Veterinary college alum Bruce Bowman carries serving others to new heights around the world

Bruce Bowman has made a life and a living serving veterinary clients in his native Shenandoah Valley as well as residents across Virginia, but his committment to Virginia Tech's motto, Ut Prosim (That I May Serve) has also flowed across the oceans to the highest mountain passes on Earth.

Bowman, who earned a degree in animal science in 1983 and a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in 1987, led a successful private veterinary clinic for large and small animals in Waynesboro, Virginia, for more than 25 years before working as a field veterinarian for the commonwealth for another decade.

He has been on five international veterinary trips: two to Kashmir, two to Mongolia, and another aboard a ship hauling livestock to Egypt. He hopes to return to Mongolia soon and also visit Vietnam for the first time.

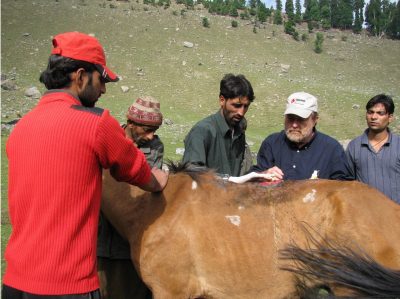

At the Virginia Veterinary Medical Association’s February meeting, Bowman captivated an audience of fellow veterinarians with a recounting of his international adventures, particularly those assisting the Gujjar herders of Kashmir in their seasonal drive of sheep and goats through glacier-studded Himalayan passes back to summer grazing pastures.

“I really have a passion for groups who rely solely on livestock and poultry for their means of making a living,” said Bowman. “So there is a fair amount of service that I can bring that can help them. I'm a trainer. I think all veterinarians are trainers, and teachers. ... And part of the reason that I've continued to go is because I love the teaching aspect. And you'd be so terribly surprised at what tiny little basic steps that you can describe to someone in a nomadic culture, tiny little basic steps that make a difference.”

His trips have taken place through Christian Veterinary Mission (CVM), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

He has often been struck by situations that are routine here but have entirely different context in nomadic cultures abroad.

“So we're playing with balloons one afternoon, and one of them tumbled to the ground, hit a sharp stick, and popped,” Bowman recalled. “The children ran away screaming because they thought it was an explosive. And it took half an hour, truly a half an hour of coaxing, and educating and teaching these young children to come back, that it's a toy, that it's something you can play with. But that's the world they live in. They're living on the battleground of where India and Pakistan are fighting over territory.”

Another time, Bowman saw a piece of the duct tape he had used to bind medicine-soaked cotton balls to injured sheep’s feet on the forehead of a child.

“I noticed that little girl with that one-inch square piece of duct tape on her forehead,” Bowman said. “I had a pretty hearty laugh about that. And my host said, ‘You don't understand, doctor, what her parents saw was that when duct tape was applied, the feet got better.’ And so they attributed the healing of those feet to the duct tape. … That was a moment for me to reflect on.”

There have been many such moments for Bowman. Particularly poignant was an audience with the Muslim shaman of the Gujjar.

“You Westerners, you worry about what you don’t have instead of being thankful for what you do have,” Bowman recalled the shaman saying while waving his hands toward the majestic Himalayas scenes he had lived in his entire life.

Bowman, who described the purpose of his work among the Gujjar with Christian Veterinary Mission as “being the hands and feet of Jesus,” said he felt convicted by the shaman’s statement.

“There’s no religion that prevents you from understanding that there is great wisdom in everyone that you meet,” Bowman said. “It's just a matter of whether or not you can cultivate those pearls.”

Admiring a majestic Himalayas scene with a Muslim shaman miles above sea level is a long way from where Bowman would have expected to be in his younger life.

“Growing up, I didn't have any interest in international travel,” Bowman. “In fact, I was happy to stay in Virginia, I think I saw the ocean once before I graduated from high school.”

Four years in the U.S. Coast Guard, hiking the Appalachian Trail, and making two cross-country motorcycle rides before his Virginia Tech college years changed some of those perspectives.

More recently, stepping into international missions applying his veterinary skills and experience have expanded those horizons even farther.

“Someone else pushed into my life that this is something I needed to do,” Bowman said, referring to a younger female colleague in his veterinary practice who shared his faith. “And I drank the Kool-Aid, and I've been hooked ever since. So it was at someone else's suggestion. It was not self-initiated.”

Bowman’s work has introduced modern science into cultures deeply steeped with generations of wisdom in raising livestock, and his efforts are generally well received. But he doesn’t want livestock farmers in the U.S. or abroad thinking “herd management comes out at the end of a needle.”

“Herd management requires more than just antibiotics and nutritional supplements,” Bowman said, “because shots never will be a substitute for good management and good nutrition.”

Bowman is quick to puncture Western assumptions and presumptions of other cultures.

For instance, he pointed out that Mongolians don’t really call their huts “yurts” because that is a Russian word and Mongolians have deep historical enmity with Russia. Rather, they call it a word that sounds like the English “gear.”

Reminiscent of the “App-uh-lay-shun” vs. “App-uh-latch-un” debate over the pronunciation of our Appalachian mountains, Bowman said the locals refer to the Himalayas as the “Him-uh-lah-yuhs” not the “Him-uh-lay-uhs” as most Americans pronounce it.

But Bowman said his international trips have also made him appreciate the United States even more.

“One of the things that makes me appreciate what we have in the U.S. and the reason that I'm particularly patriotic is to see what other countries are like and what their freedoms are like,” Bowman said. “I think that, particularly for livestock veterinarians, if they visit other countries and work with livestock, they will quickly see that we have a lot to work with compared to what our international community experiences.”