For undergraduates, research can be a route to self-discovery

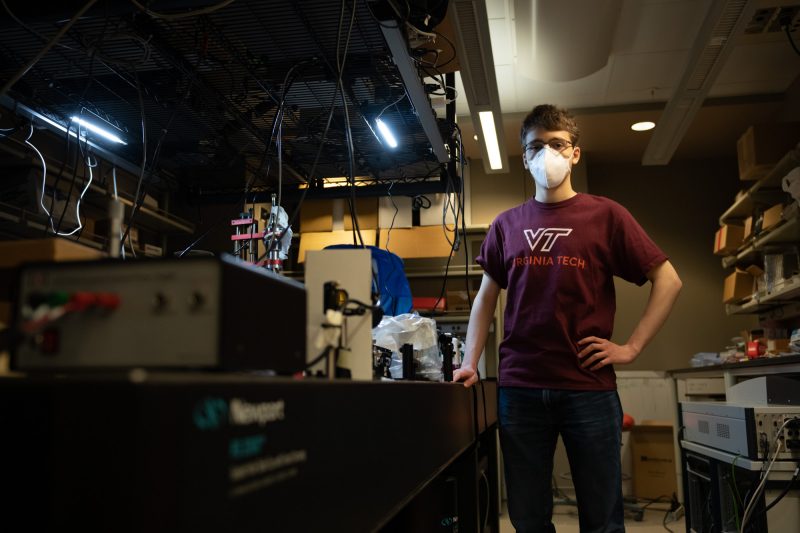

Photo of undergraduate student Yannick Pleimling in a physics lab.

Yannick Pleimling has always liked science. But when he got to physics, he said, “it just clicked. I like the problem-solving structure of physics: Here’s a toolkit, and here’s a problem you can tackle.”

The problems Pleimling — a second-year physics student who’s also juggling a double major in math — is tackling these days are related to the properties of copper perovskites, light-absorbing minerals that could replace toxic, lead-based materials in solar cells and other photovoltaic applications. Every week, he carves out a few hours from a schedule crowded with problem sets and exams to hunker down in a compact lab in the Life Sciences district, using laser systems placed on optical tables with a precise series of mirrors and sensors to study how copper perovskites respond to specific wavelengths of light.

He’ll continue his research this summer with funding from an undergraduate research fellowship from the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science.

The research institute is one of seven at Virginia Tech dedicated to making sure that the university’s researchers get the resources they need to pursue their ideas. That includes researchers whose bachelor's degrees still lie a few years in the future.

The fellowship grew out of a conversation between Mary Kasarda, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and the research institute’s director of scholarship, and Keri Swaby, the director of the Office of Undergraduate Research.

Swaby’s office helps connect students with advisors, funding, presentation opportunities, and all the other pieces that make up a successful research experience. She estimates that they interact with several thousand students each year, at all stages of their college careers — and has seen that students who don’t encounter research until their third or fourth years often wish they’d found it sooner.

That’s why Swaby and Kasarda crafted the ICTAS fellowship to attract first- and second-year students. Students who have already done a semester of research for course credit can use the fellowship to continue their project after the semester is over. The extra funding can convert what might otherwise have been a single line on their transcript into a springboard for the rest of their career.

Giti Khodaparast, a professor of physics in the College of Science and Pleimling’s research advisor, saw the announcement for the fellowship and forwarded it to Pleimling. He jumped at the opportunity to extend his project, which is a collaboration with Lina Quan, an assistant professor of chemistry.

“Yannick is a quick learner and has developed a great sense of teamwork in my diverse research group,” Khodaparast said. “He has been contributing greatly to our collaboration with Professor Quan.”

Pleimling, who is from Luxembourg, already has his sights set on graduate school and knows that racking up substantial research experience as an undergraduate will strengthen his applications for competitive doctoral programs.

For one thing, he appreciates that learning technical skills like operating common equipment and planning and executing experiments now will shorten the learning curve he’ll face as a new graduate student. But he recognizes that the it’s the aptitudes that have nothing to do with experimental setups or physics principles that may be the greatest advantage he gleans from his time in Khodaparast’s group.

“Communication is one of the most critical skills I’ve learned,” he said. “You need to have experience talking with diverse groups and knowing how to communicate ideas effectively. I’ve also been able to understand more of the research process.”

Swaby agrees that students engaged in research are soaking up much more than subject-matter expertise. One benefit, she says, is that research is unpredictable by nature: Navigating that bumpy trajectory helps students build up resilience and teaches them to troubleshoot in real time.

Research also puts students in the position of creating knowledge, rather than just absorbing it. For some students, that switch can reorient their entire perspective.

“Applying what they're learning to solving real problems can be life-changing for a lot of students. Sometimes classwork can be very abstract, but with research you’re dealing with something tangible,” she explained. “It helps students connect to the material and inherently develops this skill set that they can’t really develop in other ways.”

In fact, that’s what happened for Swaby, who was almost ready to drop her college major in chemistry when a summer internship at a bauxite plant rekindled her enthusiasm. “That internship reminded me why I liked chemistry in the first place and just made it more real. It was like connecting the dots.”

She wants every student to have the opportunity to have that kind of clarifying experience, if it's something they want to pursue.

“The biggest thing that I've noticed when I talk to students is that they say, ‘I didn't even know I could do this. I thought this was just for the smart kids or just for the science majors.’ They've excluded themselves. But almost every faculty member on campus is doing research, whether it’s in English or engineering. if you're interested, there are opportunities.”

Pleimling and other members of the research group will present some of their work at the March meeting of the American Physical Society.

“Being able to be an active participant in the physics community is truly the most rewarding thing,” he said. “It feels like you’re contributing to something.”

The ICTAS Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program is open to first- and second-year undergraduate students in any major participating in mentored undergraduate research. One student each year will be selected for the fellowship, which provides a stipend intended to allow students to extend their current research projects with their faculty mentor. The program anticipates accepting the next round of applications in fall 2022, to fund research in spring or summer 2023.