Pilot program aims to draw more Black students to teaching careers

Data shows public school teachers in America are much less diverse than their students.

Add the nationwide teacher shortage and finding and retaining educators from traditionally underrepresented groups becomes a daunting task – especially in the STEM fields.

While the number of Black, Hispanic, and Asian American teachers has increased in recent decades, it hasn’t kept pace with the growth of students from those same populations, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Numbers from the Pew Research Center show that for the 2017-18 school year, Black educators made up 7 percent of the workforce compared to Black students, who were 15 percent of students in U.S. public schools.

A hands-on approach to addressing a critical need

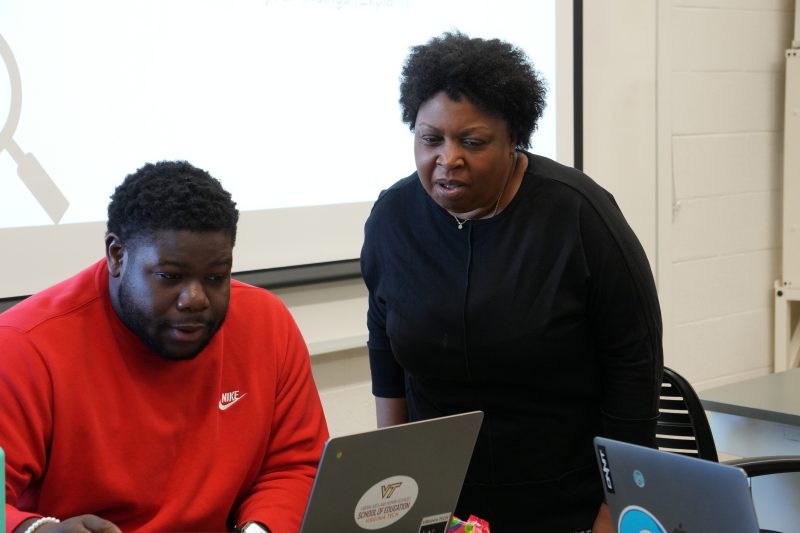

That critical shortage is exactly what Brenda Brand and Lezly Taylor set out to address when they developed a partnership for graduate students between Virginia Tech and Shaw University, a historically Black college or university (HBCU) in Raleigh, North Carolina. Brand is a professor and program leader at Virginia Tech for the School of Education’s science education and STEM education programs, and Taylor is an assistant professor in the science education program.

The partnership, which is in its pilot year, would act as a pipeline to Virginia Tech for students who have already graduated from a historically Black college or university with a STEM-related bachelor's degree. As Hokies, these students would pursue a graduate degree in teaching.

“There are not enough teachers who look like minoritized students in the classroom,” said Brand. “This initiative grew out of a need for us to increase the numbers of teachers going into STEM, but also to help increase students going into STEM teaching from historically underrepresented groups.”

Taylor said that it is important to remember that the lack of diversity within the teaching profession is structured by historical and systemic inequities that have persisted over time and in turn have contributed to the underrepresentation of minorities in teaching.

“Addressing systemic challenges requires an informed approach that deals with barriers to the teaching profession as it relates to recruitment, preparation, and retention,” said Taylor. “This partnership aims to contribute to reducing disparities in the teaching profession, ensuring that every educator can deliver a quality education and that every student can access it without barriers.”

Through a mutual colleague, Brand contacted Kimberly Raiford, who is the department head for health, human, and life sciences at Shaw University. Raiford said the idea for the partnership felt like the perfect fit because her department was already working on finding different avenues for the university's science majors.

“So many people from traditionally underrepresented groups are never even presented the possibility of teaching, but once they find it, they bring so much life, energy, talent, and love into the classroom,” said Gerard Lawson, interim director for the School of Education.

Applications for the partnership went out, and two Shaw students, Javari Burgess and Whitney Osideko, were accepted to be a part of the pilot year. Both students had worked with Raiford during their time at Shaw and possessed what she described as an “it factor.”

“Javari worked in the lab with me and was training other students, and so I saw this knack for teaching in him that he hadn’t fully come to understand,” said Raiford. “It was the same thing for Whitney. She just had that ‘something.’”

Neither student had thought about pursuing education as a career before the partnership. Both were considering careers in medicine or coaching.

