Phillip Sponenberg retires after 42 years of helping veterinary college, its students thrive

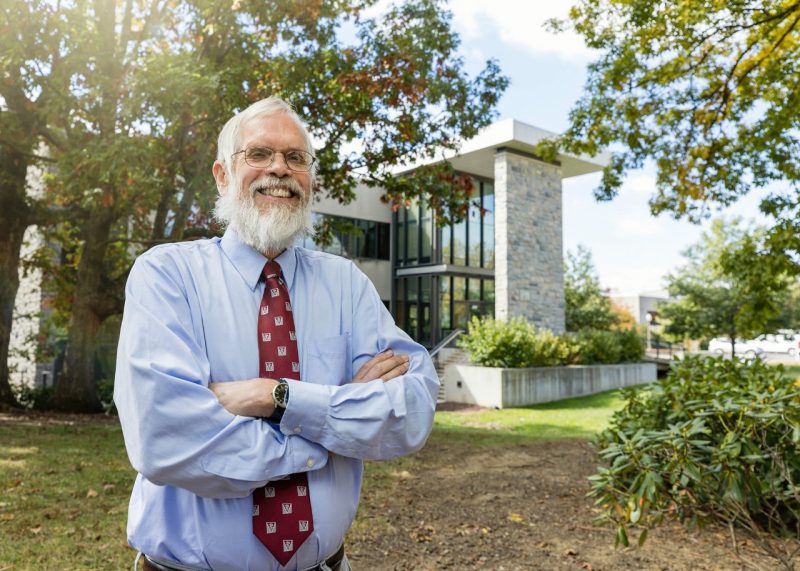

If the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine commissioned a monument with the likenesses of its most influential people, surely Phillip Sponenberg’s distinctive white beard would be chiseled into granite.

Sponenberg arrived as the veterinary college was sprouting out of the pastures on the southwest side of the Virginia Tech campus in 1981. This past summer, after 42 years of mentoring multiple generations of veterinarians and undertaking internationally acclaimed genetic research that has identified and conserved rare livestock breeds, Sponenberg retired from the veterinary college.

Sponenberg has been present at every veterinary college commencement since the first one in 1984 and has attended every university graduation since he arrived on campus. Graduates from five different decades extol Sponenberg as a beloved professor who consistently dispensed knowledge, wisdom, and kindness.

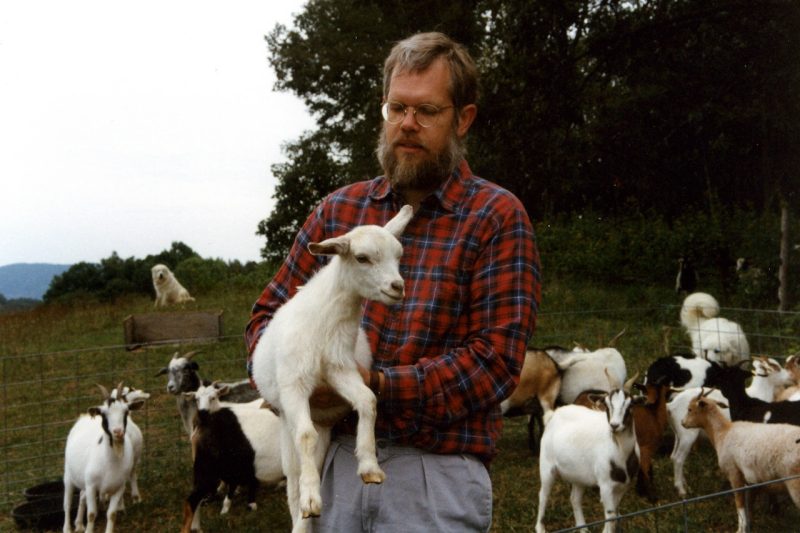

“I learned so much from you, and I went on to have some milking goats when I eventually got a farm, years and years later — Nigerian dwarfs!,” June Chandler Mergi, DVM '85, owner of a veterinary practice in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, wrote in a congratulatory e-mail for Sponenberg’s retirement. “I named two of them Sponen and Berg, if you can believe it! That's the impact you made on a young mind.”

