Cross country, fast food, and authenticity: The journey of engineer Lianne Lami

Lianne Lami came to Blacksburg from Pennsylvania because Virginia Tech was more affordable than her in-state engineering schools in Pennsylvania were at the time and because the mountain scenery made an excellent backdrop for a cross-country runner. She worked to pay her way through school, mixing her employment between industrial co-ops and campus jobs.

She excelled in her classes and even tutored her peers, one of whom was football all-star Bruce Smith. Despite strong academics, she struggled with the balance of paying her way through school by holding down a job while carrying a full-time course load.

“There were a couple times when I didn’t think I was going to make ends meet and would have to leave,” Lami said. “Pell grants went away halfway through one of my terms. The co-op program was the way I was able to stay in school.”

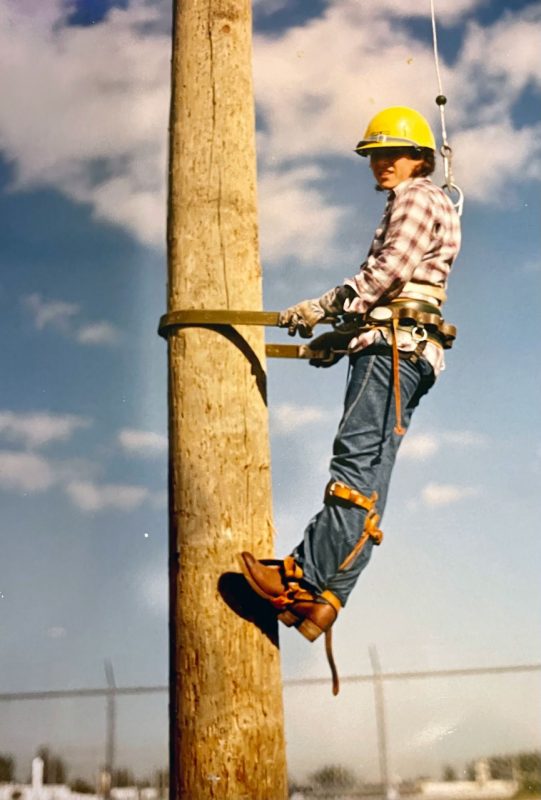

Over five years, her co-op appointments included stints with utility companies and manufacturing. The direct industry work gave her insights into professional life and helped her understand how to build a network. It also helped her understand what she definitely didn’t want to do. By the time she finished her degree in mechanical engineering in 1988 — racking up hundreds of miles on the cross-country team along the way — she had a clear trajectory.

The tenacity that got her through college paid off when she decided to pursue her professional engineer’s license. A rigorously hard test, she struggled with missed questions that seemed to be slanted more toward the academic world than the practical one.

“I took the test five times and didn’t pass,” she said. “You only get six attempts.”

Convinced that the test had been written for a different type of engineer than she had become, she decided not to make the last attempt. As she began exploring her options for what she might do instead of professional engineering, she had a conversation with a female civil engineer who owned a business north of Richmond.

“You’ve got to take the test again,” she told Lami.

The advice paid off, and she passed the test.

'What do you normally do?'

As she was starting her career, she hit an early roadblock. Working in construction certification, she refused to certify a building that wasn’t fully ready for use, despite political pressure to do so. When the blame rolled back on her, she resigned.

“I thought I did the right thing, but it wasn’t welcomed,” she said. “That was a big change in my career. The economy was tepid, but I did some project management at Habitat for Humanity and worked as a mechanical contractor. To pay the mortgage, even though I had an engineer’s license, I was working at a Taco Bell down the street from where I lived.”

One evening between the lunch and dinner shifts, she was cleaning tables and emptying garbage when a man in a suit walked in and ordered. She brought out his food, and he looked at her quizzically.

“What do you normally do?” he asked.

He commended her obvious work ethic, particularly the excellence with which she was conducting mundane tasks. Lami was caught somewhat off-guard by the question but answered honestly.

“Actually, I’m an engineer,” she said. “I’m in between jobs.”

That customer was Wayne Verlander, a regional manager at Honeywell and 1977 electrical engineering graduate from Virginia Tech. After a short discussion about her background, he invited her to come to his Richmond office. He couldn’t guarantee her a job, but he directed her to an interview.

She got the job. Her chance meeting with Verlander queued up a return to engineering, rebooting her engineering trajectory and putting her back in the field of energy. She spent most of the next decade helping large companies unify the energy grid and its resources, with a tight focus on efficiency. Working for both utility companies and those selling resources, she saw the full landscape of the energy economy, making steady progress with new opportunities.

A company named after Nanny’s favorite game

After a little more than a decade in energy engineering, Lami formally launched her own company: Bocci Engineering. The catalyst for that decision was the end of Enron, where she was employed when it notoriously failed in 2001. Despite the public downfall of that company, Lami’s experience there proved vital in her path to business ownership. Working at Enron in an entrepreneurial capacity, she left with a notable set of skills centered on understanding and navigating the fuel economy.

Bocci was named after a backyard game that involves throwing balls at a common target. Lami had often played the game with her grandmother, better known as “Nanny.” Nanny was a cutthroat competitor in the game, but also a warm and mothering figure in Lami’s life. At large family gatherings, following a meal together, the family would always wind up on the field with bocci balls in hand.

“If I called the company by my name, it would always be about me,” Lami said. “Bocci brings everyone together, so that’s why I chose it.”

She incorporated Bocci in 2007, hiring 17 employees by 2008. She also got ahead of the game for remote work, leaving a dedicated building in 2012 to deploy all her employees in a coast-to-coast, work-from-home environment.

“It wasn’t easy at first,” she said. “People would look at our company and think we weren’t the real thing because we didn’t have an office. The whole demeanor of a small company being a substantial innovative resource while working from home, not having a physical office space, changed with the pandemic. Since the pandemic, business has boomed.”

Lami has also worked to elevate the status of women business owners, having served on two boards for organizations focused on gender equality. Looking back through her career, she recognized instances of discrimination within her circles, and she wants to prevent those moments for others.

She has also picked up a couple of notable awards, having been named one of the 50 Most Influential Women by Houston Woman Magazine in 2014 and a Women’s Business Enterprise Alliance Star in 2011. She was a contributing author to the best-selling “Business Success Secrets: Entrepreneurial Thinking That Works,” published by Leaders Press in 2021.

Lami and her wife also own Trotting Spirit Ranch, a horse boarding ranch in Cypress, Texas. The farm includes 25 miles of riding trails, full service for the animals, and the opportunity for horse enthusiasts to try their hand at horse maintenance before diving headlong into ownership.

“I am grateful to have the support and encouragement of my wife, Denise Hamby. I could not have a successful business without her,” Lami said. “She and I enjoy trailblazing with our three dogs, 17 chickens, and 14 horses in Cypress.”

Through setbacks and victories, Lami looks back on her last few decades and finds meaning in both. The value of her combined experience formed her into the person she has become, from serving fast-food burritos to an influential role with a global energy company.

Above all, she most desires being true to herself.

“Be authentic,” she said. “If you can pair your passion with your authentic self, your days are a whole lot less stressful.”