Experiential learning model for engineering students evolves

A large group of engineering students spent much of the spring working with people in Virginia Tech’s Division of Campus Planning, Infrastructure, and Facilities on various campus projects, gaining real-world experience normally exclusive to juniors and seniors

Moments after listening to Jennifer Benning offer students in her Foundations of Engineering course the opportunity to work on campus projects with some of the university’s engineers, Catherine Shewchuk felt some trepidation about participating.

The Blacksburg High School graduate, now a rising sophomore at Virginia Tech, enjoyed the classroom setting and wasn’t quite sure about joining a real-world exercise normally exclusive to juniors and seniors.

But Shewchuk took the plunge, coalescing with a group that examined a stormwater management issue on campus.

“This project was good for me to get out of my comfort zone and try something a little more hands-on,” Shewchuk said. “We didn’t have any time to do any of the hands-on solution implementation … but we did get to do a site visit. Getting to do that was fun. I enjoyed that.”

Those were the reactions that Benning, an instructor in the Department of Engineering Education, and Matthew James, an associate professor of practice in the Department of Engineering Education, wanted as they offered first-year and certain second-year students this past academic year the experiential learning opportunities associated with Virginia Tech.

A unique partnership

Benning’s course is the second of a two-semester series for first-year students in the College of Engineering that serves as an introduction into the world of engineering. With a background in service learning, internships, and community partnerships from previous stops and through her involvement with Virginia Tech’s Climate Action Commitment, she became the leader of a pilot project that not only introduced first-year students to those in the Division of Campus Planning, Infrastructure, and Facilities, but also allowed them to work on certain projects for invaluable hands-on experience.

After applying for and receiving a VT Engage Faculty Fellows grant — which provides the financial resources for professors to integrate community-based learning experiences in their academic courses and programs — Benning developed a curriculum and on-campus partnerships that allowed all her students to participate.

“It was really my passion and my love of just getting students out doing real projects,” Benning said. “The first-year engineering program is a two-semester sequence, and so the first semester has more to do with learning about engineering. The second semester class is more of a semester-long engineering design project. I thought it would be nice if students were able to choose a project.

“There's a small fraction of them that felt a big project would be too much. They would say, ‘A smaller scale project that we could solve in a semester would be better,’ and Matt and I can understand that because I think, for some students, they just feel overwhelmed. But I think for most, this experience was overwhelmingly positive. They were excited about getting to do projects that are on campus. They felt real. They felt like they were a part of it.”

James teaches Engineering Education 3974, or Engineering Design for Community Impact. Students can take this course after completing their first-year engineering courses to continue to work on community-focused projects appropriate to their academic level. This course serves as a bridge between first-year engineering courses and higher-level design courses that students typically take in their junior or senior years.

James also possesses a background in experiential learning. His students have partnered with Friends of the Huckleberry Trail, a nonprofit group dedicated to building out and preserving the popular local multipurpose path, and Montgomery Museum of Art and History, which preserves local art. Departmental conversations led to him teaming with Benning and offering his students opportunities to work with those in facilities as well.

“When I polled the students at the end of last spring, I asked the question, ‘Would it feel like an external stakeholder if you all worked with one of the Virginia Tech units that's not an academic unit?’” James said. “And they said, ‘Yeah.’ They felt that working with dining or facilities or housing was just as much of an external piece because they don't really have that day-to-day interaction with those people quite as much as maybe you or I do.

“Jennifer had been having conversations with facilities, and I got looped in. We were able to put a comprehensive plan in place, and I think it’s been one that has worked out well for everyone.”

Projects and potential solutions

Over the winter semester break, Benning and James sat down with Matt Stolte, the university’s director of engineering services within the Division of Campus Planning, Infrastructure, and Facilities, who put together a team of engineers representing different areas of expertise. Both sides talked about needs and interests and came up with a list of projects for student involvement.