Starting at the ground floor of a new veterinary college enabled Sponenberg to cut out a niche in which he thrived and never seriously considered leaving.

“It’s been really, really good for me because what I do now is not what a veterinary college would be looking for now,” said Sponenberg, professor of pathology and genetics. “I was able to cobble together my interests. I probably could not have done that anywhere else, because they would have been looking for somebody to fill a slot that someone else had vacated.”

The early years of the veterinary college were uncertain times, as the college faced political and funding challenges.

“That was actually an interesting time because a very, very few of us actually kept the place going,” Sponenberg said. “When I started here, you could ask anybody to do anything, and they would say yes. I have taught equine palpation labs on 15 minutes notice.”

The rural, mountainous nature of western Virginia was attractive to Sponenberg, a Texas native, and his wife, Torsten, as was Blacksburg itself, then much smaller than it is today.

“We like living in small towns, and at that time, Blacksburg was quite small,” Phillip Sponenberg said. “When we first arrived, we kept driving through town and missing it. We’d drive through and it was like, ‘Where was it?’ We’d turn around and go back and ask ‘Where was it?’ So, we finally figured out it wasn’t very big.”

The Sponenbergs would eventually buy “100 vertical acres” in western Montgomery County for their home site and ranch, which today pastures a herd of Tennessee fainting goats, guard dogs imported from Bulgaria to protect them, and some chickens to entertain both the dogs and the Sponenbergs.

Tennessee fainting goats – they don’t really faint, but fall over from a genetic muscular condition that limits their mobility and makes them easier to keep inside enclosures – became rare by the 1980s, but their numbers have recovered since.

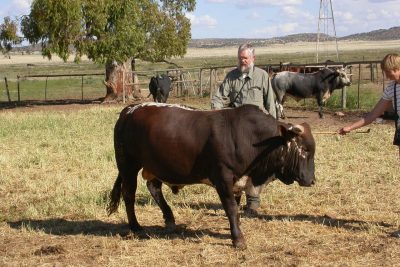

The fainting goats are but one of many livestock breeds that Sponenberg has helped identify and conserve, work that goes on for him past his retirement from the veterinary college through The Livestock Conservancy, for which he serves as technical advisor. The organization, formerly called the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, gave him its Special Service Award in 1997 and named an annual award after him in 2002.

Descendants of European livestock brought to the Americas in colonial times often contain genetic linkages to breeds that are no longer found in Europe or in large populations in the Americas.

Sponenberg, a recipient of the Keeper of the Flame Award from the American Indian Horse Registry in 2007, is sometimes surprised when his research finds an isolated, genetically unique population, such as wild horses at Fort Polk in Louisiana that were found two years ago to be genetically similar to Spanish breeds found in Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela but not those elsewhere in the U.S.

“The conservation work continues,” said Sponenberg. “We were down in Mississippi getting genetic samples in the 90-degree heat earlier this summer. We found an old Spanish sheep breed that's quite resistant to the humid tropics. And we're going to need that as the climate changes.”

The 2019 Alumni Award for Excellence in International Outreach recipient at Virginia Tech, Sponenberg combines his research work with a deep love for Hispanic and Latino culture, as much of it has taken place in Latin American nations.

“It turns out that in the history of European contact in North America, the Spaniards ran everything up to and through the Carolinas, and clearly everything west of the Mississippi,” said Sponenberg, who speaks fluent Spanish. “That’s all gone. The genetic connection is still there, but the cultural connection is not. Because of the Civil War, there’s this abrupt break in the 1860s. We’ve had these species since well before 1860, and back then settlers may have realized they got them from the Choctaw Indians who got them from the Spaniards. But then the war disrupted that knowledge due to losses of people and oral traditions.”

