International work puts robot avatars on the move

Graduate student Connor Herron went from Blacksburg to Genoa, Italy, to lend a hand in making a better system for long-range, remotely controlled robots that walk on two legs.

The term “avatar” might be most familiar as a picture used on social media, but in the technology world, it can mean much more.

When James Cameron’s hit movie "Avatar" came to theaters in 2009, it introduced a concept already cooking in the technology community: for a connected operator to be able to fully remotely opperate the movements of a robot. In the movie, the robots were biological, but the technology in the real world is connected to more traditional robots with circuits and computers. These also are called avatars.

Electronic avatars have many of the same features as the movie: A person gears up from top to bottom to control various movements of a robot. There is a headset that connects the person to the robot’s vision, a glove-like mechanism that enables gripping and movement of the robot’s hands, and a way to track the motion of feet to make the robot walk.

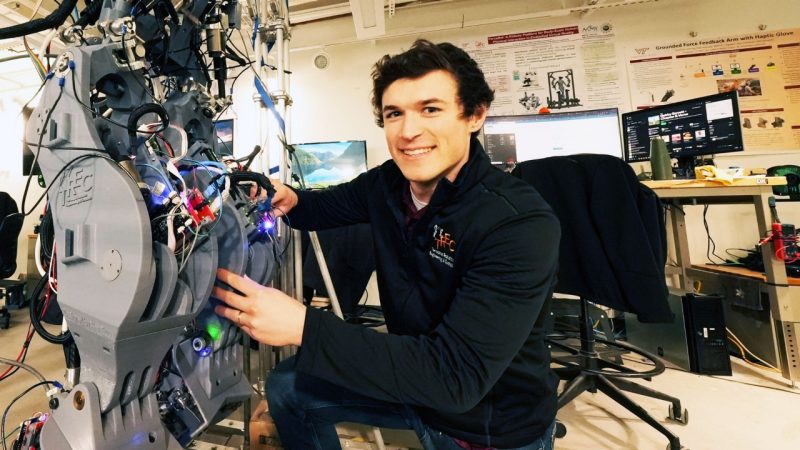

Virginia Tech has several projects connected to this type of work, many of which have come from the Terrestrial Robotics Engineering and Controls (TREC) Lab within the Department of Mechanical Engineering. Connor Herron is a Ph.D. student who has been central to the lab’s work since joining the team in 2017 as an undergraduate researcher, and now has helped a robotics team in Italy help get their avatar moving.

Coming in at the end

The Artificial and Mechanical Intelligence (AMI) Lab based in Genoa, Italy, within the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, was reaching the end of a four-year project using an iCub humanoid robot to deploy a fully functional avatar for an international competition. The team's objective was a strong showing for the All Nippon Airways Avatar XPrize, and its members wanted to do something that was especially challenging: make an avatar that walked on two legs.

This was ambitious. According to the group’s publication in Science Robotics, a two-legged design can perform more complex movements in reduced and confined spaces, but making the avatar stable enough to remain upright while walking is a challenge.

This was the area where Herron was needed. His work in the TREC lab included several projects that deployed two-legged robots, and he had extensive experience working with robotics that were connected via virtual reality and other remote controls.

Daniele Pucci, the lead researcher at the lab in Italy, said Herron brought value to the lab.

“Connor was given the challenging task of teleoperating the robot walking using shoes,” Pucci said. “We had just a vague idea on how to do this, and the tough job was indeed the implementation and testing of this idea.”

New shoes

Herron entered the project in the final three months before the competition. He was brought to Italy on an internship through the National Science Foundation as the AMI team was moving away from an approach that used a swiveling platform on which a user would walk, sending movement commands much like a joystick might to move the avatar. During testing, this mechanism had proved to be less than optimal, and the team wanted to make the movement of users easier during the connected experience.

Herron picked up the project as the team was shifting to designing a shoe equipped with pressure plates to detect the force exerted while walking and motion detectors that tracked the position of each foot. This would provide the same control over the remote robot, but was much easier to set up and use.

“It took about four hours to set up the old system for walking,” Herron said. “With this new system, it took about 10 minutes.”

At the international competition, the user was located about 300km from the avatar, which was on the competition stage. The team was a finalist in the competition.

“Developing humanoid robots is still challenging and takes a monumental amount of effort to realize simple balancing tasks like walking or lifting objects that most people complete effortlessly,” Herron said. “While robust balance is still important, the research and industry are at a point where we are focused on defining how humans and robots can safely collaborate to improve our everyday lives.”