“We were interested in organizing it just to align with the mission of the university,” Stolte said. “We’re all here working for the university, and part of that is education. We were willing to be an introduction to engineering education and trying to have students participate in the day-to-day activities that we do on a regular basis just to show them what the career looks like.”

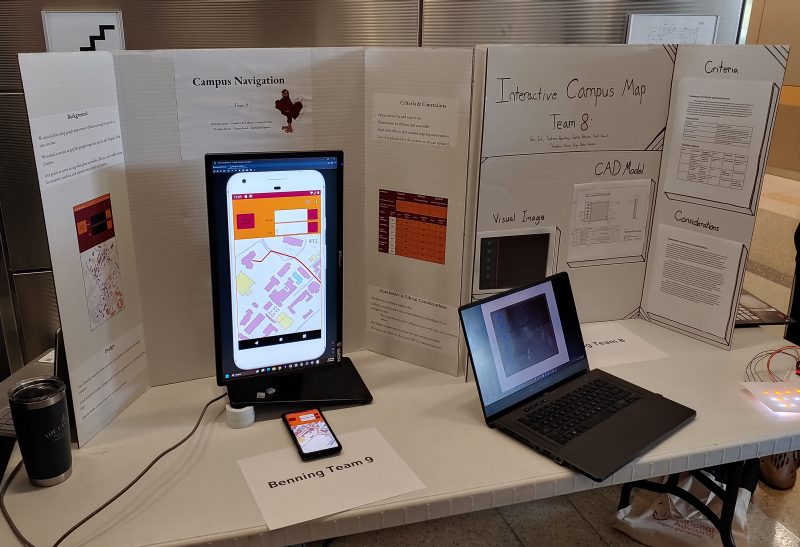

Some of the projects included a stormwater drainage problem next to a garage at The Grove, where Virginia Tech President Tim Sands and Laura Sands reside; issues with antenna systems and radios for fire and rescue personnel inside certain campus buildings; problems related to lab and office numbers in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine complex that wreak havoc on fire alarm systems; an analysis of retrofitting parking lot lights to LED for energy savings; and finding solutions for navigational issues on campus related to ongoing construction.

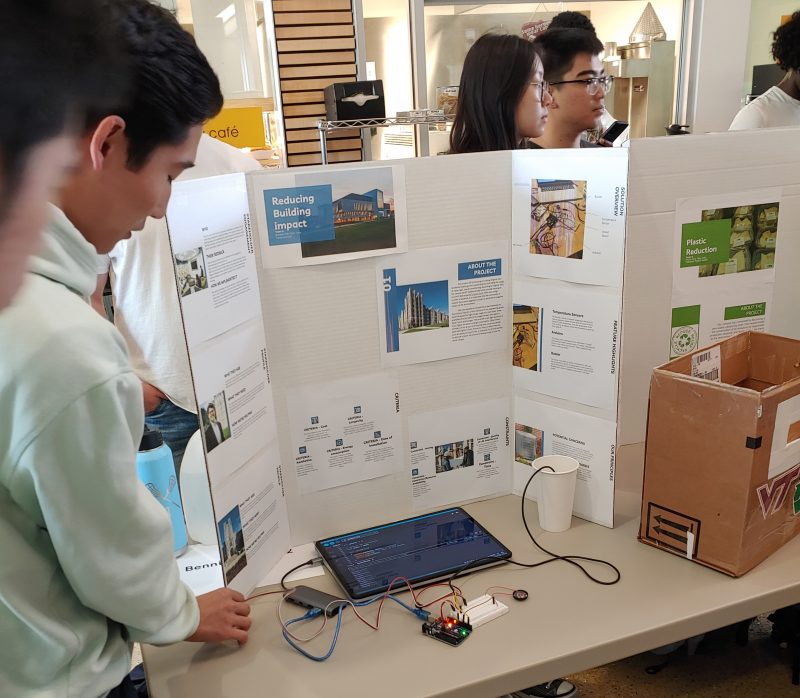

Groups of six students worked on each of these projects, with multiple groups working on the same projects. Baibhav Nepal, now a sophomore from Nepal, was on one of several teams working on the room numbering issues in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine complex, with its multiple buildings connected in a somewhat complicated floor plan.

