A balancing act: Engineers combine wearable sensors and training to help reduce trip-induced falls

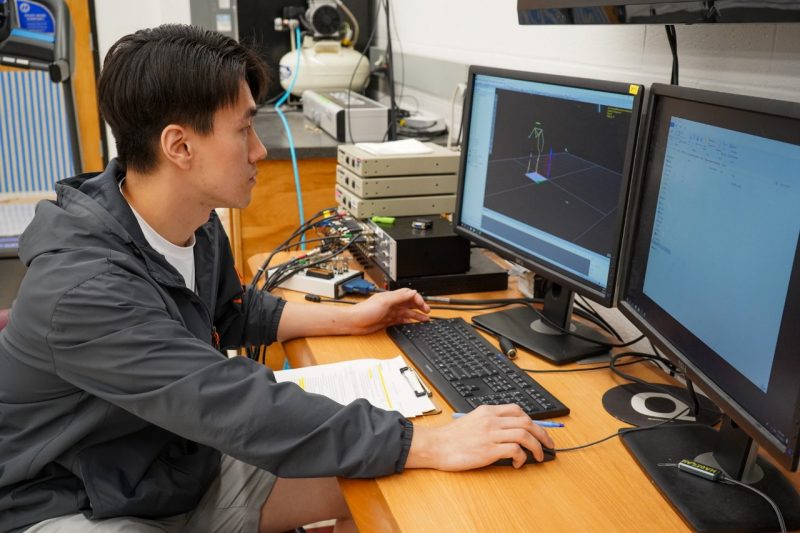

Professor Michael Madigan and Ph.D. candidate Youngjae Lee with the Grado Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering are seeking cost-effective and accessible solutions to a common problem: trip-induced falls.

The sounds of Jon Passic’s footsteps inside the Occupational Ergonomics and Biomechanics Lab in Whittemore Hall were barely discernible over Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets” blaring from a small speaker.

Passic, who wore a fall protection harness connected to an overhead support system, paced back and forth on the lab’s testing walkway. Suddenly, the whirring of the harness stopped as Passic tripped over a manufactured hazard in his path. He reacted with a series of quick, short steps, pulled his body upright, and continued to walk forward as a group of graduate students and researchers watched his every move on a set of monitors.

While the trip was unexpected for Passic, the team of engineers conducting this experiment had meticulously planned that exact moment to observe his recovery.

Passic is just one participant in a study led by the Madigan Biomechanics Group in the Grado Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering that seeks solutions to a common problem: trips and falls. Professor Michael Madigan and Ph.D. candidate Youngjae Lee are researching how an innovative balance training regimen could potentially reduce injuries sustained from trip-induced falls in adults over 65.

“Falls are the No. 1 contributor to injuries among adults over the age of 65, and tripping while walking is a major reason for this,” said Madigan. “How we move our body in response to a trip makes all the difference in the world in terms of whether we will fall or be able to recover our balance. What we’re doing with this training is trying to improve that response, so we can do it effectively without thinking about it."

Modern, accessible solutions for a common problem

Improving a person’s balance to prevent serious falls is not uncommon research for human factors groups, but balancing efficacy and accessibility can be challenging. For Madigan, however, this is not his first venture to harness an innovative solution to preventing trip-induced falls. His prior research focused on understanding why falls happen and developing corresponding balance training programs to improve reactive response after a trip. Most of this training used a highly specialized treadmill, which while effective, proved to be expensive and cumbersome.

“Even if the treadmill works from a scientific perspective, we had to consider if it was cost effective for the end user,” Madigan said. “That’s really most of our focus for this research — how can we get rid of the treadmill all together while still training better responses to a trip?”

Removing the treadmill not only makes the training much more cost effective, but also increases accessibility. Training could then take place at senior community centers, rehabilitation offices, retirement communities, and other locations.

“Dr. Madigan mentioned that non-treadmill training could hopefully resolve limitations regarding cost and space,” Lee said. “It was a perfect fit for my research interests. We went through multiple pilot studies to develop a non-treadmill training method, and the current protocol we’re using is a result of those studies.”

After the pilot studies were completed, Lee sorted his research into three parts. First, Lee and Madigan developed a training program that focuses on reactively regaining balance after tripping. Next, Lee has been testing wearable sensors outside the lab to determine if they can accurately track movements and record data for researchers. From there, the goal is for the wearable sensors to measure the effectiveness of balance training in the real world — where trips are largely unavoidable and unexpected rather than a lab setting where most of this research has already been done.

Practice makes perfect

Lee’s research focuses on reactive balance, or a person’s ability to respond to a trip and regain balance, and researchers have identified key movements that can make this possible. Lee’s balance training helps participants regain their centers of gravity and strengthen their bodies so recovery after a fall is easier.

Prior research has shown that when people trip, they must do three things to prevent a fall:

- Quickly control the motion of their torso and try to avoid leaning forward.

- Take quick steps to get their feet in front of the center of their body and continue stepping forward.

- Ensure their legs don't collapse by maintaining adequate hip height.

The balance training allows participants to safely and repeatedly practice these movements in a controlled manner. Over the course of three weeks, Lee and other graduate students meet with participants twice per week to go through progressive stepping exercises that mimic the movements necessary to regain footing during a fall. Once participants are comfortable stepping, the training extends to balancing the upper body and learning to balance the torso.

At the end of their training program, participants harness up and test their balance recovery skills in the lab.

“Youngjae’s research is allowing people to practice these movements over and over in a safe, controlled environment,” Madigan said. “We’re able to put people in body postures similar to what they would experience if they tripped and then allow them to practice these critical movements that we, and others, have identified as the movements you need to complete to recover your balance. As much as we can, we try to simulate a real trip and let participants practice how they would respond to it.”

In addition to the balance training, participants wear the sensors that record body movements on their shoes and underneath their clothing outside the lab for three weeks after training. Lee checks the wearable sensors weekly to ensure they’re working properly and collecting data. Participants also use voice recorders to describe any incidents of trips and falls and subsequent response.

“The data from the wearable sensors shows us if there are any differences in responses to slips and trips from people who have completed the training,” Lee said. “Not only could these sensors provide meaningful data, they are also less expensive and require less setup time than similar testing in a lab.”

Lee plans to conclude research this summer and defend his dissertation at the end of the year. Pending results, researchers hope to partner with organizations and recruit even more participants to continue learning about mitigating trip-induced falls. Eventually, the goal is for balance training to occur in spaces widely used by older adults, such as retirement communities and senior centers.

To recruit participants for the study, Lee and Madigan partnered with Virginia Tech Center for Gerontology, the Virginia Tech Lifelong Learning Institute, local senior centers in Christiansburg and Blacksburg, and Warm Hearth Village.