Fralin Biomedical Research Institute team unpacks genetic mysteries behind childhood epilepsies

Matthew Weston, associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, will lead efforts to understand how gene variants linked to severe, treatment-resistant childhood epilepsy disorders alter electrical activity in the brain.

Epilepsy is a brain disorder that causes recurring seizures.

It is one of the most common neurological diseases, and it affects approximately 50 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. In 2023, nearly 450,000 children in the United States were diagnosed with the disease.

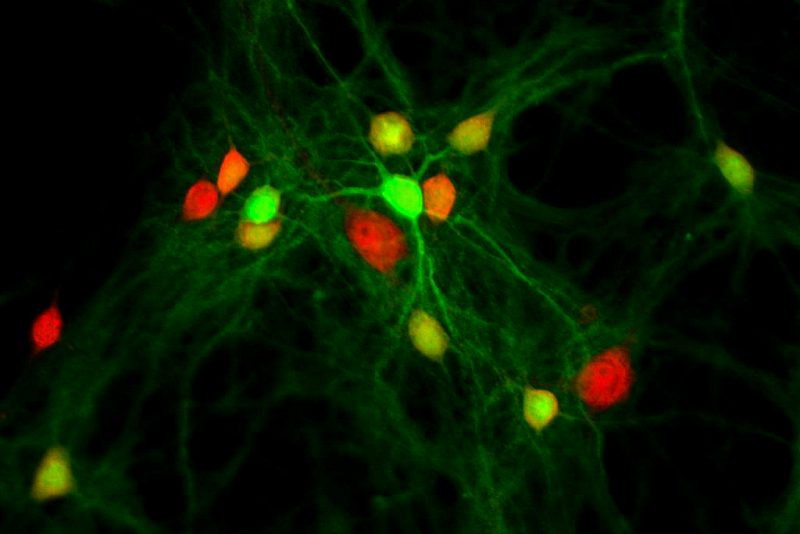

Researchers at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC are exploring how gene variants identified in children with severe epilepsy can have an impact on neurons, leading to abnormal electrical activity in the brain and recurrent seizures.

With two recently awarded grants totaling $2.4 million from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health, scientists led by Matthew Weston will use mouse models expressing these epilepsy-associated gene variants to understand how they alter neuron behavior to cause seizures.

The Weston lab is particularly interested in a gene called KCNT1. This specific segment of DNA carries the instructions for a protein that forms an ion channel that acts like a tiny gate embedded in the membrane of neurons to control the flow of potassium ions.

This flow is essential to help neurons communicate properly and regulate the electrical activity in our brain, according to Weston, associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.

Changes in this gene affect normal nervous system function and can lead to seizures by causing a dysregulation of electrical stabilization in neurons that can spread across networks throughout regions of the brain. Earlier investigations by Weston’s team examined the influence of KCNT1 genetic abnormalities on the excitability of neurons, indicating their potential connection to epilepsy.

"We’re using mouse models with the exact same KCNT1 mutations that cause severe and untreatable epilepsy in kids,” said Weston, who is also an associate professor in Virginia Tech’s School of Neuroscience in the College of Science. “By closely examining these models, we hope to discover a path to therapeutic intervention.”

Weston is collaborating with Wayne Frankel, professor of Genetics and Development at Columbia University’s Institute for Genomic Medicine. Frankel recently designed new research models for this study: a model with the KCNT1 genetic mutation in all neurons and another model that allows the KCNT1 genetic mutation to be expressed only in a subpopulation of neurons to identify which neuron types are most important for the disease.

By looking at the neurons in the brains of these models, Weston aims to uncover fresh perspectives on the alterations in neuronal function induced by KCNT1 mutations, resulting in heightened excitability and seizure occurrence. More importantly, he hopes to pinpoint the neuron types most susceptible to these changes, potentially guiding the development of innovative treatment strategies.

“With these models, we’re hoping to find new mechanisms underlying the disease and point to new therapies,” Weston said.

Weston serves on the scientific advisory board for the KCNT1 Epilepsy Foundation, which supports research and drug development with the ultimate goal of finding an eventual cure for KCNT1-related epilepsies.

Amy Shore, a research scientist in Weston’s lab, finds inspiration in the connection with the foundation.

“Engaging with parents, and hearing stories about the devastation of this disease on their children and their daily lives, motivates us to focus and do our best to find answers that can translate into hope,” she said.