Virginia Tech team receives $2 million grant to use bubbles to destroy deadly tumors

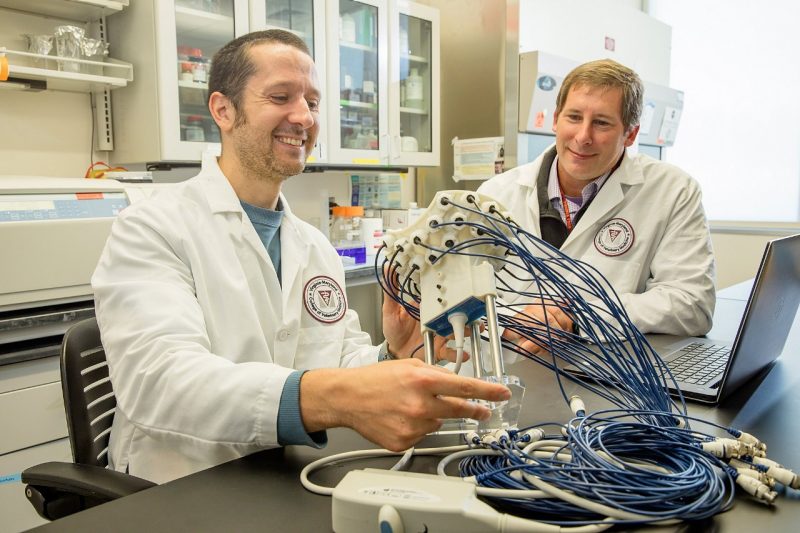

Eli Vlaisavljevich associate professor at the College of Engineering and Irving Coy Allen, associate professor of inflammatory diseases at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. Photo by Andrew Mann for Virginia Tech.

Pancreatic cancer has the highest mortality rate of the major cancers, and only 10 percent of patients live longer than five years after diagnosis. Treatment options can be limited, but an interdisciplinary team led by Irving Coy Allen, associate professor of inflammatory diseases at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, might change that.

The team recently received a $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to explore the use of histotripsy as a therapeutic option for pancreatic cancer.

"This grant is to use histotripsy to treat the pancreas, with the hope that we can also reduce the metastatic lesions as well. We have some great preliminary data showing that it's possible,” said Allen.

Histotripsy uses focused ultrasound beams to generate “microbubbles” in the targeted tissue. The cavitation generated by the bubbles bursting destroys the tumor cells and releases tumor-associated antigens — and antigens are just what the immune system needs to identify and attack the remaining cancer cells, including cells that have metastasized or spread to other sites in the body by metastasis.

The team consists of Allen; Eli Vlaisavljevich of the College of Engineering; Sherrie Clark, professor of theriogenology; Chris Byron, associate professor of large animal surgery; Nick Dervisis, associate professor of medical oncology; Vaidehi Paranjape, assistant professor of anesthesiology; and Kiho Lee of the University of Missouri.

In humans, pancreatic cancer often goes undiagnosed for years due to its unspecific symptoms and the pancreas’ location deep within the body. This means that by the time pancreatic cancer is diagnosed, the cancer has metastasized, creating tumors in other parts of the body.

Most other techniques used to destroy tumors use heat and “cook the tumor,” which damages tissue and can actually inhibit immune system activation, but histotripsy is nonthermal and noninvasive. No surgery is required, which makes multiple treatment sessions more viable. The team believes that killing the cancer cells without heat improves immune system activation.

The team is looking forward to moving beyond pilot studies to answer some of the big questions that still remain including:

- Which tumor-disrupting technique is the best approach for treatment of the tumor?

- What exactly is the immune response to histotripsy?

- What other therapeutic options can partner with histotripsy?

This is a project five years in the making, as the team has worked to gather the preliminary data needed to secure the grant. Over the next five years, the team will study the effects of histotripsy to pave the way for human trials.

Histotripsy is an exciting technology that can be applied to many different cancers, and Virginia Tech is home to several histotripsy research projects.

Joanne Tuohy, assistant professor in the veterinary college’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, is working with Vlaisavljevich to treat canine osteosarcoma with histotripsy at the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center in Roanoke. Vlaisavljevich also is involved in studies using histotripsy to treat liver cancer, which just completed a promising round of human clinical trials, as well as work with Allen on another project using histotripsy to treat uterine fibroids, which was just awarded another $500,000 research grant through the NIH.

“We're applying histotripsy in lots of different ways, drawing from expertise across all departments here at the vet school. Virginia Tech is in a unique position because it has a college of engineering, a veterinary college, and the medical school. These combined resources allow us to conduct cutting edge research from bench to kennel to bedside,” said Allen.

“We hope that this will soon become a possible treatment option for patients suffering from this terrible disease.”

Written by Sarah Boudreau M.F.A. '21