Teresa Southard seeks answers in veterinary forensics cases

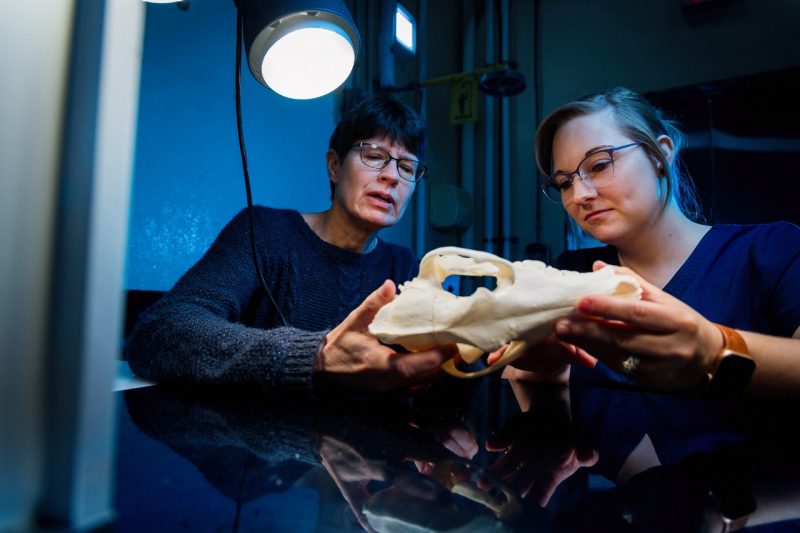

As a board-certified veterinary anatomic pathologist, Teresa Southard is no stranger to piecing together clues.

Pathology is the study of injuries and diseases, and anatomic pathologists perform necropsies and biopsies to uncover the disease processes at play and determine a cause of death or cause of illness.

Southard, associate professor of anatomic pathology at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, has a particular interest in forensic pathology, performing necropsies to uncover the truth behind animal deaths that may relate to illegal activity, such as neglect and abuse. Forensic pathologists are often called in to testify in court, working with the justice system to uncover the truth.

Working on cases of horrifying violence and neglect can take a huge emotional toll, but Southard finds strength in the fact that her work can prevent future suffering.

"There's a sense of satisfaction that you've contributed to the justice process,” Southard said. “Whether you find out that this animal died of natural causes and the person being blamed for it is innocent, or if you find out that someone intentionally hurt or neglected an animal and you can be part of the process that keeps them from doing that again, it’s rewarding.”

Since joining the college in 2021, she’s worked on over 70 forensic pathology cases in addition to her usual load of necropsies and biopsies.

Finding the answers

After a Ph.D. in biomedical sciences and an Air Force career, Southard entered veterinary school intending to become a veterinarian for lab animals, but after a pathology rotation, she was hooked. As Southard puts it, “Pathology is where you really find out the answers.”

During her anatomic pathology residency at Johns Hopkins University, Southard volunteered her necropsy skills at a Baltimore animal shelter.

"That’s where I started to see some of the evidence of neglect and abuse,” she said.

After taking a job at Cornell University, Southard built upon her forensic pathology experience as she worked alongside Sean McDonough, a trailblazer in the field. At Cornell, Southard performed over 500 forensic necropsies and appeared as an expert witness in nine criminal trials.

She joined the veterinary college at Virginia Tech in 2021 and quickly built a relationship with Baltimore City Animal Control, who now sends its forensic cases to her.

Because they are often asked to testify in court, forensic pathologists must go beyond the normal necropsy procedure.

"One of those extra duties is trying to figure out how long the animal has been dead in some cases, because that could help identify suspects,” Southard said. “We also have to document everything carefully, because if we have to go to court, it’s much easier to show a picture than describe what you saw, and it’s much more convincing to the jury. And lastly, we're asked to comment on the degree of suffering or pain an animal encountered, which is not a part of our normal necropsy procedure.”

Bridging the knowledge gap

"There's this thing called the CSI effect, where we expect to know everything within a nice, 45-minute segment, but it doesn't always work out that way,” Southard said. That goes double for veterinary forensic pathology, where in many cases, the information just isn’t out there.

With less research and less data, veterinary forensic pathology struggles behind human forensic science, but Southard and others are working to bridge that gap.

For example, Southard once tried to determine whether the pattern of fractured ribs in a dog was consistent with the history of a caretaker tripping and falling while carrying the dog. She pored over the published data, but there wasn’t enough information on the mechanisms behind different canine rib fractures to form a conclusion.

Instead, she took matters into her own hands. Using cadavers, she studied how different mechanisms of injury to the thorax form different fractures. With this new information, she determined that the dog’s injuries were consistent with the history.

Southard is currently finishing her master's degree in veterinary forensic sciences at the University of Florida, one of only two institutions in the United States that offer degrees in forensic science.

As part of her master’s thesis, Southard is collaborating with the Virginia Tech College of Engineering’s Busting lab to study the strength of bones using samples from canine cadavers. The lab offers mechanical tests that measure tensile strength, compression, hardness, and more.

"This kind of research is something that is lacking in the veterinary field,” Southard said. “We get asked these kinds of questions in trials — how much force does it take to break a dog's femur? We know a little bit from experience because we have seen fractures where we know the causes, but we need to be able to quantify these things.”

A small but mighty field

Although the number of trained veterinary pathologists has increased over the years, the number of pathologists with training and experience in forensic cases remains small. In the late 1990s, only one veterinary college in the country accepted forensic cases, and though that number has grown, there are few institutions where veterinarians can get forensic pathology experience. In the United States, the first textbook on the subject was published in 2006.

However, as the number of trained veterinary forensic pathologists has increased, so has the demand for their expertise. Over the past few decades, more and more research points toward a connection between violence against animals and violence against humans, and this has spurred law enforcement to take a deeper look at cases that involve animals.

At the veterinary college, Southard delivers lectures on forensic examination and on testifying as an expert witness. Veterinarians rarely have training in that area. There is currently no requirement for accredited veterinary colleges in the United States to address the topic, and a recent study showed that more than half of U.S. veterinary school do not address animal abuse in their core curriculum.

Southard described testifying in a case in which the animal’s primary veterinarian was also called in to testify, and the other veterinarian felt blindsided by the process and expectations. Southard wants the next generation of veterinarians to be better prepared and to be more aware of animal abuse and the responsibilities of veterinarians in abuse and neglect cases.

"My goal is that every student who graduates from this school — or any vet school — should be thinking about animal abuse, they should be aware of what some of the common signs are, and they should know what to do when they suspect abuse or neglect, at the very minimum.”

Through education, research, necropsies, and testimony, Southard works to expand the pool of knowledge so that justice can be served.