First in the family

On their paths to graduation, many first-generation students must contend with a variety of structural and social barriers. A slate of Virginia Tech programs supports them as they strive for success. Part 1 of a two-part series.

Christine Strouth, a rising senior studying psychology, has come a long way since the beginning of her college career.

“Going into college, it was hard to talk to people at first, and I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing,” the native of Virginia’s Dickenson County said. “My biggest hesitancy with coming to Virginia Tech was that I was going to be jumping into the dark. I was really nervous about not being able to succeed.”

Nearly all college students must endure some social and emotional discomfort as they adjust to university life, but for Strouth and thousands of other Hokies like her, their college experiences are profoundly shaped by one crucial distinction: upon graduation, they will be the first people in their families to have earned college degrees.

Though each student takes a unique path shaped by individual strengths and personal experiences, students like Strouth, known to Virginia Tech and universities across the country as “first-generation,” — meaning neither of their parents or guardians has a degree from a four-year college or university — tend to face a number of particular challenges as they strive for success in college and beyond.

Christine Strouth '22 attends an event for first-generation Virginia Tech students in 2019.

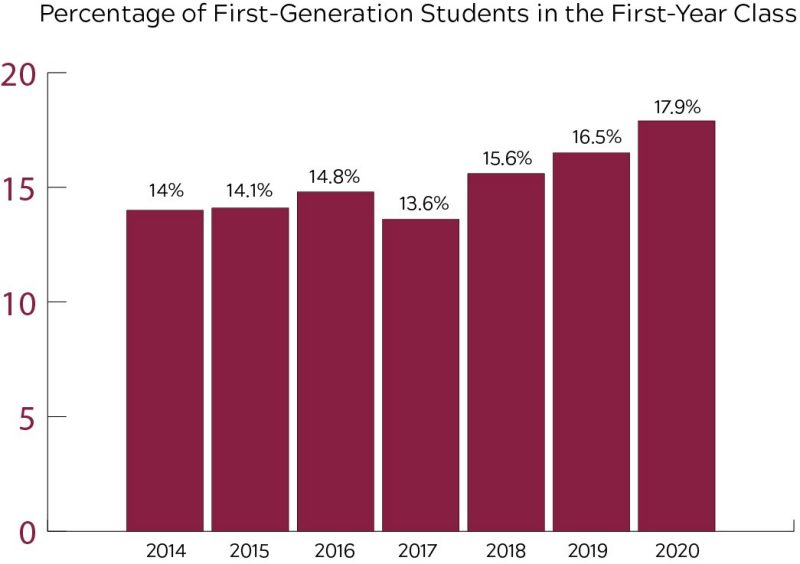

About 17 percent of Hokie undergrads were first-generation students in the fall of 2020, up from 15 percent in 2018. Overall, there were more than 5,000 first-generation undergrads enrolled at the university this past fall, including more than 1,000 first-year students, according to statistics from the Virginia Tech Office of Analytics and Institutional Effectiveness.

As part of the university’s efforts to serve and support underrepresented and underserved students, among whom first-generation students are included, a host of programs — some new and some long-standing — aim to help first-generation Hokies succeed in their social, academic, and professional goals.

These programs include substantial efforts by Student Affairs and the Dean of Students Office, and have received considerable investment from passionate alumni and supporters who care deeply about improving the first-generation experience at Virginia Tech.

Paula Robichaud ’77, who was a first-generation college student herself, provided a substantial boost to first-generation programs with a generous gift in 2019. Her support made it possible for the university to launch a first-generation student initiative and conduct a national search for a director to oversee first-generation programming.

“I want to pay it forward by supporting Virginia Tech students who, in turn, will make opportunities possible for those who follow them,” Robichaud has said. “Everybody should have a chance at a good education, to see what they can do with it. Isn’t that the American dream? We are all in this together. It’s as simple as that.”

At nearly 18 percent of the first-year class in 2020, the amount of first-generation Hokies beginning their Virginia Tech journeys has grown in recent years. Data provided by the Office of Analytics and Institutional Effectiveness.

Charmaine Troy served as the university’s first program director for first-generation student support from August 2019 through March 2021 and now leads first-generation student programming at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“Students who are the first in their families to attend college bring unique perspectives and experiences to the classroom and campus,” Troy said in November 2020, shortly after Virginia Tech was named one of the Center for First-generation Student Success’ First-gen Forward institutions for 2020-2021. “Every student needs general advice about how to excel in college, but first-generation students aren’t usually able to get that advice from their family, where many other students get it, because their family doesn’t have that first-hand experience.”

For many, that lack of familial experience with the world of higher education can place them at a relative disadvantage compared to their peers from degree-holding families, even before arriving on a college campus.

What to Expect

Strouth’s parents encouraged her to apply for college despite financial limitations and a lack of first-hand knowledge of the process. She applied to five universities and was accepted to all of them, but was left with even more questions.

“After I got accepted, I was like, ‘How do I decide which one to go to?’,” she recalled asking herself. “Do I have to commit to one before they give me financial aid?”

