Powered by magnets, energy harvester converts wasted heat into electricity

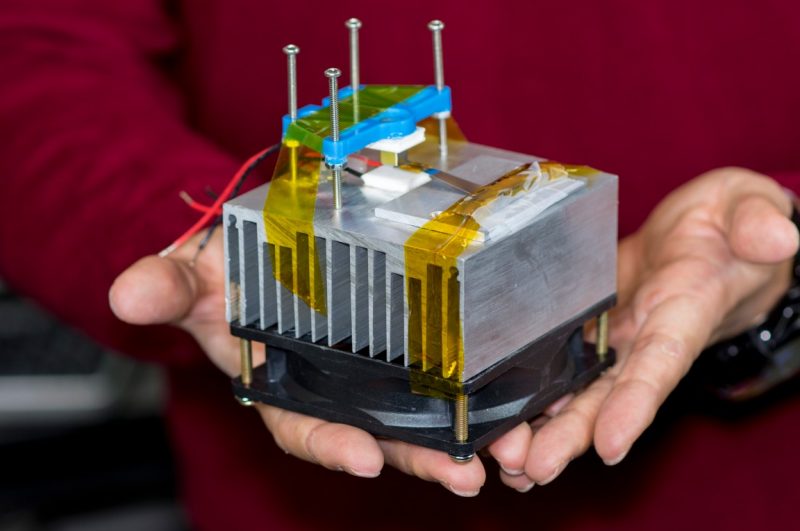

Postdoctoral researcher holding a thermal energy harvester, a device which converts wasted heat to electrical energy.

Researchers at Virginia Tech have built a device that uses a pair of magnets and a piezoelectric lever to convert wasted heat to useful electricity.

The system is the first working, bulk-scale example of a thermo-magneto-electric generator, a new type of thermal energy harvester designed to operate efficiently without the large temperature gradients required by most systems.

Thermal energy harvesters recover waste heat, a significant source of energy loss in homes, manufacturing plants, and vehicles. Energy seeps out of mechanical systems from hot surfaces and exhaust gases and dissipates into the environment.

“You can take any mechanical process around you, like running your lawnmower or a car, and about 40 to 60 percent of the energy you’re putting in as electricity or gas is wasted as heat. It’s a huge loss,” said Shashank Priya, the Robert E. Hord Jr. Professor of Mechanical Engineering in the College of Engineering and associate director for research and scholarship at the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science, who led the study. “There’s a lot of interest in capturing that heat, which now gets discarded.”

Converting some of the lost heat to electricity would lower overall fuel consumption, cutting costs and blunting environmental impacts. By siphoning off heat more quickly, it would also increase the performance of systems with electrical components, which operate more efficiently at lower temperatures.

The new thermal energy harvester, described in a study published in Scientific Reports, brokers the conversion of heat to electricity by taking advantage of materials called soft magnets, which are easily magnetized and demagnetized.

One such material is gadolinium, which is magnetic at around room temperature, but loses its magnetism as it warms up.

In Priya’s energy harvester, a gadolinium soft magnet is attached to a flexible plastic cantilever. A hard, or permanent, magnet rests against the heat source — for example, the hot surface of a computer’s CPU. Magnetic attraction pulls the two magnets together, allowing heat to flow from the hard magnet into the soft magnet. This heats the soft magnet above its transition temperature, and it becomes nonmagnetic.

Without magnetic attraction to bind it to the hard magnet, the soft magnet is pulled away by the cantilever. Separated from the heat source, the soft magnet cools down; the drop in temperature reactivates its magnetic properties, starting the process over again.

Pulled in one direction by the hard magnet, and the other by the cantilever, the soft magnet cycles up and down as it gains and loses magnetism. Meanwhile, it absorbs heat from the hot surface via the hard magnet, cooling it and dispersing the thermal energy into the environment, which acts as a heat sink.

But the energy contained in the heat is recycled, because the piezoelectric cantilever converts the soft magnet’s up-and-down motion into electricity that can be used or stored.

One of the key advantages of the device is that it effectively harvests thermal energy from heat sources not dramatically hotter than the ambient air — the kind most common in homes and industrial plants.

“If you look around, you see mostly low-temperature gradients,” Priya said. “But at low temperatures, there aren’t many promising solutions.”

In tests, the researchers used their device to harvest thermal energy from heat sources around 70 to 80 degrees Celsius. The device operating temperature is mainly governed by the heat required to demagnetize the soft magnet; with currently available materials, it can be as low as 50 to 60 degrees Celsius.

The new energy harvester’s ability to operate at moderate temperatures — along with its compact size and mechanical simplicity — could make it practical for household use. Priya envisions that the heat emanating from everyday appliances could be used to power networks of sensors in data-driven “smart” homes.

“There are a lot of places where even a watt of electricity is sufficient, if you want to run a sensor node,” Priya said. “Let’s say you want to monitor some process, like measure a temperature or a fluid flow or pressure change. All you need is a burst of thermal energy available to you in a periodic manner.”

The researchers are scaling up the thermal energy harvester to increase its electrical output, refining the materials and design, and adapting it for specific applications.

The study’s first author is Jinsung Chun, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. First-year doctoral student Ravi Kilgore, who holds a Doctoral Scholars Fellowship from the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science, and other graduate students in the department of mechanical engineering also worked on the project.