Common challenge, different strategies: Virginia Tech Cancer Research Alliance gathers broad mix of researchers and clinicians

The second annual Virginia Tech Cancer Research Alliance retreat, hosted this year on the Children’s National Research & Innovation Campus, brought together scientists and physicians on the leading edge of developing innovative therapy types, fresh biological targets, and new technologies to take on cancer.

In a time when 2 million people in the United States alone are projected to be diagnosed with cancer this year, and 600,000 will die, Virginia Tech and other scientists came together to explore new ways to combat the deadly disease.

Investigators from Virginia Tech, its research and clinical partner Children’s National Hospital, and other institutions gathered on the Children’s National Research & Innovation Campus in Washington, D.C., in May for the second annual retreat of the Virginia Tech Cancer Research Alliance.

Seven speakers, a mix of scientists and physicians conducting clinical trials, described innovative therapy types, fresh biological targets, and new technologies in the hopes of fostering collaborations between scientists and institutions.

“We were fortunate to have speakers working on cancer who are physicians, physician scientists, engineers, behavioral scientists, and veterinarians carrying out leading edge research to benefit adults, children, and pets,” said Michael Friedlander, executive director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, Virginia Tech’s vice president for health sciences and technology, and founder of the Cancer Research Alliance. “This type of interdisciplinary collaborative science that eschews administrative and disciplinary boundaries is at the heart of what Virginia Tech is about.”

Keynote speaker Jay Berzofsky, chief of the vaccine branch at the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute and a pioneer of cancer vaccines, described advances in his field.

Unlike most vaccines, which are designed to prevent disease, a cancer vaccine would also be a treatment that aids the body’s natural ability to fight cancer by inducing an immune response.

“I think it's a much more promising time for vaccines, much more hopeful that now, in combination with these other immunotherapy mechanisms, that vaccines will work,” Berzofsky said.

Catherine Bollard, director of the Center for Cancer and Immunology Research at the Children’s National Research Institute, outlined innovative approaches in immunotherapy for solid tumors in pediatric patients – a particularly tough cancer.

“We need the critical partnerships that we have with basic scientists and cancer biologists and all the groups and all the stakeholders,” Bollard said. “The only way to affect a cure is to bring us all together and to combine our targeted therapies with our complex biologics and hopefully really get to that stage for all our patients.”

Eugene Hwang, principal investigator of the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium at Children's National Hospital who conducts clinical trials, stressed that the collaborations between lab scientists and physicians are especially crucial.

“Not only do you need lateral linkage so that everybody who's working on this is talking and collaborating and working together, you actually need some verticality,” he said, so that information and understanding can be shared up and down the research pathway from laboratory to clinic and back.

New targets, new technologies

“It’s very clear that the interdisciplinary research we are doing on both campuses is paying off for patients,” said Carla Finkielstein, professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, co-director of the research alliance, and co-chair of the retreat with Associate Professor Samy Lamouille. “I think the work we've done back in Roanoke, the work done here, complements very well. It's a synergistic opportunity for all our researchers and it has been demonstrated today in all the presentations.”

Finkielstein’s presentation about the role of the circadian clock in the growth and spread of cancer was just one of example of the innovative approaches to understanding cancer showcased at the retreat.

Kathleen Mulvaney, assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute who conducts research at the Children’s National Research & Innovation Campus, hopes to develop a drug that targets a particular enzyme that’s crucial to the growth and survival of devastating pediatric brain tumors.

On the technology front, two Virginia Tech researchers described their use of focused ultrasound in a developing therapy called histotripsy.

Eli Vlaisavljevich, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics, and Joanne Tuohy, assistant professor in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine’s Animal Cancer Care and Research Center, are both exploring using the method to ablate cancer tissue noninvasively by using focused ultrasound to generate, grow, and collapse cavities in the tumors.

Tuohy, a veterinarian, also represented the nexus of animal and human cancer research and how scientist on those areas can collaborate and learn from each other.

“I feel so fortunate I was invited to give that talk and to kind of let people know what we are doing with our canine and our feline pet models and how we can help contribute to cancer research and help make it better for people as well,” she said.

Common problems, different perspectives

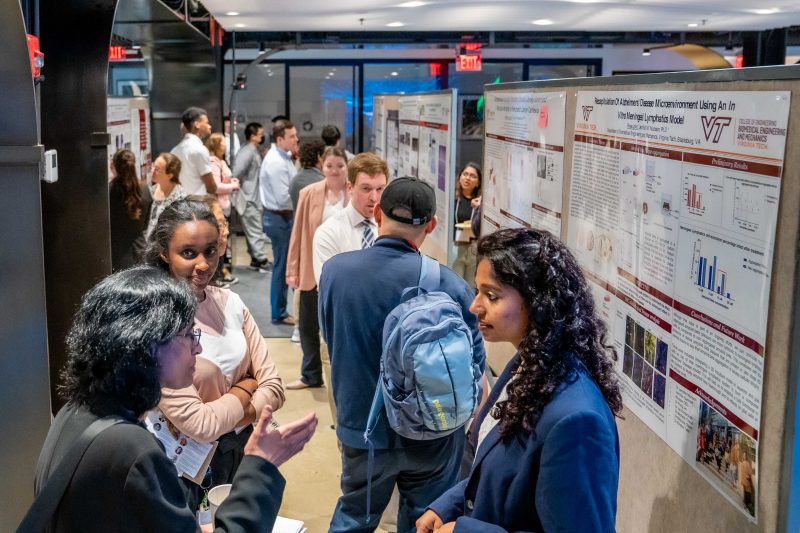

Many graduate and medical students, including from Virginia Tech’s Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health program, presented their own research during a lunchtime poster session, where they took questions and heard feedback from leading-edge researchers.

“Every one of our students has had a big smile on their face because they're so excited to see how all of this work comes together to give them a glimpse of the future in cancer therapeutics,” said Lee Learman, dean of the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine.

The buzz and excitement created by conversations and shared research during the retreat were palpable.

“You can feel it,” Friedlander said. “It just adds a whole other dimension to the intersectionality, the approaches to common problems with different perspectives, and is exactly what is needed in the field of cancer, and this meeting embodies that.”