Virginia Tech leads $2.6 million study of brain trauma, epilepsy connection

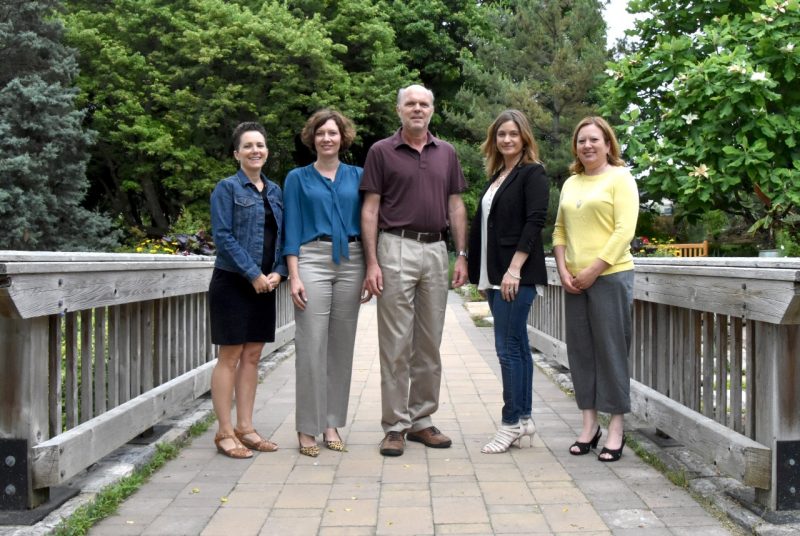

Left to right, Michelle Olsen, Stefanie Robel, Harald Sontheimer, Michelle Theus, and Pamela VandeVord

Virginia Tech is launching a $2.6 million study to determine if traumatic brain injuries can cause changes within the brain that lead to epilepsy.

Funded by the nonprofit Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE) and the U.S. Department of Defense, the three-year study seeks to identify the root causes behind why a person may develop epilepsy after he or she has suffered brain trauma, including sports-related concussion and focal contusion injuries.

Five Virginia Tech groups are heading the study: The School of Neuroscience, part of the College of Science; the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute (VTCRI); the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine; and the College of Engineering. All of the research leaders have wide experience in brain injury and neurological disorders.

“These are the type of injuries you get falling off a skateboard or playing contact sports,” said Harald Sontheimer, executive director of the School of Neuroscience and the I.D. Wilson Chair in the College of Science. Sontheimer is also director of VTCRI’s Center for Glial Biology in Health Disease and Cancer and has a career-long interest in epilepsy.

“The unique aspect of the research is that we are specifically examining which form of injury causes epilepsy and whether there are predictive biomarkers to tell who will or will not develop epilepsy as a result of injury,” Sontheimer said.

Michelle Olsen, an associate professor of neuroscience, will spearhead identification of genes and their subsequent protein products that are common to different injury models. She has expertise in juvenile head trauma, genomics, and proteomics.

Stefanie Robel, an assistant professor at VTCRI, the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and the School of Neuroscience, has studied the effects of concussions and traumatic brain injuries on glial cells within the brain and will lead work at her EEG laboratory in Roanoke.

Michelle Theus, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology in the veterinary college, will study the role of glial-stem cell interactions in post-traumatic epilepsy across various types of head traumas. She has studied the impact of traumatic injury on brain function for more than 10 years.

In the College of Engineering, Pamela VandeVord, the N. Waldo Harrison Professor and interim head of the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics, will study specific aspects of the glial response in the brain. She has studied long-term outcomes of blast-related brain injuries.

An estimated 4 million people suffer head injuries annually, many of them related to professional sports, recreation, or vehicular accidents. A significant number of people who suffer traumatic brain injuries will develop epilepsy, a chronic disorder marked by recurrent, unprovoked seizures.

According to CURE, 65 million people suffer from epilepsy worldwide, with 1 in 26 people developing the illness in their lifetime. Often considered a genetic illness, more than half of all cases of epilepsy are the result of trauma to the head, by far the leading cause of the disorder.

“For over one-third of the affected patients, no effective treatment can be found, leaving them disabled for life, often unable to live independently and participate in the workforce,” CURE said.

The Department of Defense has a keen interest in the research, Sontheimer said. Roughly 80 percent of injured veterans returning from recent wars have suffered a traumatic head injury, and even personnel who return seemingly uninjured often develop depression, anxiety, and epileptic seizures months or years after their return.

The CURE Foundation itself was formed by families who ultimately came together to find a way to halt or minimize medically intractable forms of epilepsy. Since its founding in 1998, CURE has sponsored more than 200 research awards to study a wide range of epilepsies. In 2015, CURE partnered with the Department of Defense to identify researchers that could study trauma related epilepsy. This competition resulted in Virginia Tech being selected to carry out research.

“In the past, concussions were often dismissed as inconsequential, yet numerous prominent athletes have developed profound neurological illnesses ranging from depression to Parkinson’s disease, suggesting that even mild repeated injuries have the potential to dramatically affect brain health,” Robel said.

Added Theus, “Brain injury is the leading cause of acquired epilepsy, with seizures often forming many years after the initial injury. The degree to which repeated mild traumatic brain injuries or concussions can trigger epilepsy in, for example, football players, is unknown.”

During the three-year study, the team will identify the changes that happen in the weeks and months following a brain trauma. “We suspect that we will find genetic and cellular changes that are common to a variety of injuries,” Olsen said.

“The affected genes and proteins may then allow us to create strategies to prevent the brain from developing epilepsy after a blow to the head or blast exposure from battle,” VandeVord said. “The real goal is to take advantage of this period during which the brain appears to change to prevent the disease from happening.”

Joining the faculty researchers on the project will be undergraduate and graduate students and postdoctoral researchers across each of the groups. Among the undergraduates is Lauren Haacke, a junior from Lorton, Virginia, majoring in the School of Neuroscience.

Haacke takes the research in Sontheimer’s lab personally, having suffered a serious head injury during a high school cheerleading accident.

“I was told I’d recover in a couple of weeks, but my symptoms only worsened during the next couple of months. It is largely an ‘invisible’ injury, but it can be so debilitating,” she said. “I still struggle with chronic migraines and nausea, but being part of this program motivates me each day. Working in the Sontheimer lab and contributing to these amazing research projects as an undergraduate is an achievement I would have never thought possible.”

Related stories

Scientists watch the CLOCK gene for potential epilepsy connections

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)