English professor's discovery sounds international art alarm

Sweta Baniya's discovery of a sacred Nepali necklace, first posted on her Twitter account, put her smack dab in the middle of an investigation of looted art that still is making headlines.

This isn’t just any necklace.

Friends kept telling Sweta Baniya about the vast collection of Nepali artifacts on display at the Art Institute of Chicago. Baniya, an assistant professor of rhetoric, professional, and technical writing at Virginia Tech and a native of Nepal, wanted to see them for herself.

One item — a 400-year-old necklace made of gilt copper and stones — was of particular interest to her.

But what Baniya saw on June 12, 2021 and posted on her Twitter account sounded an international alarm and placed her smack dab in the middle of an investigation of looted art that still is making headlines.

Last month, ProPublica, an independent nonprofit newsroom, along with Crain’s Business Journal, co-published an investigative account of the institute’s items donated by the late Marilyn Aldsdorf, a benefactor. The art is displayed in the institute’s Alsdorf Collection.

The necklace, which is from the Taleju Temple in Kathmandu, Nepal, and believed to belong to Taleju Bhavani, a revered patron goddess, is one of the primary items of investigation.

It marks the start of Baniya’s story, and one that has a unique connection with her scholarly work at Virginia Tech.

Baniya visited the institute in 2021 with her fiance, now her husband, Carlos Perez-Torres, a collegiate associate professor in the Academy of Integrated Sciences at Virginia Tech. The two spent the day in Chicago to celebrate Carlos’ birthday.

When Baniya rounded a corner in the institute’s Art of Asia section and saw the necklace in its glass case, her emotions took over.

“I was starting to cry and starting to pray, and I just felt like worshiping the goddess herself, “ said Baniya, who is Hindu. “It’s not just a necklace, it’s a part of our goddess who we worship. I felt like it shouldn’t be here. It’s sacred and it’s very famous in Nepal.”

The goddess is known as the chief protective deity of Nepal and its royal family.

In Nepal, the public is allowed to enter the Taleju Temple only once a year during Nawami, which is the 9th day of the Dashain Festival, a Hindu religious celebration. While living in Nepal, Baniya recalled her yearly visits there each October as an adult, where she waited in a long line to walk inside.

“It’s a very special day,” she said.

Baniya took photos and a video of the necklace in its institute exhibit case and posted them to Instagram and Twitter. By the next morning, Baniya’s Twitter feed was blowing up, mostly with accusations that the necklace had been stolen from Nepal and her friends retweeting her photos and video.

Baniya said she did not initially think that the necklace was a stolen piece of art, but she was uncomfortable with how it was displayed at the museum.

“I was very overwhelmed with the emotions I had,” she said. “I had a lot of questions and confusion, and the necklace overwhelmed me.”

Journalists in the United States and in Nepal started contacting her as news of the necklace and other Nepali artifacts gained traction. Also, there has been a swelling response from the Nepali community and activists working on the ground clamoring for the necklace’s return to Nepal.

Through her research, she learned that the necklace was stolen from Nepal more than 45 years ago and auctioned. But it’s not the only Nepali religious art piece in the Aldsdorf Collection that has been under scrutiny. According to the ProPublica and Crain’s report, at least nine items have been investigated and returned to Nepal.

The necklace remains in Chicago. The institute’s public affairs office did not respond to several requests for comment about the future of the necklace there.

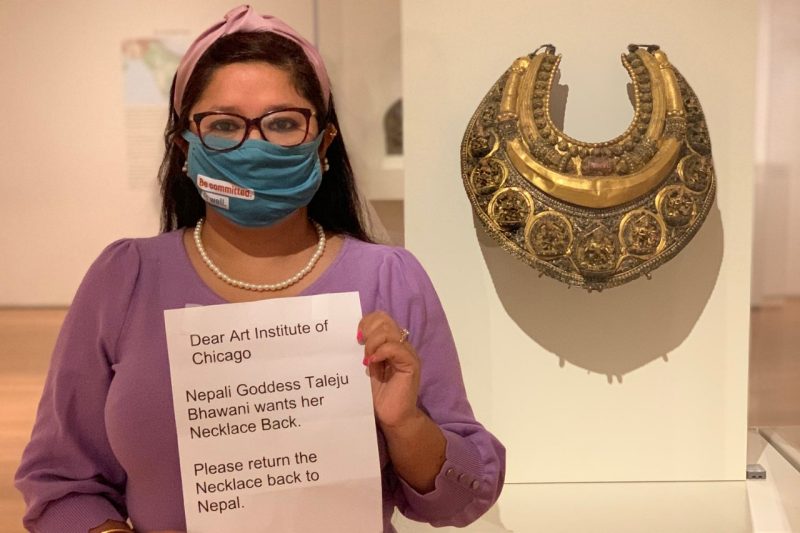

In December 2021, Baniya visited the institute during the winter break, and this time, she stood in front of the necklace exhibit and held a sign demanding that the necklace be returned to Nepal. She also wrote a letter to the institute’s Art of Asia collection director, asking for the return of the necklace to Nepal, where it can be displayed and worshiped appropriately.

Baniya said she did not receive a response from the institute, but she continues to advocate for the necklace’s return on her personal blog and social media accounts.

“They owe an explanation to the Nepali people,” said Baniya, who continues to receive inquiries from journalists around the world. “They are keeping something of our heritage, our religion, and our culture that doesn’t belong to the museum. The necklace belongs to our goddess and should be in her temple.”

At Virginia Tech, Baniya does not talk much about her discovery or the ongoing investigation unless her students ask about it. She said she keeps up with it via news outlets and conversations with family and friends.

The investigation and continued advocacy is a real-life model of some of the concepts that Baniya teaches in her classes at Virginia Tech.

For instance, in her rhetoric in society course for doctoral students, her focus is on advocacy and social justice.

“We teach critical thinking,” Baniya said. “We teach how to ask questions. We teach uncomfortable questions to ask about justice and issues.”

Baniya, who formerly was a journalist in Nepal, said she believes her work in the Department of English and in the humanities area is more important than ever.

“Humanities has a lot of branches, but the world is developing so fast and a lot of times, it’s projected that English or humanities are not that important in the society,” she said. “We are preparing students to be better citizens of this society,” she said. “How do we think about advancing equity? How do we think about issues of climate change, disaster, and everything that we are living in the current world?”

James Dubinsky is founding director of the Department of English’s professional writing program, and he helped to shape the first liberal arts doctoral program at Virginia Tech, including the course that Baniya teaches. The class has been foundational, because it teaches students how to use language to frame issues and move people to support the common good, he said.

“Sweta is dedicated to this kind of work, which is reflected in her focus on advocacy and social justice,” Dubinsky said. “Her focus on and dedication to her home country has become an integral part of her courses, and her students benefit greatly from that kind of international frame.”

Baniya has been part of other work at Virginia Tech to help the international community. Recently, she received an excellence in outreach and international initiatives award from the college. Currently, she is leading a project focused on refugees and immigrants who resettle. Together with Katy Powell, who is director of the Center for Refugee, Migrant, and Displacement Studies, she is working to create a mobile-based application and a website to guide refugees and immigrants through the U.S. citizenship process.

The project is funded by a 2022 digital justice seed grant from the American Council of Learned Societies.

“Our scholarship that we do has an impact and we as humanities or English professors can teach this to a lot of students,” Baniya said.