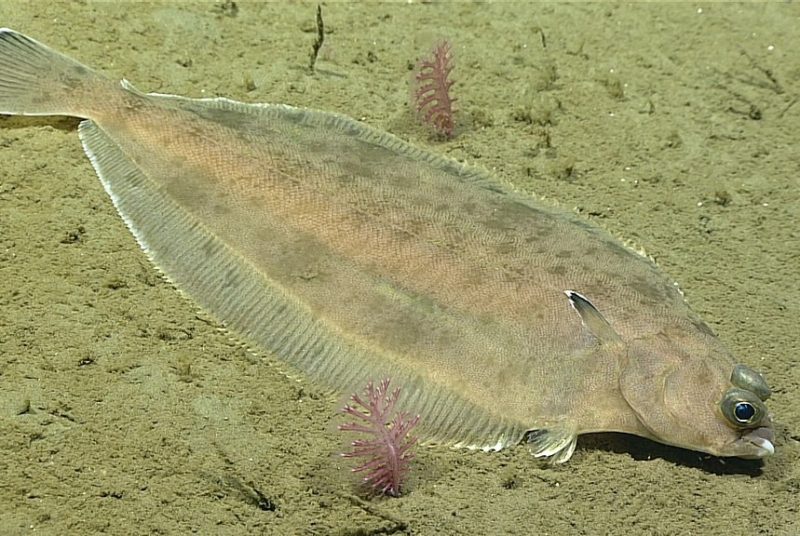

Finding flounder in a changing ocean

Researchers are collaborating with stakeholders to understand how changes in summer flounder distribution and population dynamics are impacting the fishing industry in Virginia.

This summer, a $300,000 federal grant from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Virginia Sea Grant is funding research to explore the population dynamics and distribution of summer flounder, a marine flatfish valued by both those who fish for recreation and Virginia’s fishing industry.

“This project started with a conversation,” said Assistant Professor Holly Kindsvater of the College of Natural Resources and Environment. “While I was visiting the Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center, I found out that a fourth-generation seafood company was right next door. I asked [L.D. Amory Co. Inc. President] Meade Amory what was on the top of his mind, and he said summer flounder.”

That conversation led to a collaborative project between Virginia Tech, government agencies, and fisheries stakeholders that aims to better understand how summer flounder are adapting to a changing environment and how those adaptations could impact an industry that supplies flounder to restaurants and consumers.

“There’s been trouble brewing in flounder waters for years. The summer flounder stock used to be mostly off Virginia and North Carolina, and those two states were given the biggest share of the commercial fishing quotas that were established in the 1990s,” said Kindsvater, who teaches in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation.

“But because of warming waters, summer flounder have shifted their ranges northward toward Long Island, where the quota share of northern states like New York and New Jersey are much smaller. This mismatch between biology and policy have changed the economics of the commercial fishery.”

A second challenge is that the quotas are determined by stock assessments that rely on “recruitment” — the number of summer flounder that make it from their early life in tidal estuaries to life in the open ocean — to determine how many flounder can be caught in a year. Unfortunately, flounder reproduction is a complicated affair.

“Summer flounder have a very flexible reproductive strategy, where they can lay eggs over the course of many months or lay eggs in batches or skip laying eggs entirely,” said Hailey Conrad, a graduate student in fish and wildlife conservation who has been studying flounder in Kindsvater’s lab.

“Species like salmon reproduce in a more predictable way, so it’s easier to get an accurate recruitment assessment. An understanding of flounder reproduction is a huge black box in our knowledge because spawning is indeterminant.”

Collaborating with partners in the fisheries industry has been a boon for Conrad, who was able to sample fish landed at L. D. Amory Co. Inc. and also go on a trawl survey conducted by NOAA. She collected samples from hundreds of summer flounder, gathering key data on size, sex ratio, age, and population health of the species.

“Working with an industry partner like Amory seafood has been a really fortunate arrangement,” said Conrad, who also received funding from the National Science Foundation’s prestigious Graduate Research Fellowship Program. “The spawning season for summer flounder aligns well with the commercial fishing season, so we’re able to get a strong sample to work with.”

That collaboration has revealed that the exchange of knowledge is often a two-way street.

“The captains are often much more in touch with what’s happening with the fish, and their perspective can lend a better understanding than I can get from reading papers,” said Conrad, who is from Seaside Heights, New Jersey. “One time, we were looking to hire a charter boat to collect samples. The captain told us, ‘I can take your money, but you won’t catch anything because summer flounder don’t eat after their annual migration.’ I had never heard anyone say that before.”

For Kindsvater, the chance to collaborate with industry is a critical step in Virginia Tech’s effort to increase sustainability of our fishing resources.

“Trying to determine quotas for fish is an age-old conflict between fishermen and management agencies,” said Kindsvater, an affiliate faculty member of the Global Change Center and the Center for Coastal Studies. “This project was an opportunity to contribute something toward a challenge that stakeholders in the industry and in conservation are seeking clarity on.”

In addition to NOAA and L.D. Amory Co. Inc., contributing partners for this research project include the Virginia Seafood Council, the Virginia Marine Products Board, and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission.