Where clinical psychology and neuroscience converge, this Virginia Tech scientist takes the lead

Neuroscientist Pearl Chiu leads a cutting-edge research laboratory at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute set on finding new treatments for anxiety, substance use, and mood disorders.

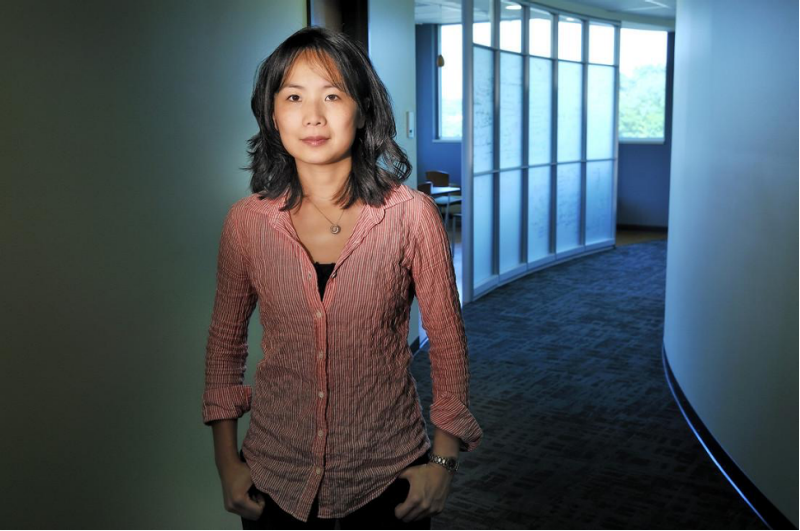

Research by neuroscientist Pearl Chiu, who was recently promoted to full professor, has uncovered unique neural characteristics of major depressive disorder, risky decision-making in teenagers, substance misuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and more. Photo by David Hungate for Virginia Tech.

How are humans motivated to do what we do? That’s the fundamental question driving neuroscientist Pearl Chiu.

“On a neurobiological level, each of our brains is similarly composed. We share the same general structures and cell types — yet as people, we’re all so different,” said Chiu, who the Virginia Tech Board of Visitors recently promoted to full professor with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and the College of Science’s Department of Psychology. “I’ve always wanted to understand the brain’s role in what motivates each of us as individuals.”

As a Harvard-trained clinical psychologist, Chiu once treated patients with psychiatric disorders. Her computational psychiatry research program to understand motivation in mental illness and develop neuroscience-guided behaviorally oriented mental health treatments is supported by more than $2.8 million in annual National Institutes of Health funding.

Chiu’s laboratory combines computational modeling, human neuroimaging, clinical assessments, and behavioral task data to decode how certain reward learning pathways in the brain underlie decision-making in a range of psychopathologies. Her recent research has specifically uncovered unique neural characteristics of major depressive disorder, risky decision-making in teenagers, substance misuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In 2021, she published a hallmark study in the Journal of the American Medical Association outlining how specific reward learning processes are related to symptoms in people with clinical depression. Using cognitive behavioral therapy as a treatment intervention, Chiu and her colleagues, including fellow neuroscientist and professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, Brooks Casas, mapped how reinforcement learning is altered in depression and changes with symptom improvement.

One of her latest projects, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, builds on that work.

“We’re now taking it full circle. We previously mapped out specific cognitive and brain reward learning processes underlying symptoms of depression. The next step is to change those processes and examine whether symptoms improve when we use behavior to stimulate corrective neural adaptations,” Chiu said.

She also is working on a breakthrough project with her colleague Read Montague, professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and director of the institute’s Center for Human Neuroscience Research.

For years, neuroscientists have analyzed neurotransmitter signaling in animal models, but Chiu and Montague are among the first to measure neurochemical signaling in people with depression.

“Based on previous depression research, we can infer that dopamine and serotonin signaling is altered in reward learning regions of the brain, but we’ve never been able to directly measure it in humans until now,” Chiu said.

