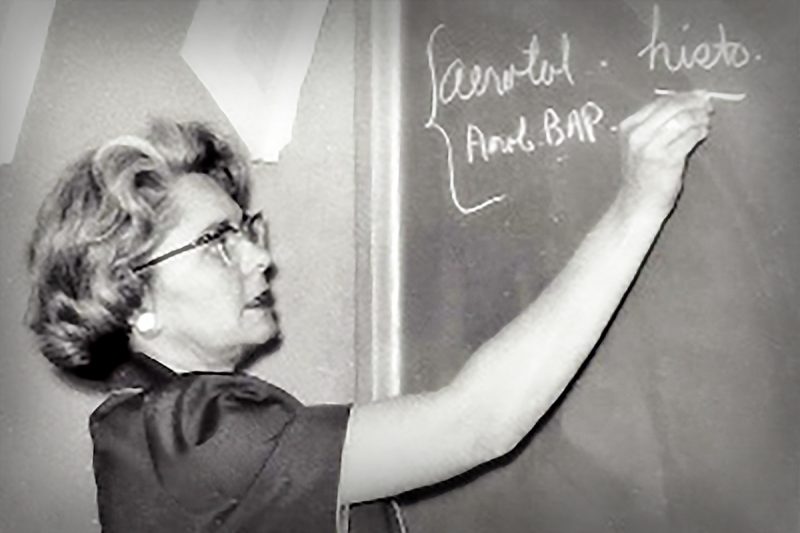

In memoriam: Lillian Haldeman 'Peg' Moore, University Distinguished Professor

Lillian Haldeman “Peg” Moore, age 91, passed away on Nov. 21, 2020.

After working for 15 years at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Peg Moore began work at Virginia Tech in 1966 as a professor of bacteriology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

She was instrumental in setting up the Anaerobe Lab and served as the associate director. Moore was an authority in the field of anaerobic bacteriology, food microbiology, and was a pioneer in the field of microbiome research.

“Peg Moore put microbiology and Virginia Tech on the map. She was intelligent, kind, and a hard worker,” said Dennis Dean, University Distinguished Professor and founding director of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute.

Moore was awarded the title of University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech for contributions to anaerobic bacteriology research worldwide. She received grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and NASA, which enabled Virginia Tech to become a major recognized research institute in the area of bacteriology and veterinary sciences.

Those who have been around campus long enough know that Virginia Tech’s rich microbiology history can be traced back to that special gem: the Anaerobe Lab.

Constructed on Price’s Fork Road in 1970 as an extension to the veterinary sciences building, the lab housed 60,000 cultures of anaerobic bacteria isolated from humans and animals. Anaerobic bacteria do not live or grow well when oxygen is present, and little was known about them before the lab was established.

Peg Moore and W.E.C. “Ed” Moore, a professor in Veterinary Sciences, quickly changed that when they led the charge to create the facility.

They met at an American Society of Microbiology meeting in the late 1960s, when Peg Moore (then “Haldeman”) was employed at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia.

Impressed by her expertise in botulism, Ed Moore recruited her to come work with him at Virginia Tech, where he studied anaerobic bacteria living in the intestinal tracts of humans and animals.

Together, they envisioned an Anaerobe Lab devoted to the study of anaerobes of all types from all angles. They relentlessly applied for funding for three years until they secured a grant from the National Institutes of Health and their dream came true.

The first thing that the Moores did after moving into their new space, which included a teaching lab and eight research laboratories, was hire other scientists who were experts in the field.

Tracy Wilkins, a scientist and entrepreneur who would go on to become director of the Anaerobe Lab in 1985 when the Moores married, came in 1972. In 1985, Wilkins hired Dennis Dean, who would later become the founding director of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute at Virginia Tech.

“The Anaerobe Lab became famous pretty quickly. Hundreds of people came from all over to train and study human and animal intestinal anaerobic bacteria. Peg and her husband were the first to show the importance of the intestinal microbiome and made great strides in elucidating how anaerobic bacteria cause disease,” said Wilkins, University Distinguished Professor Emeritus.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Anaerobe Lab team quickly became internationally known as the “go to” group for anaerobic microbiology. With a grant from the National Cancer Institute, they studied populations of intestinal bacteria related to colon cancer, investigating the link between cultural diets and disease. With a grant from NASA, they determined that people isolated in space capsules do not exchange bacterial communities.

The team isolated tens of thousands of their own strains of bacteria for the collection and also acquired three historical collections from Prevot at the Pasteur Institute, Ivan Hall, and Leland McClung.

Scientists worldwide consulted a manual that the Moores developed with instructions for how to isolate, grow, and identify anaerobic bacteria. They also taught an annual two-week training course for more than 15 years.

The Moores' research helped lay the groundwork for building the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine on the Virginia Tech campus.

“I was truly fortunate to get an offer to join the Department of Anaerobic Microbiology. The environment for developing and sustaining a microbiology research team, which included a combination of undergraduate and graduate students, was made up of a special community of scientists. Peg Moore, Ed Moore, and Tracy Wilkins were close and remarkably unselfish and supportive colleagues from my home department, the Anaerobe Lab. This special group of people enriched my career in many ways,” said Dean.

Peg Moore studied zoology at Duke University, with an eye on attending medical school. She graduated from Duke University in 1951. She was then employed by the CDC, working various lab positions and learning bacteriology on the job while working toward a professional rating taking night classes at the University of Georgia. Eventually she began working with diagnostic reagents, which entailed making standard reagents for use by state health departments. She graduated from Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana, with a Ph.D. in 1964. After working for 15 years with the U.S. Public Health Service's Communicable Disease Control Laboratory in Atlanta, Peg was employed by Virginia Tech until she retired in 1996.

Peg Moore was preceded in death by her husband, Ed Moore. She is survived by three stepsons, Howard Moore, of Stanardsville, Virginia; Jed Moore, of Mesa, Arizona; and David Moore, of Ft. Lauderdale, Florida; and their families.