First bats fly through Virginia Tech's new bat cave in Brunei

Virginia Tech Professor Rolf Mueller started a journey to record the movements of bats in Brunei nearly three years ago. Now, having overcome multiple delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, he has a working motion capture tunnel for both live bats and robots that copy their flight.

With an array of high-speed cameras and ultrasonic microphones, the tunnel’s technology captures the motion and biosonar pulses of the flying bats. By observing and recording this information, the researchers will form a more complete picture of what bat flight looks like down to the smallest movement and how sound and motion come together to enable their deft aerial maneuvers.

The plan had always been to build the tunnel in the United States, then disassemble and ship it to the small equatorial country of Brunei, capitalizing on the country’s diverse and abundant bat population. Many moving parts were synchronized to make this happen. This included the completion of a frame design from a senior design team in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and a commitment of funding, facilities, and collaborators from the University of Brunei Darussalam (UBD), the national flagship university of Brunei.

That flight tunnel was originally slated to be deployed in the spring of 2020, but restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic put the research in the dark for a short time. International freight became impossible, and in-person work restrictions meant that the team could do little more than meet virtually. Mueller’s team still found ways to work in this blackout period, just like their winged subjects make hairpin turns as they navigate the night sky.

The senior design team had done some preliminary design on the tunnel prior to the COVID restrictions, and its members continued working remotely to deliver a set of plans that could be assembled as soon as in-person work was possible. The seniors graduated in May 2020; however, Mueller gathered a small team of undergraduate and graduate students to pick up those plans and carry them to fruition.

The tunnel finally shipped out in late 2021 and arrived in Brunei in January 2022. A team of 10 students from the United States followed in late May, funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) International Research Experiences for Students project. Five of the students were from Virginia Tech: three mechanical engineering majors, one majoring in engineering mechanics, and one electrical and computer engineering major. The remaining five came from Brown, Duke, Texas A&M and Virginia State universities, as well asthe University of New York at Buffalo. An additional student from Cornell University arrived in early August.

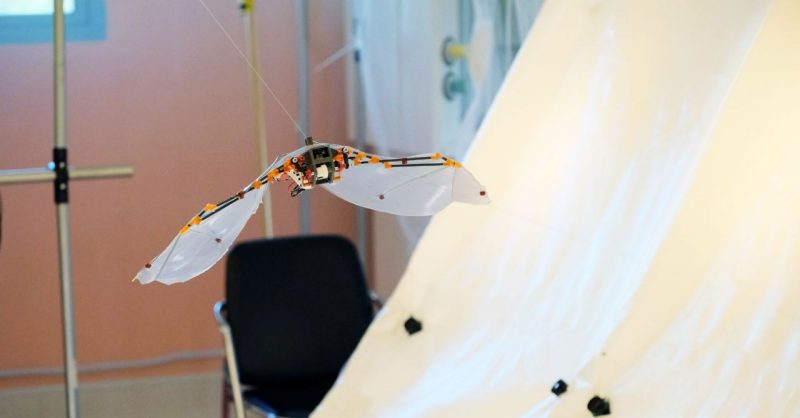

The unanticipated COVID delay gave Mueller some extra time to expand related research. While the tunnel was being constructed in Blacksburg, Mueller mentored two additional teams of students to investigate and model fine movements of a bat’s ears and wings. The students used data from Mueller’s existing research to create one model specifically for the sonar-sensing movement of a bat’s ears, and a second to model the flapping of bat wings. Had the tunnel launched on time, these robotics projects would not have progressed as far as they have. Mueller saw an opportunity to bring the projects together and put the tunnel observations directly into a technology.

“We want to fly the flapping bat robot through the tunnel just like we do for the bats,” said Mueller. “This will give us the opportunity to gauge how far our robot still is from the bats and decide which improvements should be tackled first.”

The tunnel comes online

After a month of settling in and fine-tuning the structure, the team was ready to put the tunnel to work. A celebratory showcase event was held June 29 to mark the official start of research in this joint effort with the UBD. The event included video greetings from Virginia Tech leaders who were unable to make the trip to Brunei, including Guru Ghosh, vice president for Outreach and International Affairs, and Julia M. Ross, the Paul and Dorothea Torgersen Dean of Engineering.

“The bats of Borneo have some of the most sophisticated biosonar and flight systems found in nature,” said Ross via video. “Up to now, no engineered system has come anywhere near the performance of these amazing animals. Learning from these bats will enable new technologies that push the envelope of what man-made autonomous systems can do.”

Jeffrey Barrus, public affairs officer of the U.S. Embassy in Brunei, delivered congratulatory remarks on behalf of Caryn McClelland, the U.S. ambassador to Brunei. The event was attended by the UBD president and several vice presidents, a delegation from the U.S. embassy, directors from four ministries of the Brunei government, as well as representatives from Brunei businesses.

With the celebration behind them, full work days in the lab facility began. On a typical day, the students split into teams. One team develops and maintains the tunnel, preparing hundreds of meters of cabling for the array and fixing any issues that arise. Another team continues to develop the flapping-flight robot and the sonar robot by testing and writing dedicated code to give the robots the commands they need to move. A final team is focused on field work. This team gets to sleep late, but also works well into the night to find and observe bats. Having been extensively trained in the capture of bats, this team brings the animals back to the lab for behavioral observations in the flight tunnel. Eventually, they hope to establish a permanent colony of domesticated bats in the lab.

Early integration of the flapping bat robot into the tunnel was accomplished by attaching the mechanized creature to a zipline so that it could “fly” in a way similar to real bats. While the team hopes to continue development of the robot until its members have a fully functional robot that can sustain its own flight, the focus right now is on the movement of the wings. The team compares this data with the Brunei bats’ flapping motion to form a more complete picture in hopes of recreating the motion.

Team members will continue observations through the middle of August, when they will leave Brunei. After that, the local UBD team together with the Cornell student collaborator will continue the research. Throughout the experience, the students have continuously documented their experiences on the lab’s Twitter feed.

“The work in Brunei gives us the ability to collect detailed quantitative data on bat biosonar, flight, and the integration of the two,” said Mueller. “This gives our work on bioinspired robots in Blacksburg the edge of having firsthand knowledge of how the bats solve problems that are well beyond the state of the art in engineering. Without this input, there would be little hope for any substantial advances beyond the state of the art.”

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)