Mike Evans uses his life’s experience to lead new School of Plant and Environmental Sciences

As director of the new School of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Mike Evans wants to create an environment where creative collaborations lead to innovative discoveries.

Mike Evans grew up in rural Pittsylvania County, Virginia, where he spent his summers pulling tobacco and running a soybean drill for his grandparents and neighbors.

He saved enough money during those hot summers to buy his first car — a 1980 Ford Pinto — which he proudly parked in the Cage during his first year at Virginia Tech. He’d been exposed to the university through his high school’s Future Farmers of America program, which brought him to campus to take part in horticultural competitions.

As a student majoring in horticulture, he fell in love with researching the plants he’d been surrounded by his entire life. The intensive laboratory work he did during his undergraduate years at Virginia Tech prepared him well for the rigors of graduate school at the University of Minnesota, where he earned a master’s degree and a Ph.D.

Evans went on to a career in higher education that involved research to help industries thrive, Extension outreach programs that impacted local communities, and academic programs that prepared the next generation of students for the challenges of facing the world.

Now, the Hokie alumnus has returned to Virginia Tech to use all the skills he’s acquired to lead the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences’ latest strategic initiative.

Evans is the director of the newly formed School for Plant and Environmental Sciences, which combines three former departments — horticulture; crop and soil environmental sciences; and plant pathology, physiology, and weed sciences — under one administrative roof.

“When we bring people together you get something new called ‘creative collisions.’ These intersections lead to innovation on a level that changes the paradigm of what is possible,” Evans said. “We want to create an environment in the school where the silos are broken down and people are interacting in unique ways to allow opportunities for more of these creative collisions to occur. This benefits everyone from students and professors to industry leaders and local producers.”

Though faculty and administration have been involved in planning the school via committees, public forms, and other outlets for three years, it becomes officially operational on July 1.

“Mike’s experience makes him the perfect person to lead the school and help our faculty, staff, students, and Extension professionals find new ways to work together to make an even greater impact on our college, the state, and the world” said Alan Grant, dean of the college.

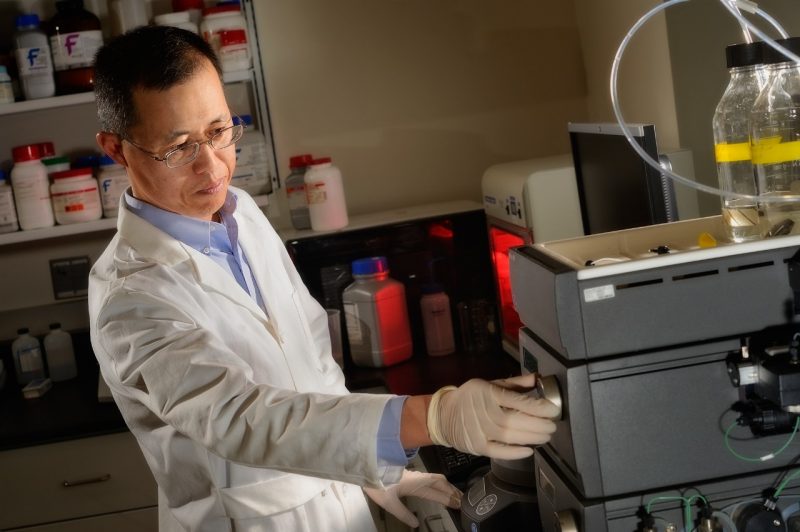

Evans most recently worked at the University of Arkansas, where he was an interim associate dean in the Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food, and Life Sciences. Prior to Arkansas, Evans was a professor at Iowa State University. At both institutions, he was a horticulture faculty member, teacher, and researcher who focused on controlled agricultural environments, such as greenhouses, and how to use hydroponic techniques to increase yields of food crops. He started his career as a researcher at the Gulf Coast Research and Education Center with the University of Florida where he conducted research and Extension programs related to greenhouse crops and ornamental plants.

Evans points to projects he did as a horticultural researcher that show how collaboration can lead to greater impact.

A few years ago, he was researching how lettuce is best grown in a controlled environment using hydroponics. He started to talk with a plant pathologist who was trying to find ways to combat powdery mildew on spinach. The two began to collaborate on ways to grow the spinach in a greenhouse, which allowed for faster growing cycles. This development in the greenhouse helped the plant pathologist do quicker scientific trials than it would have been possible in the field. The teamwork between disciplines was what made the solution possible.

“You never know what innovative, cross-disciplinary solutions are possible until you tear down the walls that exist and build a space where ideas can freely flow — and new ideas can be born,” he said.

Similarly, the school will merge three former departments and bring researchers, faculty, and staff together to use their diverse experiences and skillsets to tackle issues ranging from increased crop production to ways to grow healthier food throughout the world.

None of the majors or degrees offered by the three former departments will change, though Evans said the school will explore creating new majors that build upon the expertise of the faculty and meet the demands of students and industry. All clubs and student organizations will remain as they currently operate. The school also will focus on ways to expand the college’s physical footprint, such as constructing new greenhouses or the future Human and Agricultural Biosciences Building 2.

“I believe that by creating a space where new relationships can form and risk-taking in the name of innovation is encouraged, there is unlimited potential to make a lasting impact in plant and environmental sciences,” he said.