“Now these students have become ambassadors for teaching as a career," Lawson said. "Now they are the ones showing their students that there are plenty of opportunities to take the skills they have, whether that is in science, math, history, or music, to help teach the next generation of students.”

Growth in the classroom and beyond

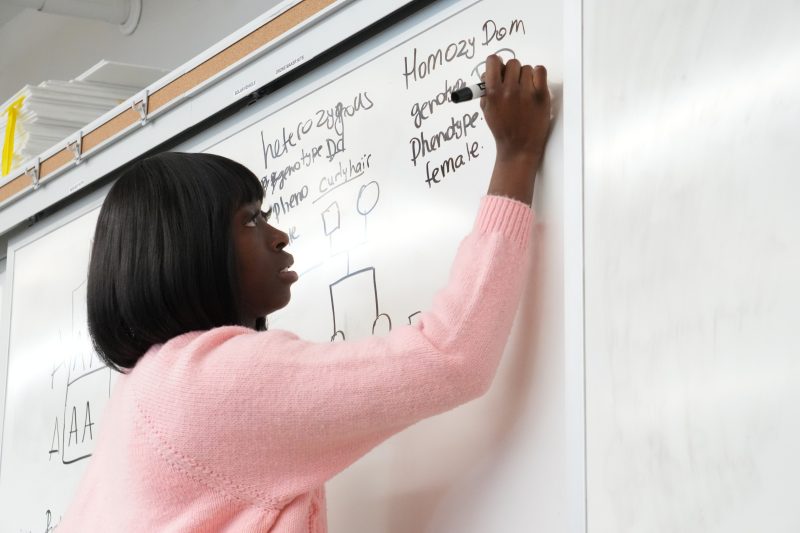

Both Burgess and Osideko were student teachers at Christiansburg Middle School last semester, which has a Black student population of 7 percent, according to the Virginia Department of Education. They both said that opportunity gave them a perspective into what public school teachers from marginalized backgrounds are experiencing.

“It meant a lot to me because a lot of students don’t look like me and there are kids that, in order for them to understand, they have to have some type of correlation with someone else,” said Javari. “Looking like a kid as far as race, that’s big. It’s big, really big – it’s important to the student and the teacher.”

Osideko said she had a similar experience and hopes being in the classroom and interacting with students helped dispel common stereotypes assigned to Black women.

“I wanted my presence there to be a cultural enrichment for my students,” said Osideko. “I just made sure that my presence was like, ‘OK, this is another chapter that you can add to your book on how to approach Black people and Black women in general.’”

The positive impact of this partnership doesn’t stop with Burgess and Osideko. Taylor said that it’s expanded her understanding of the barriers that impact a diverse teaching profession as well as enriching classrooms within the science education program and beyond.

“The perspectives on education have been profound as the classroom is filled with students from varying backgrounds and experiences. I have enjoyed seeing the students create their own community within the classroom and I have immensely enjoyed observing their support of each other academically, emotionally, socially, and professionally,” said Taylor. “The teachers and the students that have hosted the HBCU students have continuously communicated with me how much these students have been a gift to their classrooms. I personally think we need more of that.”

Since coming to campus, both students have embraced Virginia Tech and the Ut Prosim (That I May Serve) lifestyle.

“At Virginia Tech, it feels like you always have people in your corner that are willing to help, willing to look out for you,” said Burgess. “It made me want to go into teaching more because if you show a student that you care, they will be the best student. They’ll do whatever it takes because they see that someone is caring for them.”

Osideko said she wants other students to know such partnerships may seem daunting, but are worth the leap of faith.

“You kind of have to force yourself into situations when you want to succeed, because I have found myself being the only Black girl in more situations than I can count,” said Osideko. “And I appreciate it, because it gives me an opportunity to expose myself to others and to have them exposed to me. I want there to be a positive carryover when they interact with me.”

What’s next?

Once he graduates, Burgess said he hopes to become a teacher in Atlanta – his home city. Osideko said she is still undecided, but that she will either go into teaching, return to the healthcare field, get another degree, or move into the tech field.

Brand and Taylor are looking into funding options to sustain the partnership and its mission, as well as continue to combat negative stereotypes surrounding the teaching profession.

“If we’re able to sustain it, I think this partnership has the potential to make our program a premier program in the state and be a model for other programs,” said Brand.