Strouth credits a special program she participated in while in high school with making her more ready for college.

“Each summer, I would go to the campus of a college near our home for a pre-college program called Upward Bound,” she said. “We got to know the campus, took some classes, and learned about applying to college. They could answer questions about financial aid and applying for fee waivers.”

“I always knew that, if I completed college, I would be the first person in my family to do so,” Strouth continued, “but Upward Bound introduced me to the term ‘first-generation student.’ It helped me understand what to expect when I got here.”

Upward Bound is part of TRIO, a group of student services and outreach programs administered and funded by the U.S. Department of Education. It aims to help high school students overcome social, academic, and cultural barriers to higher education.

Throughout the country, hundreds of college campuses now host TRIO programs like Upward Bound on their campuses each summer with funding awarded by the federal government. Virginia Tech has worked with the programs since their very beginning more than 50 years ago.

“The Upward Bound and Talent Search programs in Southwest Virginia are two of the oldest such programs in the nation, going back to the beginning of TRIO in the 1960s,” said Frances Clark, the university’s director of TRIO programs. “Maintaining funding and continuity that long is fairly unique.”

Virginia Tech’s three Upward Bound programs — which include a regional program for Southwest Virginia as well as programs for Salem and Roanoke City — collectively serve more than 200 high school students each year. All participants come from families who fall within specific income guidelines, and two-thirds of those served must meet the criteria to be considered first-generation students when they eventually enroll in a college or university.

Traditionally, a major component of the Upward Bound experience at Virginia Tech has been a six-week, on-campus, summer intensive program aimed at getting students ready for college. Participants ranging in age from rising ninth-graders to rising first-year college students live in dorms, eat in the dining commons, tour multiple college campuses in the region, receive crucial support in navigating the process of applying to schools and for financial aid and scholarships, and take cross-curricular and project-based classes focused on core subjects needed for academic success in higher education, among a variety of other activities.

Students who participate in Upward Bound at Virginia Tech are under no obligation to apply to the university, though Clark shared that many ultimately choose to because of the familiarity and affection they develop for it. According to Clark, 83 percent of Upward Bound participants go on to enroll in post-secondary education, compared with 51 percent of students who do not participate but meet the eligibility criteria.

In addition to the summer residential program, all students participating in TRIO programs at Virginia Tech are eligible for tutoring and academic advising.

“We want our students to see college as a viable option and to feel that they have the tools they need to succeed there,” said Jason Puryear, the university’s associate director of Upward Bound programs. “Because many of our tutors are first-generation students themselves, they can talk to students in Upward Bound about their own experiences and help fill in the gaps of what it's like to be a college student.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided the TRIO team at Virginia Tech with the opportunity to reimagine how to meet the needs of its students, and this summer will mark the second year in a row that the summer intensive program has been run remotely.

“Going forward, I believe our reach will be much broader because, during the pandemic, we’ve learned ways we can change our approach,” Puryear said. “We will continue to focus on face-to-face, in-person programming when it is safe to do so, but we’ll also be able to cast a wider net using a greater variety of tools. The pandemic has challenged our staff to better reach our students where they are, and I think our post-COVID reality will benefit from some of the lessons we have learned.”

Though the manner in which they provide their services has evolved and will continue to do so as the needs of students change, Clark and Puryear are confident that their programs will continue equipping students like Strouth with the skills and knowledge they need to begin their journeys toward earning their degrees.

Strouth, who has gone on to serve as a mentor to other first-generation Hokies, urges them to remember that they’re not alone at Virginia Tech. “It’s okay to be aware of feeling out of place,” she said. “But remember, just because your parents didn’t go to college doesn’t mean you’re not supposed to.”

Getting In

First-generation students often report that their parents strongly supported their children earning a college degree but were able to provide relatively little guidance on the application process because of a lack of first-hand experience.

“My parents really encouraged me to go to college,” said Ciara Summersgill ’21, who graduated in May with a double major in water resources policy and management and geography. “They never got to go, and so they were motivated to make sure I got the opportunity they didn’t have.”

“Applying to college was a real process,” she recalled. “It was scary, and I basically did it on my own. I had to figure out things like how many schools I should apply to. I remember being really nervous the first time I went on a campus tour because I had no idea what to expect.”

Her first year at Virginia Tech, Summersgill reflected, was much more challenging academically than she had anticipated. “The entry-level classes that you have to take in order to move on in my major were awful. I called dad crying about general chemistry, I struggled with that class so much that I almost changed majors. But I stuck with it to get on to classes later that I knew I would enjoy.”

Summersgill added that she “definitely knew I was on the right path because I have always had a work-hard mentality, and I knew my work ethic meant I would keep trying. But I had to learn that getting an A or a B was not the only way to be successful.”

Ciara Summersgill, a first-generation alumna and Beyond Boundaries scholar who completed her degree this past May.

Meeting her own high academic standards wasn’t the only significant hurdle Summersgill had to overcome on her path to graduation.

“I feel like the challenges for first-generation students have a lot to do with family finances and the ability to pay for college,” she said. “I always sort of knew that I would go to college, but what that would look like and where I would go would be up to scholarships and financial aid.”

