A critical component for future physicians

During the past few years, students from across the country have converged on Roanoke to join the inaugural classes of the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. Now, only a few years after the first class’s arrival, many students are setting out across the world.

But they aren’t traveling as doctors – at least not yet.They’re traveling as scientists.

The Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine is one of the few medical schools nationwide that places an emphasis on original research throughout the four-year curriculum. By teaching research fundamentals during the first year and providing dedicated time for research throughout the remaining three, students are set on track to practice and contribute to evidence-based medicine.

Rather than relying on potentially outdated standards of care or those without sound scientific foundations, these future doctors will delve into the latest research findings, enabling informed clinical practices.

“Spending time on research is a hard sell for students preparing for board exams,” said Leslie LaConte, director of research education at the medical school and an assistant professor in the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. “But once they see that their board exams went well and they have the beginnings of a publishable research paper, they get excited. Plus, as residency programs expect trainees to do more research, contributing to the body of medical science and publishing their findings will help our students find positions.”

Besides educating students as problem-solving physicians and distinguishing them among residency applicants, the curriculum’s emphasis on research produces valuable original scientific data. Students coauthor peer-reviewed papers and travel the globe presenting their research at scientific conferences. Within the past year, multiple students have made presentations to the interest of peers from many institutions.

“It was rewarding to see that our research was well received and plays a part in the greater scientific world,” said Matthew Levine, a fourth-year medical student who presented his research at a poster session during the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians in Denver, Colorado. “Having other scientists interested in our work was encouraging.”

“The experience was excellent,” echoed Levine’s partner on the project, fourth-year medical student Andrew Moore. “It was great getting research from an emerging medical school placed alongside that from heavy hitters like Yale, Stanford, and the University of Michigan. The reason I came to VTC was because of its emphasis on research.”

The two have worked with Dr. Damon Kuehl, a physician in the Carilion Clinic Department of Emergency Medicine and an assistant professor in the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, on research focusing on resource utilization in emergency departments.

Previous studies had investigated how different emergency departments administer such resources as high-tech scanning equipment, the use of which skyrocketed 330 percent during the past two decades. But none have looked at the question on a physician-by-physician scale.

Some doctors order expensive diagnostic tests at much higher rates than their peers. Understanding the underlying causes for these variations could help curtail the highest users, potentially leading to savings of up to $600,000 per physician.

Besides analyzing ways to save money, students are conducting research into saving lives.

Fourth-year medical student Joshua Nichols, for example, is working with Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute Assistant Professor Sarah McDonald to develop a fast, inexpensive method for genotyping samples of rotavirus, which infects nearly every child around the world before the age of five.

In industrialized countries, the virus leads to little more than stomachaches and diarrhea. In developing countries, however, the virus often proves lethal, accounting for the death of more than 450,000 children worldwide each year.

Nichols developed a method to screen samples of rotavirus to determine how often different strains swap genes and create new varieties. Using contacts provided by his mentor McDonald and Dr. Colleen Kraft, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, he visited the University of Cape Coast in Ghana with graduate student Allison McKell to pitch the idea of collecting rotavirus samples, identifying logistical hurtles, and establishing a working relationship with the citizens and health care providers there.

Once the samples are taken, Nichols will receive them for screening and analyzing their genetic variance. Although much work remains, he has already presented his screening method at the International Symposium on Double-Stranded RNA Viruses in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“Being able to present my poster was cool,” said Nichols. “People from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were interested in my work, as were investigators from other countries.”

The students credit their successes to the emphasis placed on research early in the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine curriculum. While the first year focuses on teaching the fundamentals and exposing students to original biomedical research literature and the rationale that goes into successful studies as well as to research opportunities available to the students, the second year provides dedicated time for research.

The students’ projects culminate with a school-wide poster event, with oral presentations featuring those earning Letters of Distinction, an honor that will help students stand out among other residency applicants. And while their research papers will contribute to the scientific literature, the real value of the students’ projects rests in the skills they will have for the rest of their careers.