This problem appealed to Nepal because of his love of computer science and computer engineering. He and his teammates soon realized that renumbering the rooms was an expensive solution, both in terms of labor and additional signage costs and reconfiguring fire, heating, and cooling systems. But Nepal and his group came up with navigational program for one of the floors that potentially could serve as a prototype for the others.

“It's been amazing to be a part of a project like this to be honest,” Nepal said. “We’re helping and suggesting design solutions to the team that is really working on the project. We’re not sure if our solution will be implemented or not, but at least we put a foot forward to that aspect. It’s been great.”

Shewchuk’s team analyzed the stormwater issue at The Grove. Like Nepal, she chose this project because of a personal interest. She eventually wants to get into urban planning, and managing stormwater runoff is prerequisite for city planners.

Stormwater off a garage at The Grove runs into Stroubles Creek, which flows to the New River. It potentially carries pollutants that could damage the New River ecosystem, so Shewchuk’s group came up with the idea of installing a bioretention area, or a collection of plants, that filter the pollutants and clean the water supply. Those plants also slow the rate of water flow, mitigating flooding and erosion issues.

“I especially wanted to look at this project because stormwater is very much a civil engineering problem,” Shewchuk said. “I wanted to get into something more hands-on and interact with people who do this sort of thing in their jobs, like the facilities department. Stormwater, being a civil problem, and me wanting to go into civil engineering, I thought it was the best match for me.”

An experiential learning model for all

The goals for the students weren’t necessarily to come up with solutions for issues, but to get them thinking about ideas and working together as a group. The projects forced them to think about multiple facets of an issue, which is important. In engineering, potential solutions often can have unexpected residual effects.

“It was interesting watching them fall into a bunch of rabbit holes as they started to explore one thing and then realize how deep each issue can go,” said Paul Ely, associate director of capital construction renovations and involved with navigational issues on campus related to ongoing construction. “But I thought the students were good. The projects they’ve been working on are more on the ground level — they haven’t been looking at huge things like how to retrofit the steam plant. They’ve all been looking at more practical things that people see all the time, and they usually have some neat technological solutions.”

Mark Webb, an elevator fire protection manager in infrastructure engineering operations who was looking into the issues with antenna systems and radios for fire and rescue personnel on certain campus buildings, agreed.

“We were trying to figure out how to re-test the antennas, and the solution one group came up with was basically amplifying the radios, so they’ll work,” Webb said. “We hadn’t thought of that side of it, and it’s actually more cost effective. I was very impressed with their view of that. Sometimes, they come in with a different perspective, and they showed that and had a solution.”

Those who work in the Division of Campus Planning, Infrastructure, and Facilities will spend the next several weeks and perhaps even months looking into the potential solutions proposed by the students. Not all ideas will work. Some just create additional problems, and others won’t be cost effective. Yet others may spark additional ideas that lead to solutions.

Both the students and university engineers benefitted from this partnership, and both hope it continues. Virginia Tech’s engineering students got exposed to the day-to-day responsibilities of various engineers and were part of a program that could be replicated by any other college or department at Virginia Tech.

“I think that it's good for students obviously,” Benning said. “As long as they [those who work in the Division of Campus Planning, Infrastructure, and Facilities] want to keep volunteering their time, I think that’s a wonderful opportunity.

“I think this could encourage other departments, other programs to think about ways that they could do experiential learning. You can even do it with first-year students. They're capable of doing a lot. You just have to sort of mentor and guide and let them kind of run with what you give them.”

Shewchuk learned that she could do a lot. She also found out that real-world learning can be just as rewarding as classroom learning.

“Certainly, [it can] when you get to do something more meaningful like a project like this,” she said. “I was excited to do it.”