First-ever true millipede with 1,306 legs described by Virginia Tech entomologist

“Millipede” has forever been a misnomer because the creatures never had 1,000 legs — until one was found deep in the Australian desert.

It is not every day that a discovery involving Virginia Tech leads to a rewriting of science textbooks, but a recent find of a millipede burrowed deep under the dusty desert of Western Australia is poised to do just that. Even though the Latin derived millipede moniker (mille “thousand” and pes “foot”) suggests they all have 1,000 legs, one recently described by a Virginia Tech entomologist is the first one ever found to actually have that many.

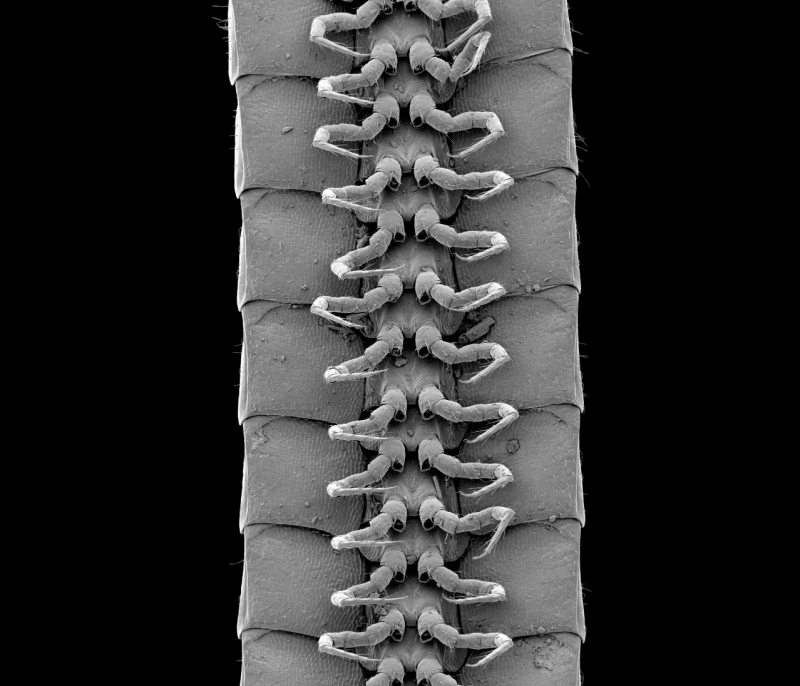

This many-legged subterranean arthropod, Eumillipes persephone, was discovered nearly 200 feet below the arid, rocky, Goldfields-Esperance region in Western Australia. The millipede is described as being colorless, eyeless, and less than half an inch wide. Though the males of the species were discovered with as many as 818 legs, a female specimen walked all over that record with an incredible 1,306 legs. Living so deep under the surface scientists can only speculate what this creature does day to day in all that darkness, but it likely spends most of its time eating fungus.

“We're finding that many new millipede species are living in the deep soil which is a microhabitat that was previously believed to be devoid of life,” said Paul Marek, an associate professor in the Department of Entomology in the Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, who led the team who described and named this record-breaking critter. “This is also a system that we heavily rely on for screening of environmental toxins and also filtering our water. We're finding this to be very much the same case even here in Virginia.”

Prior to the discovery of E. persephone, a California millipede, Illacme plenipes, held the record at 750 legs. Now those begrudgingly written statements clarifying the ‘millipede’ misnomer can be stricken from science textbooks worldwide.

Eumillipes persephone was discovered as part of a biodiversity survey performed alongside mineral exploration. The Goldfields-Esperance region is resource-rich, but a tough location for most animals to survive. With no rivers, sandy soil, and salt-rich groundwater, the region is inhospitable and apparently infertile. None the less, life exists even in these more extreme environments.

While mining companies were scouting for minerals deep below the surface using boreholes, surveyors employed by the companies to conduct mandated surveys used traps baited with decomposing leaves which are placed at different depths within the hole. These biological surveys are used to learn if mining activity in the area may impact any life below the surface. Bruno Buzatto who works at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia found this incredible millipede and immediately contacted Paul Marek.

While excited for the novelty of finally discovering a true millipede, Marek’s research also focuses on what millipedes tell us about evolution, the environment they live in, and what that might mean for us. This crucial work has taken him all around the globe, from the Pacific-Asian region to the East Coast of the United States and many places in between. He is looking for new millipede species, but also examining where they live, what they eat, and how they survive.

Last year he discovered a new species at Virginia Tech’s Duck Pond and named it Nannaria hokie.

“By studying the millipedes, invertebrates, and other animals that depend on and live in these cryptic ecosystems, we can make informed decisions to conserve biodiversity on this planet and also help preserve the environment that humans also depend on,” Marek said.

This research was funded in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation. Katharina Dittmar is a program director for NSF’s Directorate for Biological Sciences and she is the cognizant program officer on the grant used to fund this work.

“Cataloguing and describing the world’s biodiversity can help shine a light on how life on Earth has evolved and adapted,” Dittmar she said. “The discovery of a new species of millipede – the first true millipede – provides us with new information on how organisms live, move, and feed in soil habitats and expands the list of organisms found in the resource-rich Goldfields-Esperance region.”

This discovery just scratches the surface of what subterranean biodiversity can help us learn about the natural world, and what preserving it can mean. The U.S. Geological Survey notes that almost half the drinking water the United States relies on comes from groundwater sources and even more is needed for agriculture. Understanding the biodiversity in these important habitats will help us understand how above ground factors may impact our environment deep below the surface.

“Mining activities and other habitat destruction encroach upon this habitat, making conservation efforts immediately important,” Marek said.

This discovery has inspired Marek and his lab to use subterranean bore holes as a method for investigating local biodiversity in Virginia. The work of the Marek lab has long focused on biodiversity and genetic classification within arthropod and millipede populations.

Jackson Means, who graduated with his Ph.D. in Marek’s lab, was primarily responsible for the hands-on genetic work with E. persephone. He extracted the DNA from E. persephone specimens and prepared them to have their genomes sequenced. Scientists use genetic sequencing to better understand the evolutionary biology of organisms, and to figure out where they come from.

Discoveries like this prompt academic interest, but also these redefining and record-breaking creatures bring excitement and wonder to all levels of the scientific community.

“This discovery reminds us that there are still so many mysteries waiting to be uncovered in the natural world,” said Means. “Who knows what other bizarre and unique creatures can be found in the overlooked corners of our planet.”

And at the heart of it, that is what these types of scientific studies bring to the foreground: that discovery and exploration expand what we know, help us keep our planet (and us) healthy, and rewrite a few textbooks along the way.

.jpg.transform/m-medium/image.jpg)