Fralin Biomedical Research Institute scientists tie improved learning processes to reduced symptoms of depression

Brain imaging, mathematical modeling reveal previously unreported mechanistic features of symptoms associated with major depressive disorder

Illustration to tell the story of how brain mechanisms can be explained in numbers.

Virginia Tech scientists with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC have identified neural learning processes to be associated with symptoms of depression and linked improvements in these processes to improved symptoms in research participants being treated for depression.

The findings, described in a study published July 28 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Psychiatry, suggest distinct paths to depression symptoms and new mathematically guided approaches for treating clinical depression.

Major depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and can cause severe impairment, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. An estimated 7.1 percent of all U.S. adults have had at least one major depressive episode.

“Current medications and behavioral therapies are helpful, but for many people struggling with depression, existing treatments don’t work well,” said Pearl Chiu, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute Computational Psychiatry Unit and the study’s corresponding author. “We need to consider other possible paths to depression. These paths, or mechanisms, could point to new treatment targets to explore.”

The scientists used computational models of brain functioning as a new way to consider mechanisms of depression. In a key discovery, the researchers found that the symptom improvements that followed cognitive behavioral therapy were related to improvements in reinforcement learning components that were disrupted prior to therapy.

“Depression is a very serious illness and a leading cause of disability in the world. We hope that our work can be a bridge between behavioral clinicians and computational scientists to more precisely identify what causes depression and new ways to treat the illness,” said first author Vanessa Brown, a former doctoral student with Chiu in Virginia Tech’s Department of Psychology who is now an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

The research team began studying a baseline group of 101 adults with and without clinical depression. A subset of the participants with depression were treated with up to 12 weeks of cognitive behavioral therapy — a treatment that involves learning how to identify and correct negative thought patterns.

Participants with depression played a learning game during functional MRI brain scanning before and after cognitive behavioral therapy, and participants without depression played the same game at time points matched to participants who took part in cognitive behavioral therapy. The scientists used computational modeling to identify different processes that contribute to learning. They found that distinct components of learning about rewards and losses — known as reinforcement learning — were connected to certain symptoms of depression.

“Two of the most exciting parts of the findings are that people with depression learn in different ways and that these learning processes changed when depression symptoms improved after cognitive behavioral therapy. The link between the learning components and symptoms is critical,” said Brooks King-Casas, co-author of the study and an associate professor with the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and in the Department of Psychology in Virginia Tech’s College of Science.

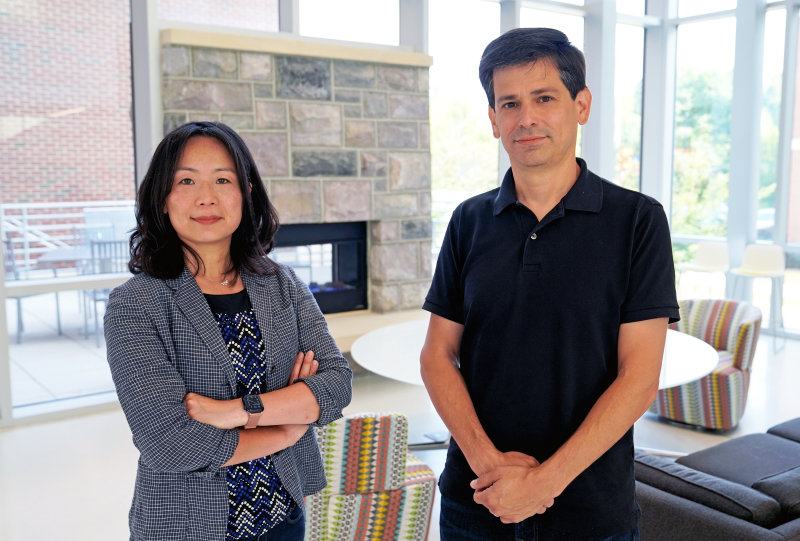

In a key discovery, Virginia Tech scientists Pearl Chiu and Brooks King-Casas of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC found that the symptom improvements in patients with depression who had received cognitive behavioral therapy were related to improvements in reinforcement learning components that were disrupted prior to therapy. (Whitney Slightham for Virginia Tech)

The researchers say using computational models has potential to help other investigators and mental health professionals precisely identify new contributors to depression, which in turn could be new targets for therapies.

“An example is that for someone with depression, losing a few cents in the game could feel like losing several hundred dollars or the loss could be very hard to forget. These processes are different, but both affect how we learn and the choices we make,” King-Casas said.

“We quantified some of these learning processes with computational modeling and show that they relate to depression in very different ways,” said Chiu, who is also an associate professor of psychology in Virginia Tech’s College of Science. “The idea is similar to how stress or too much sodium can both contribute to high blood pressure, but what contributes to a particular person’s hypertension could suggest whether they focus on decreasing stress or reducing salt consumption as part of treatment. Similarly, for depression, the parts of learning that contribute to a person’s depression could call for different approaches to treatment.”

Chiu said forming a computational understanding of how cognitive processes align with symptoms of depression is a promising approach.

“Now that we’ve linked specific components of learning to depression and show that they change with specific depression symptoms, perhaps we can develop new therapies that focus on adjusting these learning components as a way to reduce depression,” she said.

Additional former students and postdoctoral associates who contributed to the public impact research study include Lusha Zhu, Alec Solway, John Wang, and Katherine McCurry.

The study was funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, part of the National Institutes of Health.