Research collaboration uncovers stories of racial discrimination in housing covenants

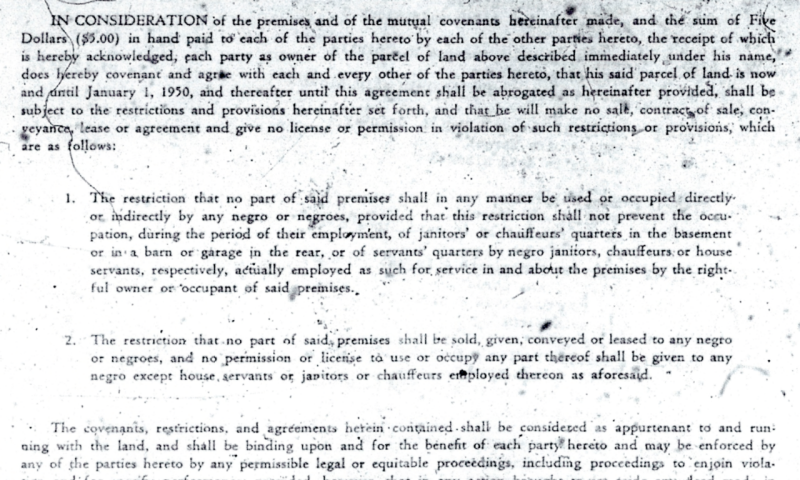

Buried in the files of Chicago's Cook County are records of racially prohibitive covenants and deed restrictions. In the first half of the 20th century, these legal instruments promoted racial segregation. First created and deployed by individuals, real estate leaders, and economists who led national organizations based in Chicago later embraced them. During this time, covenants and restrictions covered about 80 percent of homes.

A research collaboration between University Libraries and the Department of History in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences at Virginia Tech, along with students at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University, is unearthing the stories of how racial segregation in Northern cities were intentional. Evidence proves that “it was a system that was intentionally created, house by house, block by block, and subdivision by subdivision, across the city and across the country,” said LaDale Winling, associate professor of history and the study's principal investigator.

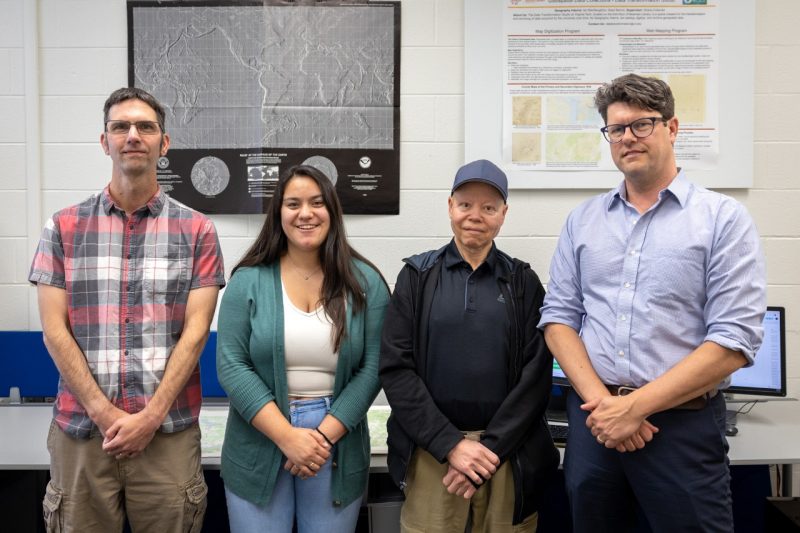

A multidisciplinary team at Virginia Tech is digging into these historic records and shining a light on this important racial issue:

- LaDale Winling, associate professor of history, principal investigator

- Jonathan Petters, assistant director of data management and curation services and principal investigator for library research

- Kara Long, metadata technologies coordinator and principal investigator for library research

- Ed Brooks, geospatial data consultant

- Katherine Humphreys, library student employee who earned bachelor's degrees in meteorology and geography this spring

Originating as an awarded Libraries Collaborative grant and most recently a $150,000 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, this project focuses on metro Chicago and explores two questions: How widespread were the covenants? What role did these racial covenants play in creating and maintaining racial and spatial inequality in metro Chicago?

To answer these questions, the team is creating best practices and data and metadata standards for capturing, managing, and archiving covenant documents. Data tools such as ArcGIS and Tableau will facilitate the analysis and visualization of these covenants after digitization.

Racial covenants and deed restrictions were used in a scattered, uncoordinated fashion until the 1910s, when a leading real estate developer began heavily using and promoting deed restrictions. Ten years later, a Supreme Court decision let a racial covenant in Washington, D.C., stand. Afterward, their use spread far and wide.

