Summer undergraduate research: The search to unravel a historic secret

Two undergraduate students are using research to try to unravel a historical secret lost centuries ago that has wide ranging implications for our future, including lighter – and therefore more fuel efficient – cars as well as more powerful reactors for energy.

Damascus steel, which was manufactured in the area that is now Syria as far back as A.D. 900, was known for its overwhelming strength and sharp blade, while also being capable of bending without breaking. The metal has a distinct, wavy pattern. While sword smiths have been able to replicate the appearance of Damascus steel, they have not been able to reproduce its other properties after those who made it died hundreds of years ago without passing on the process.

Researchers recently analyzed ancient Damascus steel museum pieces and found the material contained carbon nanotubes – cylindrical structures made up of a highly structured form of carbon – evenly dispersed through the metal. The discovery may be part of the puzzle. At the same time in the laboratory of Barry Goodell, professor of sustainable biomaterials in the College of Natural Resources and Environment, another discovery showed carbon nanotubes could be formed from wood and plant fibers.

“Carbon nanotubes can be made in a variety of ways,” Goodell said. “What we want to find is how they can be incorporated into steel, and not just in, but also aligned and dispersed.”

Two undergraduates are tackling that mystery under Goodell’s guidance this summer through the Scieneering program: Veronica Kimmerly, a senior majoring in chemical engineering in the College of Engineering and mathematics in the College of Science, and Beck Giesy of Sterling, Va., a sophomore also majoring in mathematics.

Goodell and three other faculty members – Alan Druschitz, associate professor of materials science and engineering; Scott Renneckar, associate professor of sustainable biomaterials; and Xinwei Deng, assistant professor of statistics – are leading the project. “The benefits this high-risk project has for you [Veronica and Beck] is that you may strike on a method that works and then be famous,” Goodell told the students. “But that high risk also means there is a 95 percent chance that it won’t happen,” he said with a smile.

