Researchers find that brain imagery shows difference between knowing or reckless behavior in criminal acts

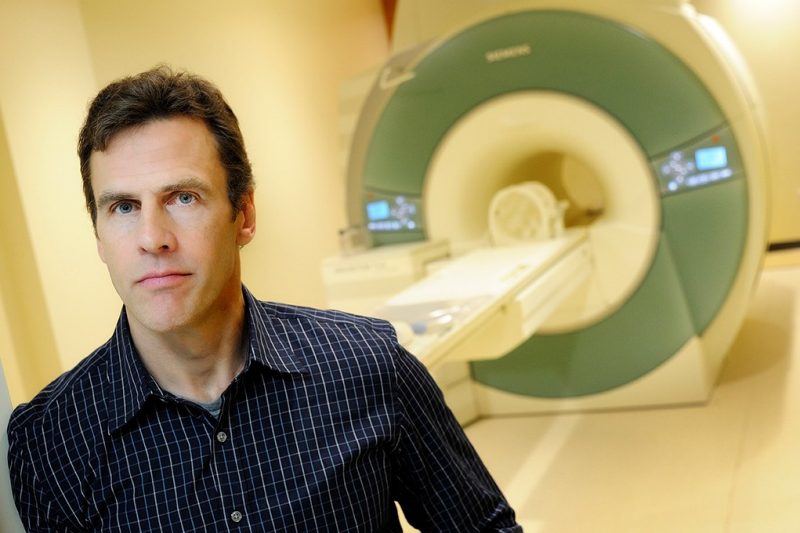

Read Montague, a computational neuroscientist at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, led a research team that discovered brain imaging can determine whether someone is acting in a state of knowledge about a crime.

Judges and juries always ponder whether people act “knowingly” or “recklessly” during criminal activity — and neuroscience has had little to add to the conversation.

But now, researchers, including computational neuroscientist Read Montague of the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, have discovered that brain imaging can determine whether someone is acting in a state of knowledge about a crime — which brings stiffer penalties — or a state of recklessness, which even in capital crimes such as homicide, calls for less severe sentences.

The discovery, scheduled for publication this week in the online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, will not have a bearing on court proceedings, but it is an inroad in the emerging field of “neurolaw,” which connects neuroscience to legal rules and standards.

In a brain imaging study of 40 people, researchers identified brain responses that indicated whether people knew they were committing crimes or if they were instead acting recklessly with the risk that they might be committing a crime.

The researchers provided the first neurobiological evidence of a detectable difference between the mental states of knowledge and recklessness, an exploration that historically has been confined to the courtroom.

“People can commit exactly the same crime in all of its elements and circumstances, and depending on their mental states, the difference could be one would go to jail for 14 years and the other would get probation,” said Montague, who is the Virginia Tech Carilion Vernon Mountcastle Research Professor and director of the research institute’s Human Neuroimaging Laboratory. “Predicated on which side of the boundary you are on between acting knowingly and recklessly, you can differentially be deprived of your freedom.”

The research was conceived under the direction of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience at Vanderbilt University and carried out by researchers at Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and Yale University.

Scientists scanned the brains of 40 subjects and asked them to decide whether to carry a suitcase across the border, varying the probability that the suitcase contained drugs.

Using noninvasive functional brain imaging and machine-learning techniques, in which a computer learns to find patterns in data, the scientists accurately determined whether the research subjects knew drugs were in the case, which would make them guilty of knowingly importing drugs, or whether they were uncertain about it, which would make them innocent.

The researchers showed that knowing and reckless mental states corresponded to detectable neurological states, and that those mental states can be predicted based on brain imaging data alone. However, the researchers cautioned that the assessment of the mental state of a defendant should not be reduced to the classification of brain data.

“In principle, we are showing these brain states can be detected when the activity is taking place,” Montague said. “Given that, we can start asking questions like, which neural circuits are engaged by this? What does the distribution look like across 4,000 people instead of 40 people? Are there conditions of either development, states of mind, use of pharmacological substances, or incurred injuries that impinge on these networks in ways that would inform the punishment?”

The study was informed by a judge and researchers at Vanderbilt University, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Virginia, the University of Kentucky, and the Ohio State University.

“Scientists and lawyers speak different languages,” Montague said. “A translation goes on when you bring these groups together that gives new meaning to interdisciplinary. Lawyers think of people as being conscious and deliberative, and the law sees people that way — you are an independent agent and you make choices for yourself. That picture ignores the scientific fact that 99 percent of the decisions made in your nervous system never make their way to consciousness. You are being driven by things to which you don’t even have conscious access — that difference was something we had to work through to design the experiment.”

The study was supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to Vanderbilt University, with a subcontract to Virginia Tech. The Wellcome Trust, the Kane Foundation, the Brown Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute also provided support.