At the touch of a finger: Virtual patient helps students learn anatomy

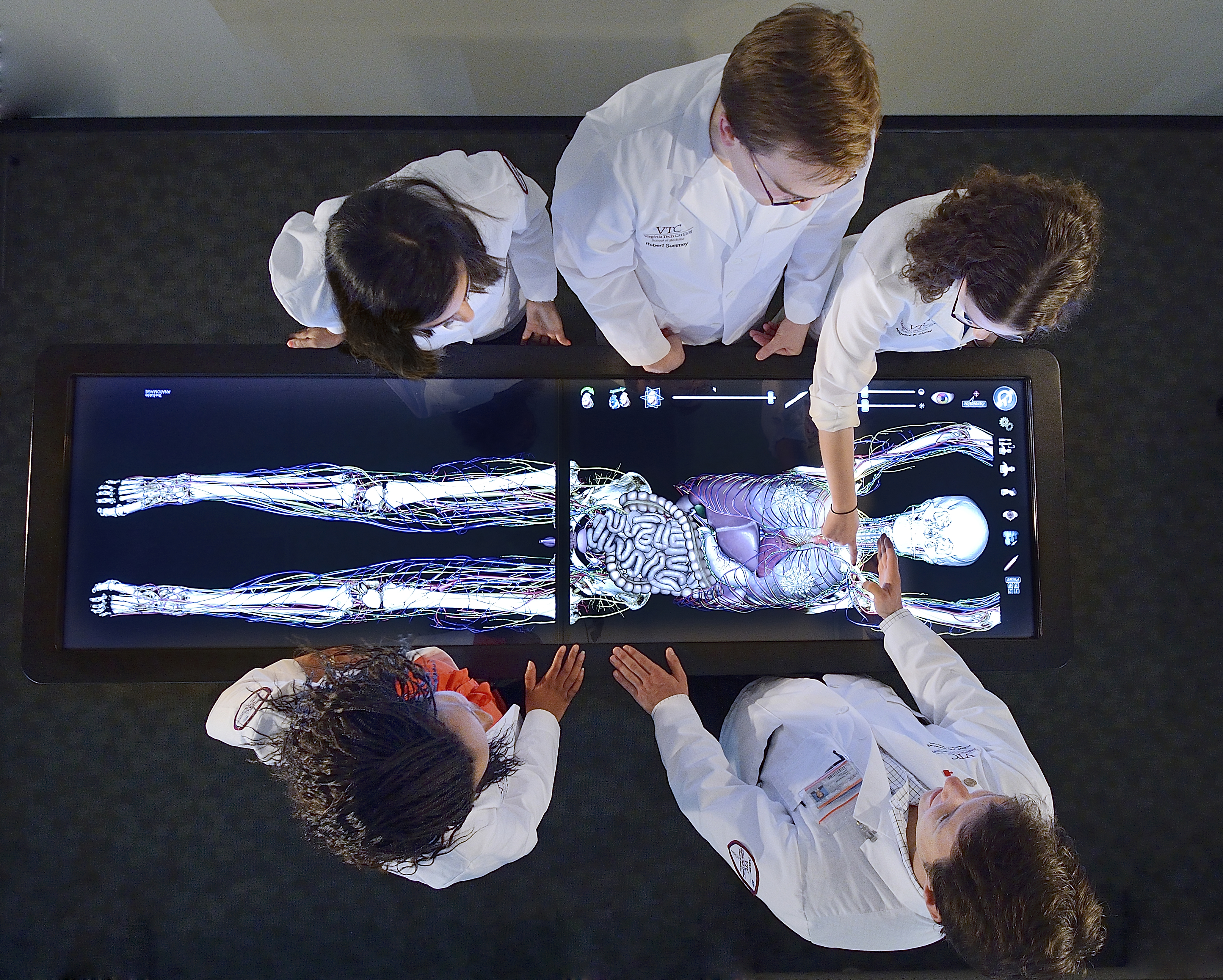

One of the anatomy labs at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine was hushed the other day, hushed except for the soft voices of a dozen faculty members clustered around a six-foot-long table at the front of the room.

From a distance, they almost resembled a surgical team. Upon closer inspection, however, the focus of their quiet intensity became clear: a virtual patient embedded in the table’s electronic display. The group was being trained on a system that would enable them to teach anatomy like never before.

The table’s maker – Anatomage – enhances traditional anatomy instruction with modern computer and imaging capabilities. The result is a simulated high-tech operating table complete with virtual life-sized patients, touch-screen navigation, and a computer software system that has seemingly endless applications.

Anatomage was founded in 2004 as a company specializing in 3-D imaging software. Today the system has expanded into a variety of markets such as orthodontics, dental implants, radiology, and medical device design. For the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, the table’s primary purpose is to teach anatomy to first- and second-year students. In a TED Talk demonstration in San Jose in 2012, company president Jack Choi called the application “dissection without a cadaver.”

The system features a natural intuitive interface. Much like an iPad, the table is operated by the swipe of a finger. Layer by layer, a computer image of a human body built upon real medical imaging scans can be peeled away – the skin, the muscles, the skeletal system, the organs – revealing a look inside the human body that is unmatched by cadavers or textbooks. The image can be rotated and enlarged. A scalpel tool allows the user to slice, layer, segment, and cross-section the image in any number of configurations. The user can quickly and easily make changes and readjust to hundreds of different views and scenarios.

In a study of the heart, for example, the user might begin by removing the image’s skin, soft tissue, muscles, and skeletal system. With a tap of the screen, the user might then mask out all the organs except the heart. A splice of the heart with the virtual scalpel opens it up to a cross-sectional view. A quick magnification reveals minutia of the organ’s chambers.

From there, desired views of the heart can be saved on the system itself or to an external storage device. Faculty members can customize views for specific assignments and lectures, and students can download those views for later study.

“This is a breakthrough in medical education,” said Dr. Cynda Johnson, dean of the school. “Through interactive learning, the Anatomage system helps our students grasp the spatial relationships of anatomy and the locations of hard-to-identify structures. The students are better able to visualize how systems in the human body work together.”

Dr. Carol Gilbert, an associate professor in the school’s Department of Surgery, said the table is not designed to replace other traditional learning tools – such as cadavers – but to supplement them.

“Students learn in different ways,” she said. “The anatomy table is one of many learning tools we provide. Our goal is to graduate well-rounded, confident physicians.”

The Anatomage system’s library is filled with more than a hundred real-life conditions and illnesses. In addition, faculty can add cases of the actual patients the students are studying, thus creating the school’s own medical case library.

“With this capability, the table is more than just a 3-D anatomy textbook,” Gilbert said. “It’s an opportunity to develop our own curriculum.”

In fact, the system’s first local case – a BB gun injury to the brain – was loaded within days of the patient’s arrival at Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital’s trauma center.

“There’s a lot you can do with this system,” Gilbert said. “It really empowers our teaching.”

Another feature enables users to make a computerized viewer of medical imaging scans, so students can scroll through typically hundreds of views of a scan to understand where a problem is and how it relates to various systems in the body.

“Before, this wasn’t possible logistically because of the huge file size,” Gilbert said. “Now students can look at real scans as opposed to just slices. It makes human anatomy so much more comprehensible – and real – for the students early on.”

Students and faculty aren’t the only ones using the system. The anatomy table will be featured at the school’s inaugural mini medical school, Anatomy for Artists and Other Curious Sorts, which will be open to the public on four consecutive Tuesday evenings beginning March 11.