“I had done research in psychology before, but this was my first time doing bench research,” said Katherine Dederer, a fourth-year medical student. “I had a lot to learn but everyone was very helpful in teaching me the techniques I needed. I don’t know if I will continue with my current line of research, but I can carry the skills I learned into my next project, no matter what specialty it’s in.”

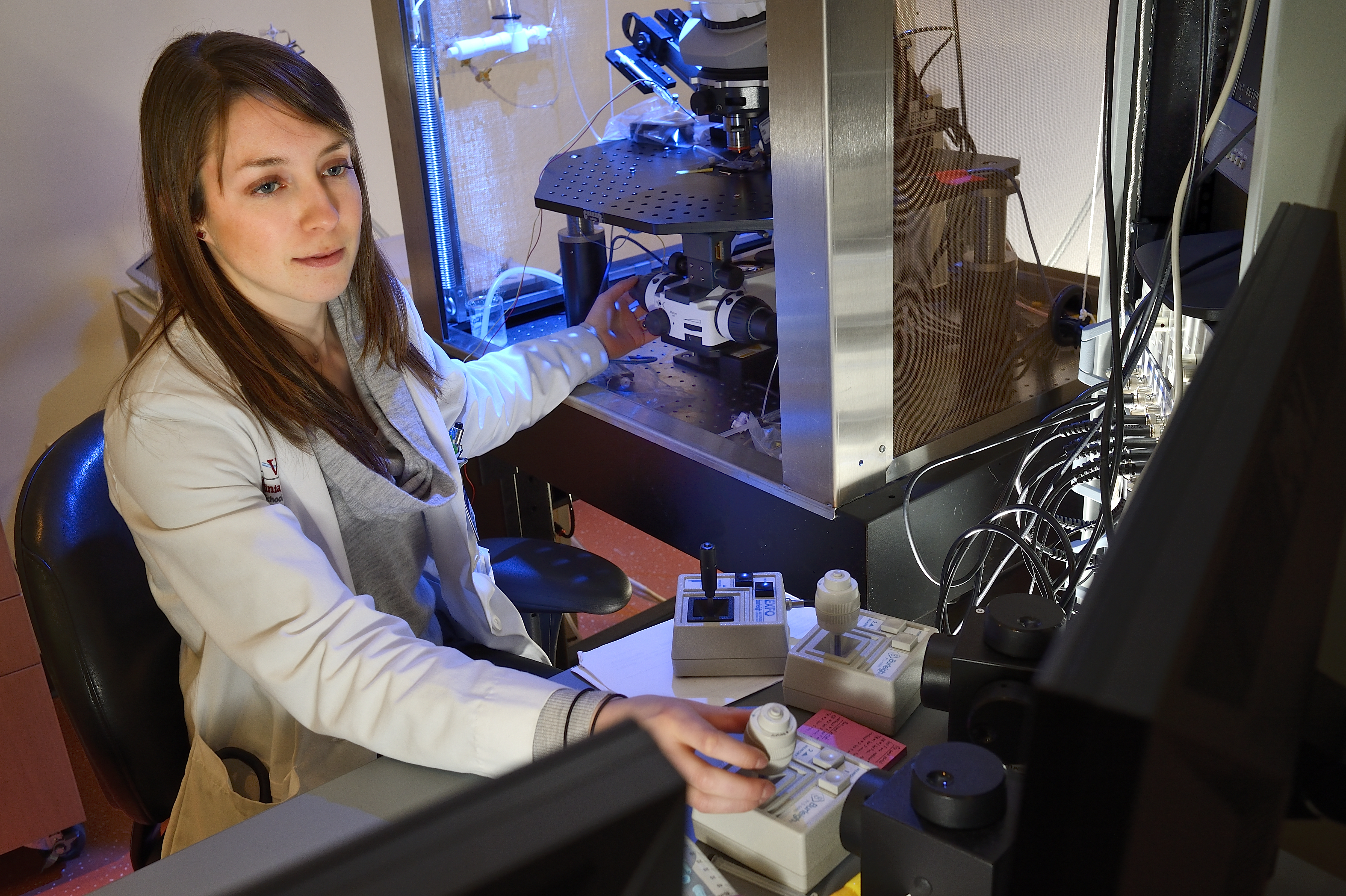

For her project, Dederer joined Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute Executive Director Michael Friedlander’s laboratory to help conduct studies of how noisy patterns of electrical signals from the brain’s inhibitory nerve cells are transferred through the cerebral cortex. Such an analysis enabled Dederer to be among a small group of biomedical investigators who are trying to determine how realistic information that is often imprecise and noisy is relayed in the living brain.

In most laboratory experiments, the analysis of information transfer is limited to precise and regular patterns of activity and usually within the context of the more easily studied cases of excitation. But true to the mission of the Virginia Tech Carilion medical student’s research experience, Dederer, along with the help of research assistant professors Quentin Fischer and Hodja Kalikulov, took on the more complicated problem of inhibition and realistic messy patterns of electrical signaling.

“This is just the type of bold translational approach that is needed to move from the well-controlled lab setting in order to address real brain disorders, such as seizures, Parkinson’s disease, and psychiatric disorders,” Friedlander said. “With the increasing importance of new therapies that chronically stimulate the brain, it is essential that we are able to understand and apply the most effective and safe parameters to patients.” The analysis of the communication of patterned inhibitory signals is interesting to many scientists and physicians, including those who spoke with Dederer during her presentation last fall at the Society for Neuroscience’s annual meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Presenting their original research findings at scientific and medical conferences, however, is only one way students can share their results. Another is to coauthor an original research article published in a peer-reviewed journal, which is what Andrew Demmert accomplished last fall.

Demmert worked in the laboratory of Deborah Kelly, an assistant professor at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. There Demmert helped install a new software program for the 3-D reconstruction of molecular imaging using electron microscope tomography.

