Virtual reality brings dog's anatomy to life for veterinary students

Sara Farthing, a first-year student in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech, needed a mental picture.

As she practiced clinical exams on dogs during a lab, Farthing could not picture the canine’s lungs and the way the heart is positioned inside the chest.

So she walked across the room and slipped on a virtual reality (VR) headset. Suddenly, she could see a large picture of a dog’s lungs and skeletal structure floating in mid-air in front of her.

“I literally stood inside the rib cage,” Farthing said.

The aspiring small animal veterinarian was using a new technology available this semester at the college that brings a dog’s anatomy to life.

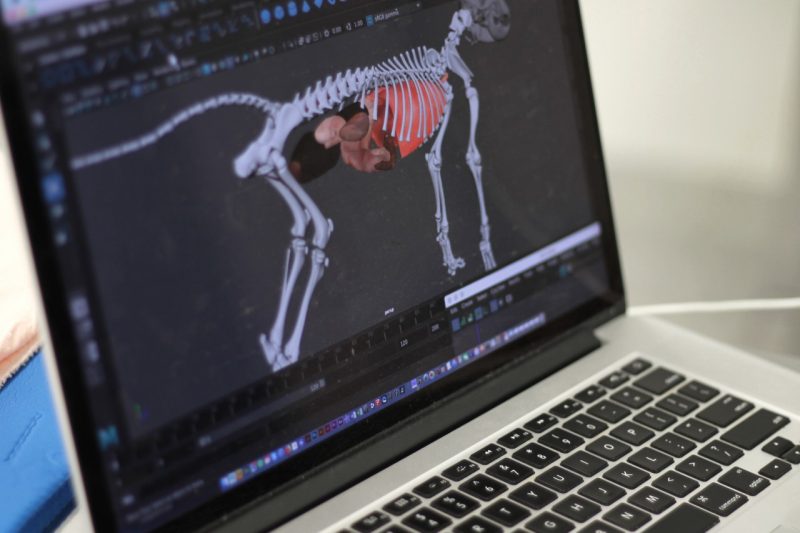

The VR experience, created by Thomas Tucker, an associate professor in Virginia Tech's School of Visual Arts and fellow with the Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology, shows up close the organs inside the skeletal system of a mid-sized dog. By moving and clicking a button, users can see layers of tissue, zoom in on certain organs, and step into parts of a virtual dog’s body.

There is no other way to study a dog’s organs and bone structure as intensively, said Michael Nappier, an assistant professor of community practice in the veterinary college’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences. Nappier teaches clinical skills education and a physical exam lab for first-year students.

When the college switched curriculum models three years ago, Nappier noticed that students were struggling to connect their anatomy classes with what they were learning when they physically examined dogs. The anatomy was taught concurrently with the physical examination, instead of beforehand.

“I needed a different teaching method,” Nappier said. “They [students] don’t have the mental picture. I wanted to develop a way for this to be in the lab and to work with the dogs, so that the mental picture is inside of your head.”

Other ways that students may study a dog’s body parts involve examining drawings and cadavers. But in most of these cases, dogs are not standing on four legs as they would be during a typical veterinary examination. The new VR experience shows an image of a dog standing.

Nappier heard about Tucker’s past work with VR and puppy motion capture, a visualization tool to study a puppy’s social behavior. He contacted Tucker about his idea, and Tucker ran with it.

Since then, Tucker and five graduate and undergraduate students, most all creative technologies majors, have been crafting this 3D VR image of a dog by using CT scans to place the organs correctly. They also worked with Bonnie Smith, an associate professor of anatomy in the college’s Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, to name the bones in a dog’s body and to position them correctly.

Unreal Engine, used by video game developers, is the software that runs this technology.

The project received a $3,000 University Libraries Open Education Faculty Initiative Grant, which requires that the software be publicly released under an open license for use by other universities and veterinarians as part of Virginia Tech’s land-grant mission.

“This open source tool brings forward the ability for students to develop a better spatial understanding,” said Anita Walz, an open education, copyright, and scholarly communication librarian for University Libraries at Virginia Tech. “If this can help them learn faster or more thoroughly, I think it’s really exciting.”

Walz directs the grant program that funded the VR project, and she leads its open educational resource research agenda.

For four sessions so far this semester, Tucker has set up the VR equipment for Nappier's afternoon lab. He and Walz stayed to assist the veterinary students.

During a recent lab, Kathryn Strait, a first-year veterinary student, put on the VR headset to study where a dog’s heart and lungs are located.

“As a visual person, it’s helpful to have a 3D understanding of how each organ relates,” said Strait. “You can see how the spleen wraps around on the left side and how the heart is oriented.”

Eventually, Nappier hopes to have a few more VR sets for his labs. He also is working with Kiri Goldbeck DeBose, head of the veterinary medicine library, to add the VR equipment to the library for students to use anytime.

Additionally, using this VR technology, Tucker is developing an augmented reality (AR) dog that would be available as a smartphone app. Nappier presented the AR dog at a veterinary conference this past summer, and there was much interest, he said.

More funding is needed, however, to make the AR project a reality.

Canines are only the beginning for Tucker. With additional grant money, he said he’d like to develop VR versions of other animals, such as pigs and cattle.

For now, VR is changing the way that Virginia Tech veterinary students like Farthing are learning. Recently, as she gazed at a dog’s lung structure with the VR headset, she said she could picture where to place her stethoscope.

“I have a mental image now,” said Farthing, who in the future plans to work in a small animal veterinary practice alongside her mother, a veterinarian in Roanoke.

Written by Jenny Kincaid Boone

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)