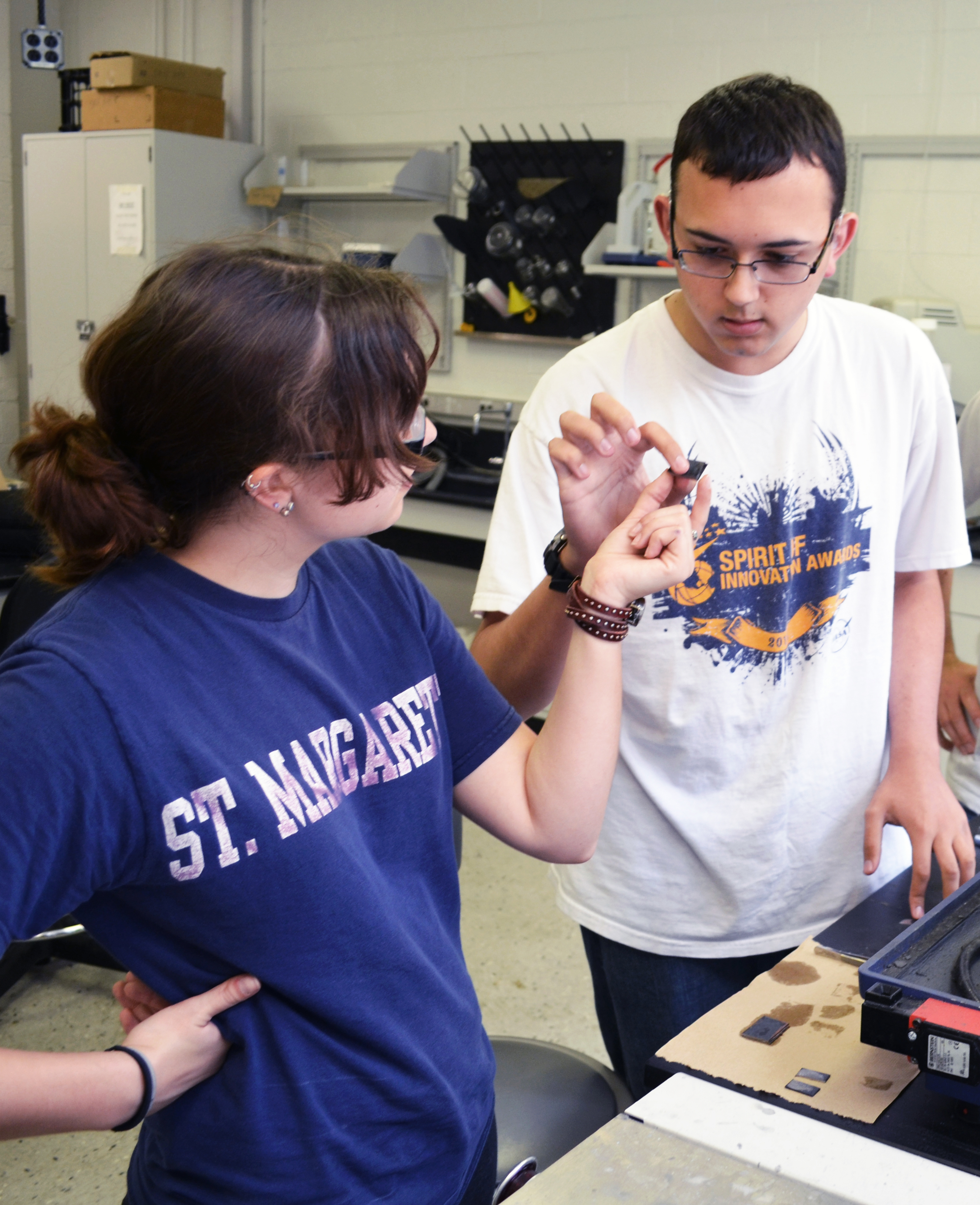

No matter the final outcome, the students are gaining a wealth of knowledge and experience. “We are trying to make samples by pressing pre-carbonized wood fiber in between steel plates,” Kimmerly said. “Basically, we are forming carbon nanotubes and then trying to press them into the steel.”

A few weeks into the experience, Kimmerly and Giesy have created samples using a roll press, creating metal pieces with constant pressure across for a consistent sample.

For some more practical skills, but not for samples to test, they also went to the university’s foundry to hammer out some pieces. “It is one of those life skills. If you are offered the chance to go do some blacksmithing, you say yes!” Kimmerly said.

The experience has helped stretch the students’ boundaries for a positive learning experience. “The purpose of Scieneering is to do interdisciplinary research,” Giesy said. “I decided to take that to the extreme and do something I had absolutely no idea about. With nanotubes, this whole process is about chemistry on a micro-molecular level, which I don’t know much about – I’ve just taken basic chemistry so far. I am learning it as I go and it makes it fun.”

Once the Damascus steel secret is revealed through research, Goodell said it has the potential for wide-ranging benefits. The steel could be used to make cars, making them lighter for better fuel efficiency while also maintaining strength for safety. In addition, steel reactors could run at twice the temperature of current reactors, creating more efficient output of energy.

During the summer of 2013, more than 250 students are taking part in undergraduate research experiences through more than a dozen programs on campus. The Office of Undergraduate Research is coordinating workshops and activities for the programs' participants through the summer. Students will present their work at the Virginia Tech Summer Undergraduate Research Symposium on Wednesday, July 31.

Dedicated to its motto, Ut Prosim (That I May Serve), Virginia Tech takes a hands-on, engaging approach to education, preparing scholars to be leaders in their fields and communities. As the commonwealth’s most comprehensive university and its leading research institution, Virginia Tech offers 240 undergraduate and graduate degree programs to more than 31,000 students and manages a research portfolio of $513 million. The university fulfills its land-grant mission of transforming knowledge to practice through technological leadership and by fueling economic growth and job creation locally, regionally, and across Virginia.