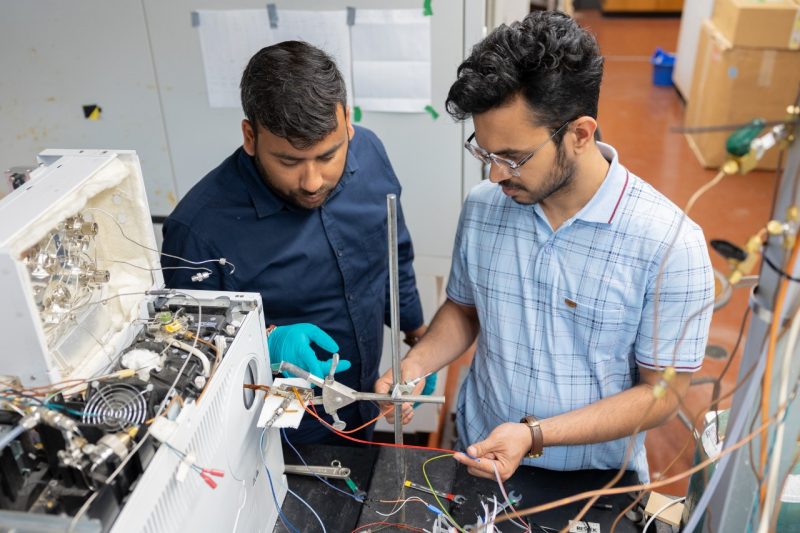

Unexpected impact: Ph.D. student Nipun Thamatam revamps a key part of microfluidic research

An ordinary day Thamatan's life led to a discovery that transformed decades of micro-electrical-mechanical systems research.

When Nipun Thamatam joined Masoud Agah’s micro-electrical-mechanical systems (MEMS) lab six years ago, he had no idea he would change the course of his advisor’s research.

Thamatam invented fluidic and electrical modular interfacing (FEMI) architecture, a patent-pending design for removable cartridges in gas chromatography. Unlike some micro gas chromatographs that use permanent glue for their core processing parts, FEMI makes it easier to remove faulty chips or wires with its building-block system.

“When I came up with the idea, it was just another day for me,” said Thamatam, an electrical engineering Ph.D. student in the Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering who will graduate in December. “It felt obvious to combine capillary tubing with the microfluidic chip, and honestly, I still find it hard to believe that it had such a big impact. Masoud and I actually argued with each other about it.”

FEMI has already been incorporated into other work in the lab, including Agah’s miniaturized gas chromatograph and the Personalized Integrated Mobile Exhalation Decoder, for which Agah, Mustahsin Chowdhury Ph.D. ’24, and Thamatam were recently awarded a patent. Their MEMS research opens up the world of individualized care with a focus on early diagnosis to reduce the burden on patients, doctors, and hospitals.

Meant to be a Hokie

Like many young engineers, Thamatam always wanted to build things. He enjoyed anything mechanical, especially technology that combined designing and fabrication. Growing up in India, he was drawn into engineering by the hands-on experience provided to him and his siblings by their father, a civil engineer.

“He’s very passionate about teaching us how things work without oversimplifying it,” he said. “When I was very young, he used to take us to construction sites and give us surveying tools to explore. He even spent three months of his salary just to get a computer with access to computer-aided design software for his work and taught me basic architectural design. And one of my fondest memories is building a metal barbecue with water flowing through it to generate steam.”

After completing his undergraduate degree at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science-Pilani (Goa Campus), Thamatam went to Arizona State University (ASU) to pursue a master’s degree, focusing on microfluidics, a subcategory of MEMS. After an unsuccessful round of Ph.D. applications, he found a posting for a research scientist position with Agah.

“I emailed him, saying I was interested in the position, but was honest that I wanted to do a Ph.D. later,” Thamatam said. “He asked, ‘Why not do it with me?’ I said yes, and when I spoke to my ASU advisor later, she told me that Agah had been doing microanalytical systems research for a long time. It was a very serendipitous accident to find the perfect Ph.D. advisor.”

Building a helpful future

Thamatam’s big picture dream is to continue his hands-on building and create something like the Personalized Integrated Mobile Exhalation Decoder for disease diagnosis that can be used in his home country of India. The seventh-largest country in the world, India is home to 1.4 billion people and features an incredibly diverse landscape, which can be difficult to navigate for appropriate medical care.

“Monitoring health in rural parts of India can be quite difficult,” he said. “I want to build something that can be deployed in a low-resource setting for early warning, if not for full diagnosis. I think MEMS and microfluidics have a very good potential to solve these kinds of issues.”

Regardless of what he ends up researching or building in the future, Thamatam is looking forward to the possibility of being closer to his partner of 13 years, Shailaja Akella, a computational neuroscientist at the Allen Institute in Seattle, Washington.

“Shailaja has been there for me in every aspect,” Thamatam said. “She kept encouraging me to find what I truly enjoy, whether it was my space research internship or my Ph.D. We’ve had to do long distance for years now, which is stressful, but she’s been very supportive throughout all this time.”

Related content

Mustahsin%20Chowdhury,%20Nipun%20Thamatam,%20Suman%20Dewanjee%20--%20Ben%20Murphy.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)