Paying for college is a big and challenging piece of the puzzle for many first-generation students and their families. Though each family’s financial situation is unique and influenced by a variety of factors, workers without college degrees tend to earn less overall than their degree-holding peers. According to a May 2020 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. workers aged 25 and older whose highest educational certification is a high school diploma earn an average of 40 percent less than those with bachelor’s degrees and face an unemployment rate of 3.7 percent compared to 2.2 percent for college graduates.

While those statistics help make it clear why so many parents of first-generation students express a strong desire that their children earn college degrees, they also shed some light on the economic obstacles families without degree-holding income earners face in trying to succeed in higher education.

“The financial piece is a big barrier,” said Deana Waintraub Stafford, associate director of the Center for First-generation Student Success, a national organization based in Washington, D.C., that conducts research and advocates on behalf of first-generation students. She pointed out that first-generation students often cannot rely on the same level of financial support from their families as students from families with greater economic stability.

A slate of student support programs aim to help alleviate some of the effects of these social conditions faced by Virginia Tech students that might otherwise prevent them from continuing to work toward their degrees. The Office of First-Generation Student Support provides crucial information to students about grants and financial resources available to help them stay on track in pursuit of their goals.

Some Virginia Tech programs are designed to offer immediate support to all types students in the moment when they need it most. The Student Emergency Fund, for example, gives direct cash assistance to students in urgent need of assistance paying for essentials like rent, groceries, or utilities. The fund provided over $187,000 in assistance to more than 260 students in the 2019-20 school year alone.

Another program, the Market of Virginia Tech was launched in the fall of 2020 with a generous contribution from alumni Hema and Mehul Sanghani and provides hundreds of meals a week during the spring and fall semesters to students struggling with food insecurity.

Additional programs advance the university’s vision of a campus where all Hokies have the resources and support they need to succeed. Beyond Boundaries, Virginia Tech’s strategic plan, lays out the ambitious goal of having an entering class (first-year and transfer students) consisting of 40 percent underrepresented and underserved students, which includes first-generation ones, by 2022.

Key to achieving that goal are scholarship programs which offset the cost of higher education for students and families who may not otherwise be able to afford it.

The InclusiveVT Excellence Scholarship Award, which provides financial support to students from underrepresented minority communities, and the Beyond Boundaries Scholars program, donations to which are matched by the university and which this past academic year provided support to 331 undergraduates, are just two of the hundreds of scholarship and grant programs available to current and prospective students throughout the university.

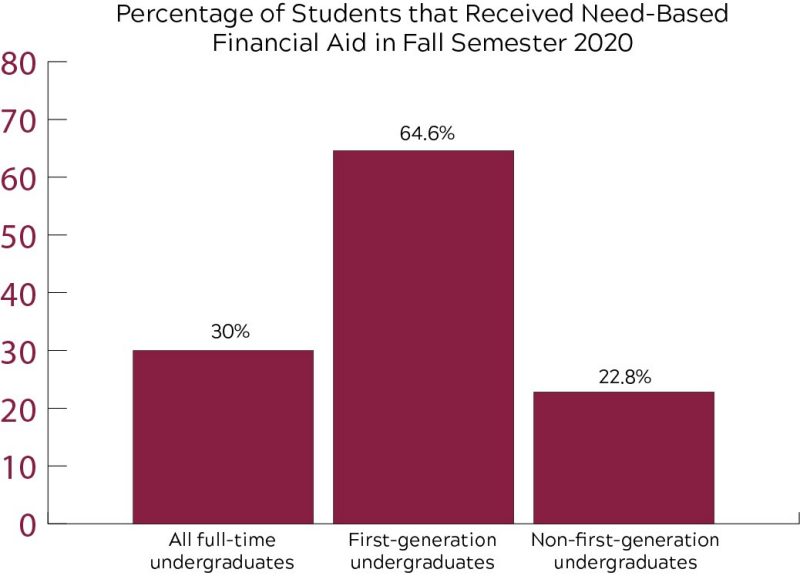

First-generation students benefit significantly from programs like these at Virginia Tech. Nearly 65 percent of first-generation undergraduates at the university receive some form of need-based scholarship or grant aid — compared to 30 percent of the overall full-time undergraduate student body.

These efforts to help current and aspiring Hokies pay for their education make a significant impact on the lives of the students that benefit from them. Summersgill, a Beyond Boundaries scholar, put it succinctly when describing the impact the program has had on her.

“My scholarships make it possible for me to be at Virginia Tech,” she said.

Applying to college, and figuring out how to pay for it, are significant hurdles first-generation students must overcome. They are also just the beginning of their journeys to graduation. Part 2 of this series will explore some of the innovative programs that are helping first-generation students find their footing and pursue their passions at Virginia Tech.

Read Part 2

-

Article Item

Category: culture First in the family , article

Category: culture First in the family , articleOn their paths to graduation, many first-generation students must contend with a variety of structural and social barriers. In this two-part series, we look at a slate of Virginia Tech programs that supports them as they strive for success.