Study participants include medication-resistant epileptic patients with symptoms of depression who undergo continuous monitoring via electrodes implanted in the brain. Through a small wire — finer than a strand of hair — the researchers can measure sub-second fluctuations in neurochemicals from the same wire that is being used to monitor the electrical activity of the patient’s brain underlying seizures. The researchers will use the data to examine how certain neural pathways are activated during value-based learning tasks.

“By combining direct brain chemistry, behavioral methods, and clinical psychological assessments we’ll be able to make some breakthroughs in understanding and treating depression,” Chiu said.

Chiu has worked for the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute since its inception in 2011. She was among the first group of scientists to be recruited by the institute’s founding executive director, Michael Friedlander.

“Dr. Chiu’s exceptional research program is at the forefront of progressive mental health research,” said Friedlander, who is also Virginia Tech’s vice president for health sciences and technology. “She is among a small group of pioneers who have begun to precisely tease apart the relationship of brain and behavior with a quantitative and rigorous set of scientific tools. Mental health research and the practice of mental health diagnosis and treatment for patients stand to benefit tremendously from this revolutionary new bridge between science and medicine. Aside from her impressive scientific contributions to the field, she is also a highly regarded mentor to our students and a valuable collaborator for her colleagues.”

Chiu previously worked as an assistant professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, after working as a postdoctoral researcher in Montague’s laboratory. Raised partially in Taiwan, Michigan, California, and Boston, Chiu completed her undergraduate degree in psychology and doctoral degree in clinical psychology at Harvard.

We sat down with Chiu to ask her about her career path from clinical psychology to neuroscience and the research projects she’s most excited about.

It’s uncommon for neuroscientists studying mental health to also have patient experience. How has your background influenced your research?

When I was working with patients in the clinics, there was a focus on diagnosis and assessing behavior and cognition – which all have immense value, but don’t give us the full picture. Now my lab is trying to take that a step further by connecting specific symptoms with behavioral and brain reward learning processes so we can identify how individuals are motivated (or not) and work toward developing neuroscience-guided behavioral treatments.

When did you know that you wanted to study psychology and the brain?

I’ve always been interested in how internal and external variables affect how we make decisions. What motivates different people? How does motivation occur? And how are these processes altered in people with mental health disorders? Starting as an undergrad doing my senior thesis research, I’ve been fortunate to have great scientific mentors who came at these questions from different perspectives and who also encouraged me to make my own way. After my postdoc in Read Montague’s lab, I was in the first cohort of neuroscience faculty recruited to the computational psychiatry unit at Baylor College of Medicine and have been on this path since.

Fast-forward 20 years. What excites you most about where your field is headed?

It’s exciting how the field is advancing, and by combining direct brain chemistry analysis, behavioral methods, neuroimaging and clinical psychology assessments, I believe that we’ll be able to make some breakthroughs in understanding and treating depression. These new integrative methods can be more precise than medications or psychotherapy at targeting specific neurocognitive processes associated with disrupted motivation in mental health disorders, and that’s what I’m most excited about working toward.

What advice would you give to an aspiring scientist?

Stay curious. Stay skeptical. Develop good instincts and follow them. And lift each other up. It’s hard enough to succeed without adding unnecessary negativity. I also tell students that the best way to learn is to do. Go beyond the textbooks. Work with real data, make mistakes, and find your mistakes so you learn from them. Making progress in sience is about trial and error and constantly learning new skills.

How has your research and knowledge of neurodevelopment and the teenage brain influenced you as a parent of two?

I collaborate on some of this work with my husband, Brooks Casas, also a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, and it’s been fun to bring our work home to how we parent. A lot of our teenage research is focused on brain mechanisms of risk-taking, and in general, when we talk about risky behaviors, there’s a negative impression. But we have to take risks and explore to get feedback and learn. Research shows that there are many benefits to risk-taking during development. And as parents that’s been a fun challenge — allowing andencouraging risk-taking so our kids can experience a full range of consequences and develop their own instincts.

The Chiu laboratory is recruiting volunteer research participants for four neuroscience projects at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.