What if cows could talk?

By using acoustic data and machine learning to decipher cows' vocalizations, Virginia Tech researchers hope to shed new light on the animals' health, welfare, and environmental impact.

You may not know it, but cows share information every time they burp, moo, and chew that speaks volumes about their health and welfare.

Through the work of researchers in Virginia Tech’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, we may soon know more about what cows are “telling” us and be able to use that information to improve their well-being.

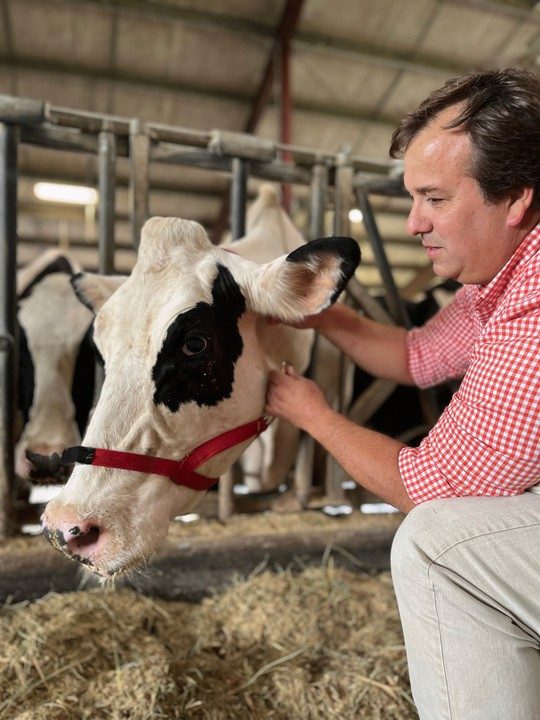

James Chen, an animal data sciences researcher and assistant professor in the School of Animal Sciences is using a $650,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture to develop an acoustic, data-driven tool to help enhance animal welfare and lower methane emissions in precision livestock farming.

“Vocalization is a major way cows express their emotions, and it is about time to listen to what they’re telling us,” Chen said.

Because sound data can be collected from cows individually and continuously, Chen said it’s better than video or other observation methods for monitoring cows’ emotions and health, including even subtle changes in breathing.

“The assessment of animal welfare has become a central discussion in society and is a controversial issue simply because the lack of objective tools leads to biased interpretations,” he said. “By matching audio data with biological and visual cues, we can be more objective in our approach to analyzing their behavior.”

Using artificial intelligence to interpret moos

Chen and his co-investigator, Virginia Cooperative Extension dairy scientist and Associate Professor Gonzalo Ferreira, plan to collect audio data from cows, their calves, and beef cattle in the pasture. They will then use machine learning to analyze and catalog thousands of points of acoustic data and interpret cow vocalizations such as mooing, chewing, and burping for signs of stress or illness.

“Let’s think about a baby crying inside a plane or in church,” Ferreira said. “As a father, I have an idea whether the baby is crying because it’s hungry or wants attention. Our research question then is: Can we use audio data to interpret animals’ needs?”

Chen and Ferreira are particularly interested in identifying vocal patterns for how cows’ communicate distress. By analyzing the frequency, amplitude, and duration of cow’s moos and vocalizations and correlating the sound data with saliva cortisol samples taken from the cow, they can classify whether cows are experiencing no stress, mild stress, or severe stress and begin to decode their “language.”

As part of the project, Chen is building a computational pipeline that integrates acoustic data management, pre-trained machine-learning models, and interactive visualization of animal sounds. The resulting data will be shared in an open-source, web-based application available to scientists, producers, and the public. Chen said his hope is that the information will help guide future protocols to improve animal welfare.

“Anyone can directly plug in and use our model to run their own experiment,” he said. “This allows people to transform cows’ vocalizations into interpretable information that humans can recognize.”

Decoding burps

Because cows’ burps can release small amounts of methane, the researchers also will try to identify cows that burp less through audio data. By comparing the sound data to DNA samples from the cows, they hope to understand whether a genetic variant causes some cows to burp more than others. They also plan to examine the impact of rumen modifiers — food additives that inhibit methane gas production — to gauge the effects.

“Measuring methane emissions from cattle requires very expensive equipment, which would be prohibitive to farmers,” Ferreira said. “If burping sounds are indeed related to methane emissions, then we might have the potential for selecting low methane-emitting animals at the commercial farm level in an affordable manner.”

“Our eventual goal is to use this model on a larger scale,” Chen said. “We hope to build a public data set that can help inform policy and regulations.”

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)