More study needed to clarify impact of cellulose nanocrystals on human health, researcher reports

Are cellulose nanocrystals harmful to human health? The answer might depend on the route of exposure, according to a review of the literature by a Virginia Tech scientist, but there have been few studies and many questions remain.

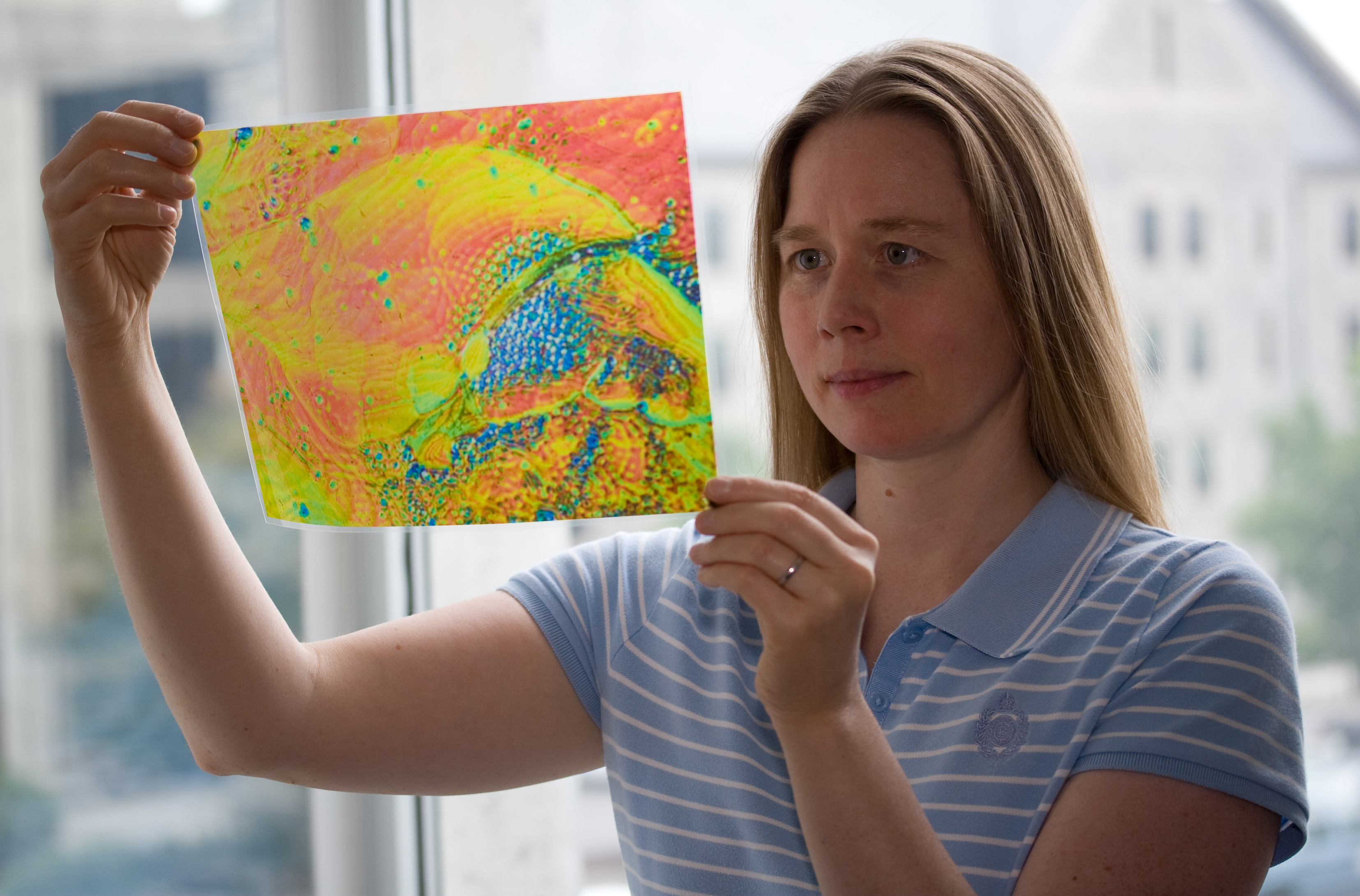

Writing in the journal Industrial Biotechnology, Maren Roman, associate professor of sustainable biomaterials in the College of Natural Resources and Environment, pointed out discrepancies in studies of whether cellulose nanocrystals are toxic when inhaled or to particular cells in the body. She said more studies are needed to support research results that the nanocrystals are nontoxic to the skin or when swallowed.

Cellulose nanocrystals are produced from renewable materials, such as wood pulp. Biocompatible and biodegradable, the low-cost, high-value material is being studied for use in high-performance composites and optical films, as a thickening agent, and to deliver medicine in pills or by injection. But before a material can be commercialized, its impact on the environment and human health must be determined.

Roman, also associated with the Macromolecules and Interfaces Institute at Virginia Tech, reviewed published studies about the effects of cellulose nanocrystals on the respiratory system, gastrointestinal system, skin, and cells.

In the respiratory system, the body can clear particles from the throat and nasal areas by moving them toward the mouth. Particles are removed from the lungs through engulfment and degradation or movement upwards, depending on particle size and surface charge.

Early studies found tissue damage and inflammation depended on dose and specimen form —– dry powder versus suspension in a carrier liquid. A later animal study showed no ill effects from inhaled particles, but Roman pointed out that the size, shape, and surface charge of the particles were unknown.

Most studies of nanoparticles’ effect on the gastrointestinal tract — mouth, esophagus, stomach, and intestines — have shown that the particles pass through and are eliminated, Roman reported. However, some studies demonstrated that nano- and microparticles can penetrate the protective barrier of the intestine and reach the bloodstream.

Roman described the cellulose nanocrystals properties — size, electrostatic properties, molecular structure, and pH — that make their penetration unlikely but noted that there have only been two studies published on oral toxicity specifically of cellulose nanocrystals.

Most studies of nanoparticle skin exposure reported no unintentional permeation of nanoparticles through the outer layer of skin. The three published studies of cellulose nanocrystal toxicity upon skin exposure showed cellulose nanocrystals not to cause any skin sensitization skin tissue damage.

What if a nanoparticle reaches the cells, such as in the brain? Most studies also showed that cellulose nanocrystals are not toxic to cells, depending on the dose. The most serious impact was a 20 percent loss in viability of liver cells in rainbow trout.

Studies also looked at cells from humans, such as from the brain, throat, and eye, and from other animals. “The discrepancies in the results are not surprising,” said Roman, “considering that the studies all used different cell lines, cellulose sources, preparation procedures, and post-processing or sample preparation methods.”

She was also critical of much of the research for overlooking chemicals that may be present in cellulose nanocrystals from prior processing.

“Only by careful particle characterization and exclusion of interfering factors will we be able to develop a detailed understanding of the potential adverse health effects of cellulose nanocrystals,” Roman concluded.