After investigating how other laboratories apply the software, Demmert configured and optimized the program for the institute’s infrastructure. Thanks in part to these efforts, an article was published in the journal Lab on a Chip detailing a new method that allows scientists to image nanoscale biological structures in their native habitats for the first time.

Now, Demmert is working toward authoring his own journal article on writing a software program that automatically selects the best electron microscope tomography images to create a 3-D reconstruction. Writing a journal-quality research paper is a requirement for graduation. But even if it weren’t, Demmert would still be working toward that goal.

“I have an engineering background and I enjoy electron microscope tomography because it’s very physics oriented,” said Demmert. “What type of research I pursue after graduation depends on where I end up, but I know I’ll want to continue.”

The research portion of the new curriculum has been successful for these students and many of their peers, though several tweaks have been implemented for future classes. If these results are any indication, however, the program is on the right track.

“We want the first year to prepare students to begin their research projects immediately,” said LaConte. “And we want to provide them enough time to focus on all aspects of their education, including passing their boards and completing their rotations. We’re happy with the way things have gone so far, but we’re still zeroing in on the right balance.”

Friedlander, who also serves as the medical school’s senior dean for research, is convinced that the emphasis on research in the curriculum is well placed.

“Contributing to the training of scientist physicians by providing them with the tools and opportunities to conduct comprehensive, hypothesis-driven research under the guidance of accomplished investigators has been a key missing element of the health care training programs of many established medical schools,” he said. “We’re fortunate to have the intellectually curious motivated students who understand the importance of this as well as the visionary leadership of Virginia Tech and Carilion Clinic and the buy-in of our colleagues who contribute to this process. The medical school’s graduates will make a difference not only by the excellence of care they provide to their patients, but also by the help they provide to so many they’ll never meet by advancing the quality of health care through discovery and innovation.”

“No one knows where these students will take their expertise once they graduate,” said Dr. Cynda Johnson, dean of the medical school. “But whatever they choose to do, they’ll succeed. The quality of their work proves that. With the skills they’re building, they’ll be able to go out into the world not just as published scientists, but as better doctors. I can’t wait to see what they’ll achieve.”