format, and they patiently explained their arguments and reasoning to me. In the end, we had a set of text and photos that at the same time presented their research well and told a story that works as an exhibit.”

For exhibit viewers, it can be a much easier way to learn about a complicated or difficult subject.

“The visual nature of an exhibit draws people in and helps reinforce the researcher’s points in a way not possible in a paper or article,” said Fralin. “In an exhibit, the text is concise and to the point, working with visual and physical elements to make a point via a holistic experience. Being in a purposefully designed space can be more memorable and impactful to visitors than reading a paper.”

“By sharing our findings in a visual exhibit, we essentially could share our experience in a play-by-play fashion,” said Woods. “The visual exhibit brings people into the field with us and along the way as we collected the information for this project. Although we still plan to continue to share the findings from this project in other ways, the visual exhibit is by far the most inclusive and engaging for many audiences.”

According to Zanotti, the work aims to make an impact on public memories that contribute to national identity and to shift narratives about race, racism, and the making of America that has been clouded by a selective memorialization process.

Woods said being able to share it in a public space like Newman Library is important.

“The university plays a key role in the development and education of the community,” said Woods. “Newman Library is the heart of research in and around Virginia Tech. The exhibit’s purpose is to start a discussion surrounding the representation of slavery in public spaces and more broadly the politics of memory. Newman Library is an ideal location for not only housing these discussions but also continuing to provide resources to the Virginia Tech community to engage in these discussions.”

Community members can visit the exhibit in Newman Library during library hours through the summer. Zanotti, Woods, and Fralin also built an online exhibit featuring the research.

Zanotti and Woods hope to conduct similar research in other locations in the American South.

“We hope to be able to attract more funding to expand our research on public memory to different locations in the South,” said Zanotti. “Maybe Savannah will be next?”

.jpeg.transform/m-medium/image.jpeg)