Flint residents 'did nothing to deserve this'

With the nation focused on Flint, Michigan, for all the wrong reasons — a tainted water supply, denial of a public health crisis, and children exposed to lead — Virginia Tech engineering faculty and student researchers on Thursday talked about how they helped expose the problem and what would happen next.

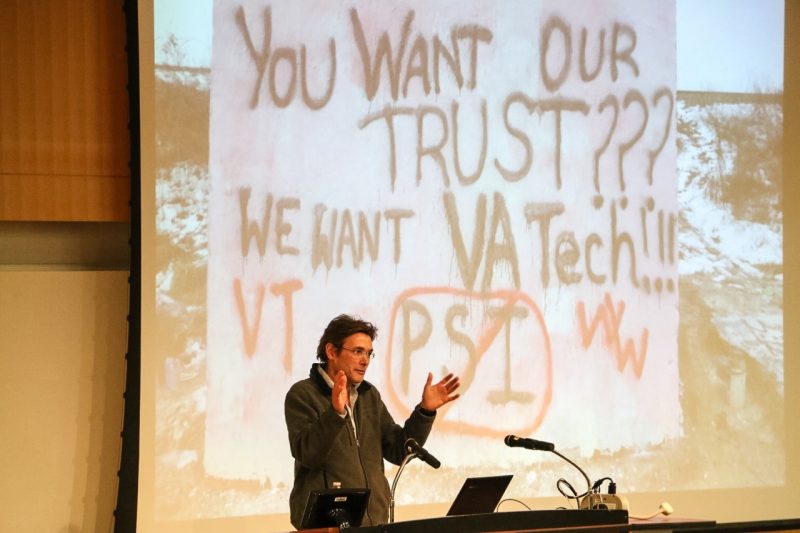

More than 500 people filled the Quillen Family Auditorium and two overflow rooms at Goodwin Hall in Blacksburg to listen to a group of students who stood by the residents of Flint — affectionately known as “Flintstones” — and a mother who summoned Virginia Tech to a town that local and state officials had mostly abandoned. More than 1,900 people watched a livestream broadcast.

“The most powerful force in the universe is a mother worried about the health of her child,” said Marc Edwards, the Charles Lunsford Professor of civil and environmental engineering.

LeeAnne Walters, a concerned, stay-at-home mother who could not get state or local officials to pay attention to the orange-tinted water coming out of her spigots in Flint, kicked off the Virginia Tech-Flint alliance when she called Edwards.

Thursday, Edwards presented her with an “alchemy award” — a lead ring cut from a pipe which he had, more than a decade ago, taken out of a child’s home in Washington, D.C. The 2005 fight in Washington was the same. Residents were in need, officials were denying the presence of lead.

He said the child was born in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“I found the pipe in 2005 and I said I would never let this happen to another child, so help me,” Edwards said. “Ancient alchemists tried to turn lead into gold. Your efforts really avoided a major tragedy. I know that you do not want another piece of lead in your life, but it came from a pipe that was in a house of a child in Washington, D.C.”

A gold chain was laced through the ring, making a necklace.

“It’s been a long journey,” Walters said. “Thank you to Marc and the students at Virginia Tech, but the thanks isn’t just from me. It’s from all the people of Flint. The fact is, they cared more about us than the city and the state, and it is something we will always hold close to our heart.”

Edwards and his students sent bottles to collect water samples to Flint residents and took four trips to Michigan from August to October.

“We sent out 300 kits to Flint, each one with three bottles,” said Anurag Mantha, a graduate student in civil and environmental engineering. “We took over from there and coordinated the analysis. We were hoping there was not a problem, that there was nothing wrong in Flint. Once we analyzed the samples, it was clear that something was desperately wrong.”

The lead levels were off the charts and the water was visibly full of debris.

“Flint water was like looking at a snow globe, there were so many particles in it,” said Christina Devine, a graduate student.

“We were extremely concerned,” said William Rhoads, a doctoral student in civil and environmental engineering. “On average there was 133 times more lead in her water than the maximum allowable.”

They tried to convince state and city officials that the water was hazardous, and filed Freedom of Information requests to compare agency findings with those of Virginia Tech.

“For 18 months, 10,000 residents were exposed to toxic water,” said Siddhartha Roy, a civil engineering graduate student. “They did nothing to deserve this. Nine thousand kids were exposed.”

Roy, as did many of the presenters, had to choke back emotion. He described a call he received from a woman who was in tears, because she had given her children and grandchildren tap water.

“She told me she poisoned her kids,” Roy said. “It wasn’t her fault. But a mother’s heart could never accept that. She thanked all of us for what we did. This is why we spent the last six months of our life pulling all-nighters, pulling weekends together, because we cared. It changed who we are as human beings.”

The researchers dedicated their work to the citizens of Flint, with respect.

“You can just be a normal person fighting for a just cause,” said Ni “Joyce” Zhu, a graduate student. “You don’t have to be a president or have a title, just a just cause. We thank the Flint residents, the Flintstones.”

Provost Thanassis Rikakis called the work a stellar example of Virginia Tech’s vision of what a 21st century land grant university should be doing — research in a real-world context, with Flint as the classroom.

Earlier this week, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder named Edwards and the Virginia Tech team to “Flint Water Interagency Coordinating Committee,” tasked with finding a long-term strategy to address the water crisis.

“No one in Flint trusts the government,” Roy said. “Flint residents now only trust a group of 20-somethings, a 19-year-old, and a professor in Blacksburg.”

Written by John Pastor.