Commonly, covenant documents contained explicit racial restrictions that only allowed white people to own or inhabit properties. These restrictions would remain in effect even when the properties changed hands, and some restrictions included whole subdivisions.

The team found the sheer number of these covenants that exist in the area far exceeds initial estimates. Although this project’s focus is the Chicago area, racial covenants are present in many cities around the United States.

“The existence of covenants was well-known, but these documents were often scattered in the collections of county land records archives along with mortgages, sales, and other property transfers,” said Winling. “Finding a racial covenant was like finding a needle in a haystack. Many research efforts since the 1940s gave up or sampled the neighborhoods because the research was too labor intensive.”

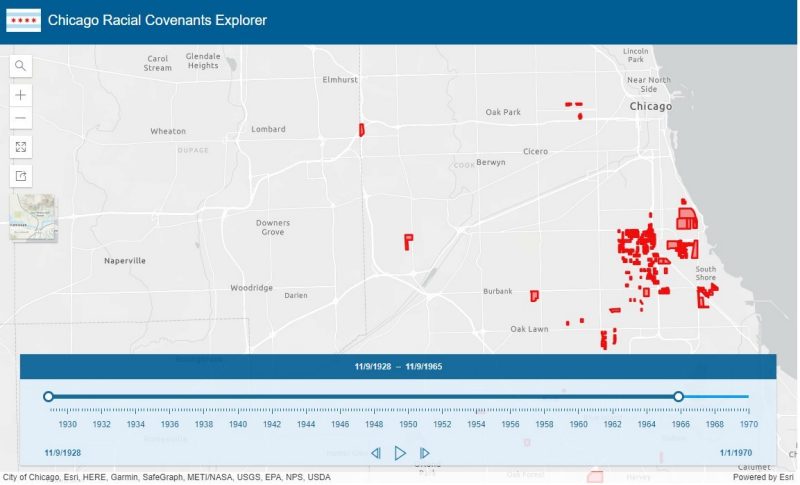

The team aims to eventually identify and interpret every covenant in Cook County, showing how widespread the covenants are and were. In addition to creating a metadata standard to document these files, University Libraries has created an interactive webmap to aid in the visualization of racial covenant locations in Chicago — and, one day, beyond.

“The webmap shows that in many Chicago neighborhoods, there were no properties that were untouched by racial covenants,” said Winling. “It helps lead the way for research projects in cities all over the country.”

“My passion for this project centered around the use of mapping/GIS as a powerful tool for exploring social justice issues, like racial inequality in its past and present forms,” said Brooks.

Humphreys, the lead creator of the webmap, designed it to show the location of and information about racial covenants in several of the main neighborhoods in Chicago and in Cook County, but it wasn’t easy.

“While making the webmap, one of the biggest challenges for me was deciding how to design the map,” said Humphreys. “Design is really important because how you visualize and present a map will influence how users perceive and understand racial covenants in general. We put a lot of thought into the layout and design so that we could give users the most information in a clear, concise, and intuitive way.”

“I was surprised that there are not many projects like this, so there was not a standard blueprint to follow,” said Humphreys. “This gave us a lot of flexibility which was amazing, but when making decisions we had to be very thoughtful and create our own standards as we went.”

Humphreys said she is passionate about this project because it sheds light on how racial inequities today can stem from the exclusion of black communities in the past. “It’s crazy to me that webmaps can visualize, share, and convey new information in ways documents cannot on their own. Simply showing where racial covenants existed in Chicago can present opportunities for learning and conversations about racial inequality.”

The power of webmaps

“This project serves as a great example of how geospatial visualizations like webmaps can be used to convey a lot of information about a topic quickly,” said Petters. “Chicago-area citizens in particular neighborhoods can easily see whether their residences or nearby residences once had restrictive covenants upon them, and this can spark their curiosity, interest in, and engagement with the topic. As more covenants are added to the map, we expect engagement will increase.”

Winling said researching racial covenants is one of the ways that scholars can recognize and explore the work of the legal Civil Rights Movement at mid-century. “Collaborating with the library is particularly rewarding because it helps introduce new modes of research and communication. When historians find and collect paper documents and write about them, they normally only need to be comprehensible to one person - the historian. But we are creating a digital archive for the public, meaning hundreds of thousands of viewers could be navigating the resources. To manage files and outreach like that, you need a librarian to discuss your document organization, how to scale up your data management, public communication needs, and how to think about your end users and prioritizing their different needs.”

University Libraries’ geospatial data services are highly collaborative with students and faculty across the university and beyond with projects like this one. “As a student, I loved working with the library because it gave me the opportunity to take the skills I learned in class and apply them to a topic that I never thought I would work in,” said Humphreys. “This experience with the library gave me work experience for the future and helped me explore what I like and want out of a future career.”