Researchers emphasize importance of studying rare diseases, which affect 1 in 10 Americans

Rare Disease Day recognizes people living with the challenge of uncommon diagnoses; Virginia Tech scientists are trying to make a difference

On Feb. 28, the top of Wells Fargo Tower in downtown Roanoke will be illuminated with a show of pink, green, purple, and blue. It’s part of an effort to shine a light on important but uncommon diseases in recognition of Rare Disease Day, which takes place annually on the last day of February.

“We all have diagnoses, and we all have disabilities and abilities,” said Stephanie DeLuca, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and co-director of its Neuromotor Research Clinic. DeLuca and co-director Sharon Ramey pioneered the use of a high-intensity therapy that has allowed children with cerebral palsy and other movement disorders to make rapid gains.

They have also applied some of their research to children diagnosed with rare diseases, including CASK disorders. According to the National Institutes of Health, there were just 130 documented cases of the disorder as of 2020. “It’s about being willing to try, and not just assuming that because you have a rare diagnosis that there are not positive changes that can be made,” DeLuca said. “Sometimes it’s that first step that can lead to a lot of learning that can impact many people. It’s one of the things rare diseases can teach us.”

More than 7,000 rare diseases affect 30 million people in the United States, according to the National Institutes of Health. Nearly one in 10 Americans is facing a rare disease.

For most rare genetic conditions, the problem is related to changes in a single gene. Rare diseases share some of the same genetic pathways as more common illnesses, however, so by studying them researchers can develop a better understanding the mechanisms of disease that apply to more common health conditions.

“The benefits of rare disease research stretch far beyond a few affected individuals and their families,” said Michael Friedlander, Virginia Tech’s vice president for health sciences and technology and executive director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute. “Our institute takes a broad approach, coordinating efforts with scientists worldwide.”

Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, a world-renowned geneticist, professor, and director of the research institute’s Center for Neurobiology Research, investigates DiGeorge syndrome, a disorder that occurs when a small part of chromosome 22 is missing. It affects one in 4,000 people.

Researchers in the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute's Center for Vascular and Heart Research study rare diseases that affect electrical signaling in the heart. Fewer than 200,000 Americans are living with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease that can cause sudden cardiac death. Patients with Brugada syndrome usually have mutations in the SCN5A gene, which encodes proteins that regulate sodium channel function in the heart.

Researchers led by Steven Poelzing, a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and co-director of the Virginia Tech Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health Graduate Program, study Brugada syndrome to understand how faulty sodium channels influence cardiac function and heart rhythms.

Nearly one in eight adult cancer patients in the U.S. have a rare form of cancer. They can be challenging to identify, often resulting in delayed diagnosis after symptom onset. Even after diagnosis, treatment options and clinical trials are more limited.

Virginia Tech researchers are targeting glioblastoma, an aggressive form brain cancer with an average survival time of 15 months after diagnosis.

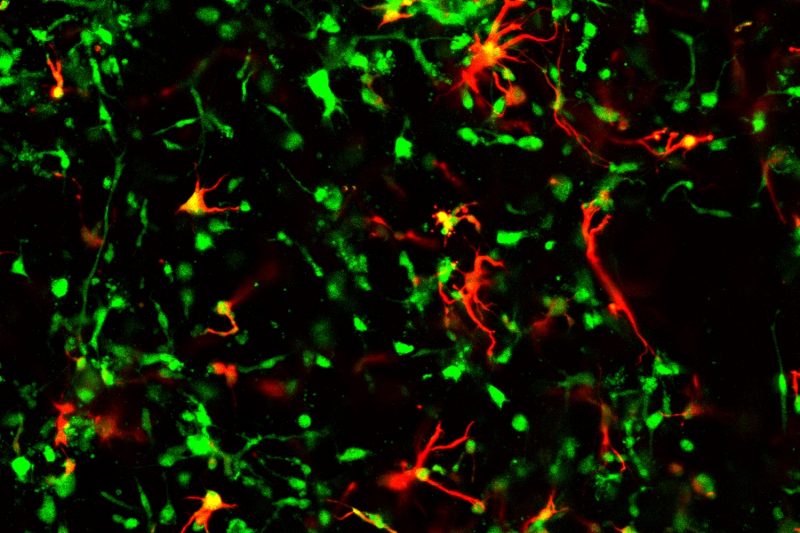

Zhi Sheng and his lab are exploring new therapies for glioblastoma multiforme. Sheng is an assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and a Virginia Tech Cancer Research Alliance member. Samy Lamouille, an assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, was given a Seale Innovation Fund grant to test a novel therapeutic approach to eradicate glioblastoma cancer stem cells. And Associate Professor Jennifer Munson has developed a novel 3D tissue-engineered model of the glioblastoma microenvironment to help learn why the tumors return and how to best eradicate them.

Fewer than 1 percent of children diagnosed with diffuse midline pontine glioma, an aggressive and rare form of pediatric brain cancer, are still alive within five years of diagnosis. Fralin Biomedial Research Institute Assistant Professor Jia-Ray Yu, who last year launched a new laboratory on the Children’s National Research and Innovation Campus in Washington, D.C., is investigating the biology of two enzymes that show promise as targets for combination therapies to treat pediatric brain cancer.

Researchers continue to make progress, but fewer than 500 rare diseases have Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments. Because the number of people affected by any one diagnosis is small, there is little economic incentive to invest the millions of dollars needed for research and clinical trials required to develop effective therapies.

The National Institutes of Health also reports that those with rare conditions experience medical costs three to five times higher than for more common illnesses.

“A rare disease, as defined in the Orphan Drug Act, affects fewer than 200,000 people,” Friedlander said. “But the fundamental scientific discoveries that emerge when we work to understand their cellular and molecular processes provides immense value."

Friedlander also serves on the Virginia Department of Health’s Rare Disease Council, which advises the General Assembly and the Office of the Governor on the needs of individuals with rare diseases. He works with people with rare disease, care providers, researchers, family members, and program leaders to improve prevention, treatment and support services.

“It’s vital that we continue to investigate the mechanisms and treatments of rare diseases to advance our understanding of human health, and help patients with rare diseases while informing new therapies for more common disorders,” Friedlander said.