Sponenberg’s publication output has been voluminous, with authorship or co-authorship of 17 books, 33 chapters, 127 refereed papers, 82 abstracts, and 448 papers for a lay or extension audience. He has often been called upon as a podcast guest to discuss various breeds of animals, such as a talk about geese and turkeys in November 2022 on "the Academic Minute" for the American Association of Colleges and Universities

“I feel like I’m discovering something that’s out there, and it’s waiting to be discovered, so all we have to do is manage to find it,” Sponenberg said. “That removes any sense of personal ownership. That’s probably healthy for all of us, but the work still needs to be done.”

Students often credit Sponenberg for the description of veterinary medicine as the “Swiss Army knife of medical professions,” though Sponenberg himself says someone else coined that phrase. Sponenberg sees veterinarians as indispensable in efforts to improve not only animal health, but that of humans and the environment.

“Veterinarians are essential because our education actually involves a different thought process than physicians,” said Sponenberg, inducted into the Sigma Xi scientific honor society and the Phi Zeta veterinary honor society. “That really surprises people, but when you work around physicians and you work around veterinarians, you can see that they're actually doing things differently and thinking differently.

“We, as veterinarians, have to look at the entire environment and the entire system under which the disease is expressed in the animal’s life. So, it's really a holistic approach. For every disease there’s an immediate intervention. But there’s also a long-term intervention, a management change or environmental change, that can prevent the whole thing.”

Sponenberg, who did his undergraduate and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine studies at Texas A&M and earned a Ph.D. at Cornell University during the 1970s, said veterinary students at Virginia Tech are different because “on average, historically, they have had more direct hands-on experience and more direct decision-making experience” than students at many other veterinary colleges.

His former students recall many humorous and poignant moments with Sponenberg.

Among those sent in by veterinary college alumni during a recent call to share memories ahead of the Connect 2023 veterinary college alumni weekend were “the night we had to do a necropsy on a yak” and Sponenberg being a rare person who “knows all the words to Ol’ Mister Johnny Trebek.”

Many veterinary college alumni remember Sponenberg for his intellect, teaching skill and kindness.

“I still tell people about little quips and stories he told in class and those stories and quips really helped me remember the material,” said Shannon Subasi, DVM ’13, an equine veterinarian in Los Alamos, New Mexico. “I always appreciated his quiet humor and I am impressed to find out how long he was involved at the school. We were lucky to have him and I wish him much enjoyment in this new chapter of his life.”

“Dr. Sponenberg was a role model for me of how to treat others in the workplace - kind and sensitive, while being an excellent diagnostician,” said Tracy Brown, DVM '95, a North Carolina equine veterinarian. “Upon meeting Dr. Sponenberg, I was intimidated by his quick brilliance, but quickly found that I loved his class and rotations because he was a skilled teacher. He is caring and thoughtful while demonstrating how to be thorough veterinarians.”

Mario Dance, DVM '90, the first Black man to graduate the veterinary college and now a Richmond-area veterinarian and retired biomedical researcher at Virginia Commonwealth University, recalled how Sponenberg “made me feel welcomed and supported and made me feel like I was more than a number in a faceless crowd.”

Dance, founder of Catholic Evangelical Missionary People of Color Grant, added that Sponenberg, long active in the Christian Veterinary Fellowship, affirmed his faith and “gave me confidence that being a good veterinarian was not only possible but also a work of grace for me and for others.”

Sponenberg’s influence will continue beyond his retirement at the veterinary college, as it has for former students who have already built decades-long careers themselves.

“Dr. Phil is one of the top three men in my life who molded and shaped me as a student, as a practitioner, and as a human,” wrote Bruce Bowman '83, DVM '87, who led a mixed animal practice in the Shenandoah Valley for 25 years, served as a Virginia state agriculture department veterinarian for 10 years, and continues to consult in livestock and poultry diseases with serious economic impact. “I know my career story would be considerably different if it wasn’t for his over-the-top effort to ensure that I succeeded. I will be eternally grateful.”